A Tendency Toward Dirty Laundry: Camille Billops and James Hatch’s Unflinchingly Personal Cinema

In an interview with bell hooks published in 1996, Camille Billops responded to a question about the transgressive candor of her films by saying “It is probably exhibitionism on my part [. . .] some people say our films have a tendency toward dirty laundry. The films say it like it is, rather than how people want it to be.” Billops’s artistic signature was one of temperament rather than form; she was at various turns a sculptor, printmaker, archivist, writer, cultural archeologist, teacher, ceramicist, actor, and family documentarian. Even as she navigated a dazzling multitude of mediums, what remained consistent in her work was an adamant defiance of what might be called a politics of respectability. Billops refused to sanitize or discipline herself and her cinematic subjects by confining them to the narrow margins of what was deemed acceptable. This nonjudgmental generosity is most visible in the films she codirected and coproduced with her husband and lifetime collaborator, theater historian James Hatch.

Billops and Hatch’s extensive intellectual and artistic partnership began in California, where they met in 1959. Born in Los Angeles, where her family had moved during the Great Migration, Billops attended Los Angeles City College and USC’s art school, while Hatch taught theater arts at UCLA. Their meeting catalyzed the beginning of Billops’s professional artistic pursuits. After Hatch’s Fulbright fellowship took them both to Egypt, she had her first solo exhibition in 1962 at Gallerie Akhenaton in Cairo. They subsequently also lived and pursued various artistic projects in India, Taiwan, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. By the time they settled in New York and formally started the monumental archival work that would become the Hatch-Billops Collection—an exceptional trove of African American culture—they had already begun to accumulate a store of shared creative material.

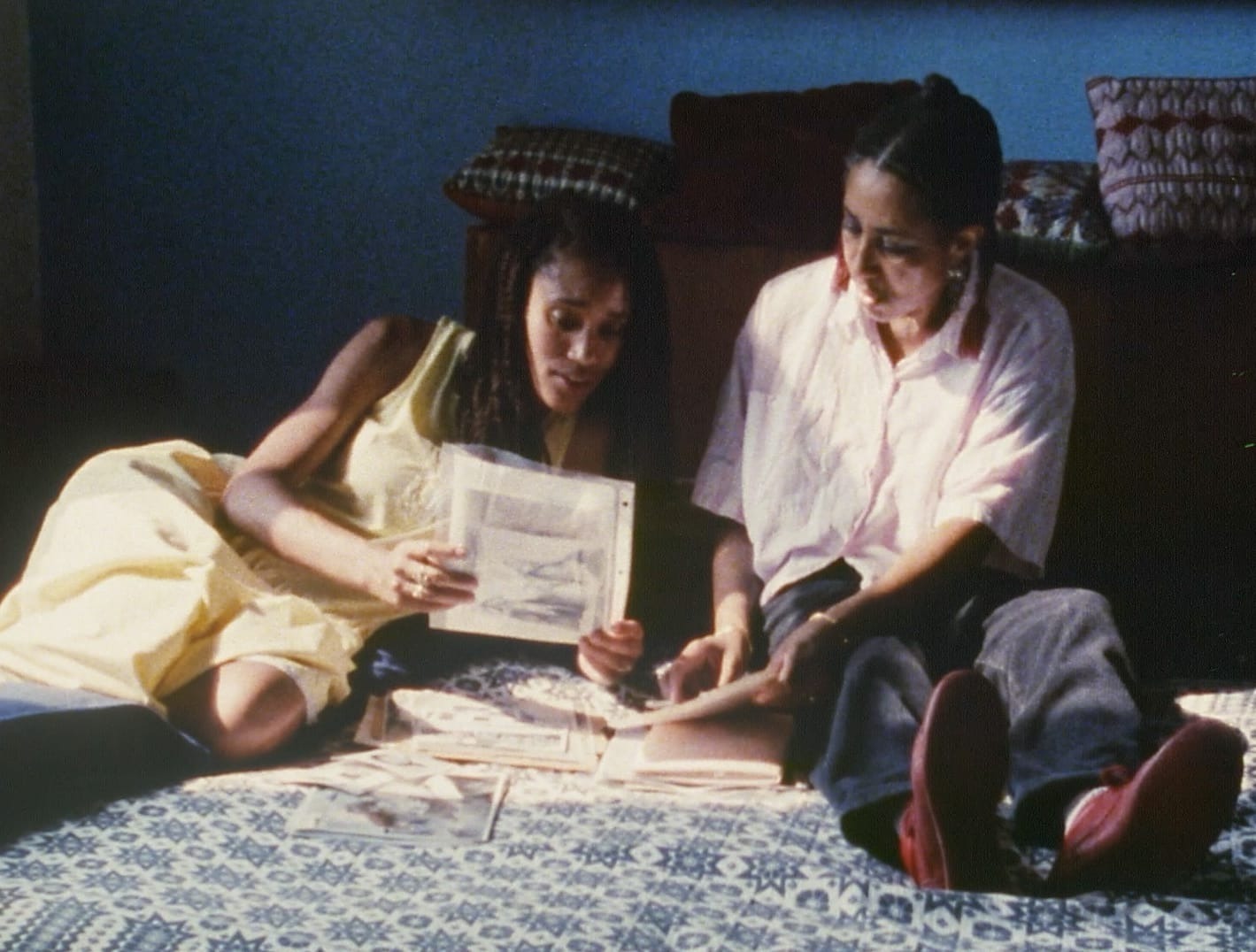

After these travels, they shifted their collaborative energies toward film. The experimental documentaries that they created together defy categorization, freely amalgamating confessional family portraits, keenly observed cultural and social analysis, and a striking element of theatricality. While their work has affinities with that of such New York–based Black artists as Kathleen Collins, who similarly focused on the prismatic multitude of Black women’s ordinary lives, and William Greaves, another virtuoso of unconventional nonfiction filmmaking, its texture and methods are all its own. The films’ consistent edge of operatic zest and whimsy grew out of Hatch’s professional dedication to theater, as well as the couple’s earlier collaborations staging plays during their travels and in New York. Billops described their process as a kind of narrative and creative relay: “Jim and I talk back and forth. We keep telling each other the story, until we come up with something.”

Her impulse toward recording and storytelling was informed by her mother and stepfather’s home-movie habit, and she integrated much of this footage into her work with Hatch. Filmmaking was a family affair for the couple, who named their company Mom and Pop Productions and recruited Hatch’s son from his previous marriage, Dion Hatch, as a cameraman. Three of their films, sometimes referred to as their Family Trilogy, center on Billops’s relatives, using the documentary form on a personal scale to confront topics such as domestic violence and adoption, which were then rarely openly discussed in the public arena. While Billops and Hatch were evidently a collaborative pair, it was she and her family who played out the unblushing confrontations of their films, and whose ethics and flair furnished their drama.