RELATED ARTICLE

Chris Marker: Memory’s Apostle

The Criterion Collection

In Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983), often considered the essay film, we meet the wildcat video game designer Hayao Yamaneko, who imports scenes from his life into his memory machine. The machine is shown only in parts: a slider being pushed, a switch being flipped, a knob being turned, and his screen, which presents memories as clips of stray cats and takenoko dancers and salarymen rushing past. The footage pulsates together as purple then green then orange globules flickering in and out. The narrator, who talks of Yamaneko displaying the memories “like insects that would have flown beyond time,” looks at this contraption with envy. Why must he instead live in a film trapped in dreary, linear time? Why must he endure the stifling structure of a beginning, middle, and end?

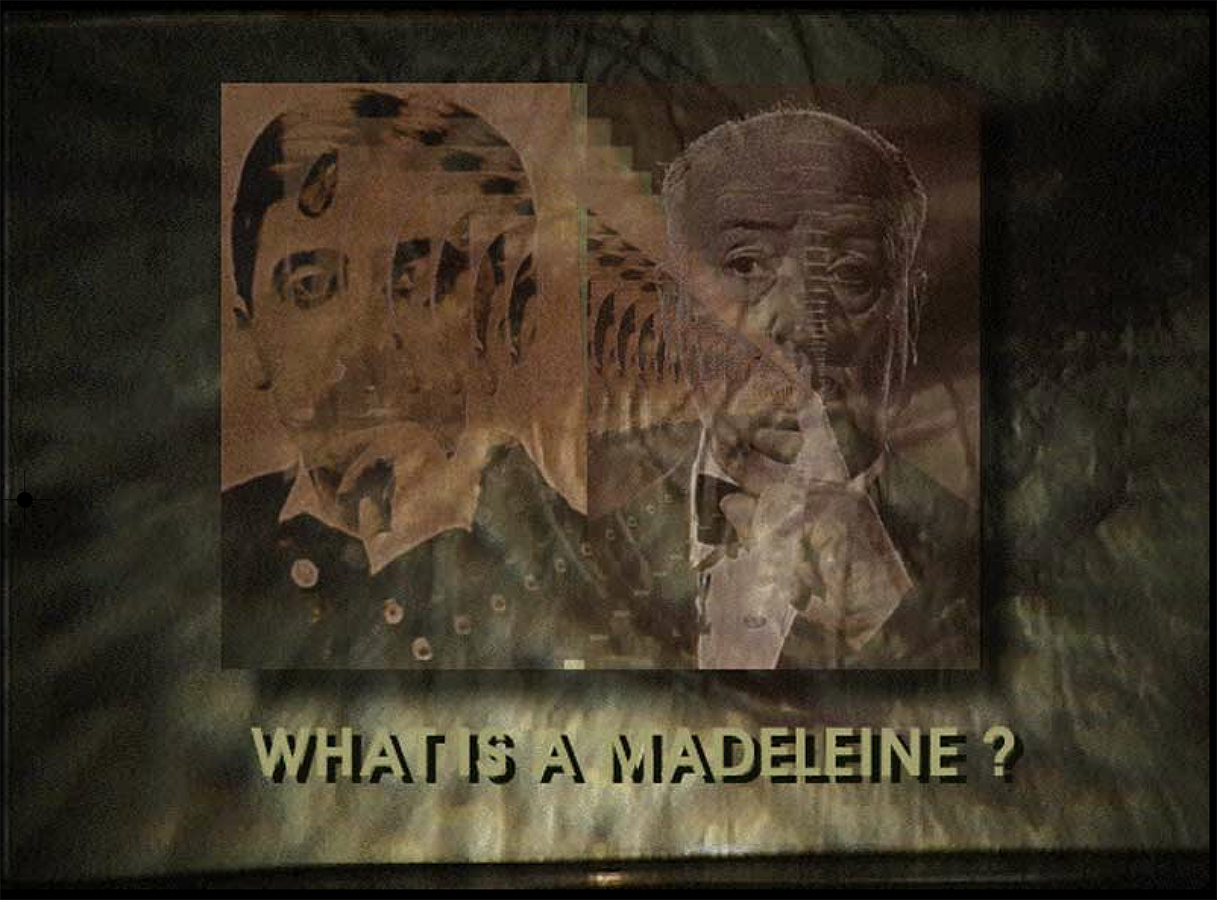

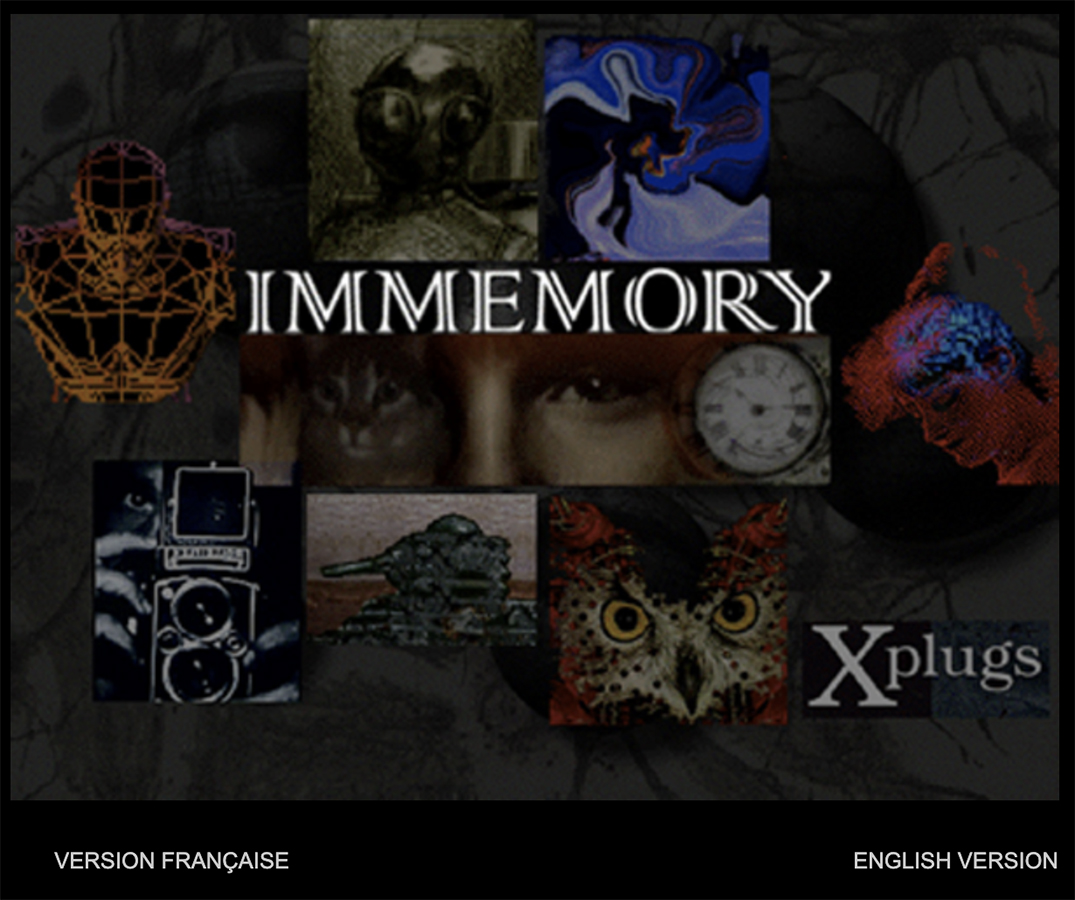

These seem to be the complaints of Marker himself, for in 1997, in a bold attempt to burst through the confines of linear time, he brought the spirit of Yamaneko’s machine to life in a CD-ROM he called Immemory. Not quite a memoir, not quite a game, Immemory is almost a life itself, a sifting through a box filled with his postcards, family albums, movie posters, beloved books, and of course countless photographs—stuff he imbues with meaning and love. Like Proust’s madeleine, or Hitchcock’s Madeleine, Immemory will thrust you out of time and into “the endless edifice of recollection.” Marker’s madeleine becomes your madeleine.

Alongside filmmakers like Agnès Varda and Alain Resnais, Marker has been described as part of the “Left Bank New Wave,” a group defined partially by its left-wing politics and partially by frequent collaborations among its members, but maybe even more by its defiance of categories. How does one categorize Marker? He made dozens of films, but he also produced photo books, articles of journalism, travelogues, novels, an AI chatbot, a Second Life island, and this CD-ROM. What remains throughout his work across formats, though, is his fascination with memory: how we attempt to capture it, and how it can burst forth before us. To begin to approach Chris Marker is to perpetually scratch at an ever-expanding surface, and Immemory is a pretty good place to start scratching.

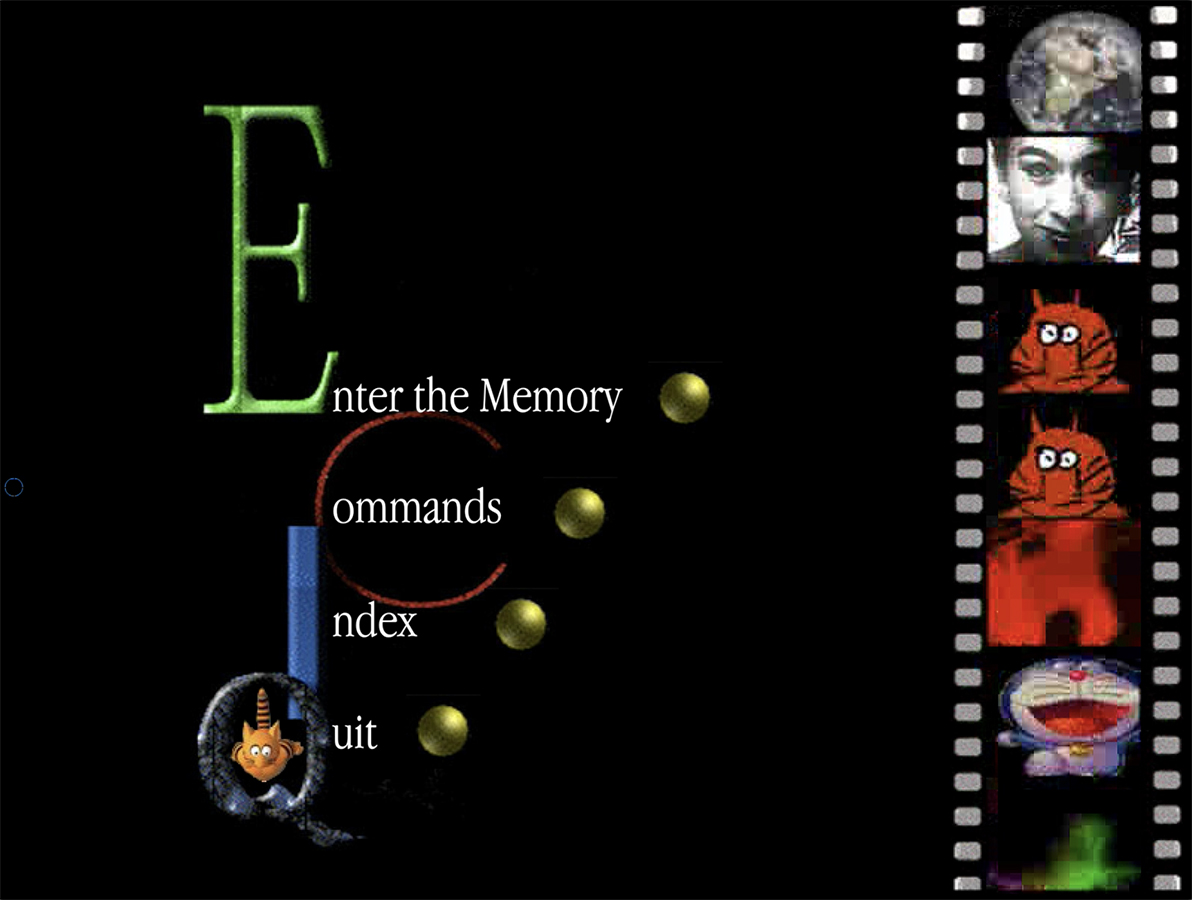

In the opening image of the program, you’re met with the words “Enter the Memory.” Click, and you will find a massive planet containing eight continents Marker calls “zones”: Cinema, War, Memory, Photography, Poetry, Travel, Museum, and X-Plugs. These basic categories hide its overwhelmingly interwoven terrain. Of course, this planet is finite; as a technology, the CD-ROM could infamously hold only so much data, straining even to contain grainy, seconds-long videos. Even when it was still fresh-faced in 1994, the frustrated historian Michael Punt diagnosed the CD-ROM with “hyperbole fatigue,” giving the format only a few more years to live, finding its limitations suitable only for children’s games. So with a kind of inhuman determination and focus, one could probably tour all of Marker’s zones in about four hours, like this one deft YouTube user has.

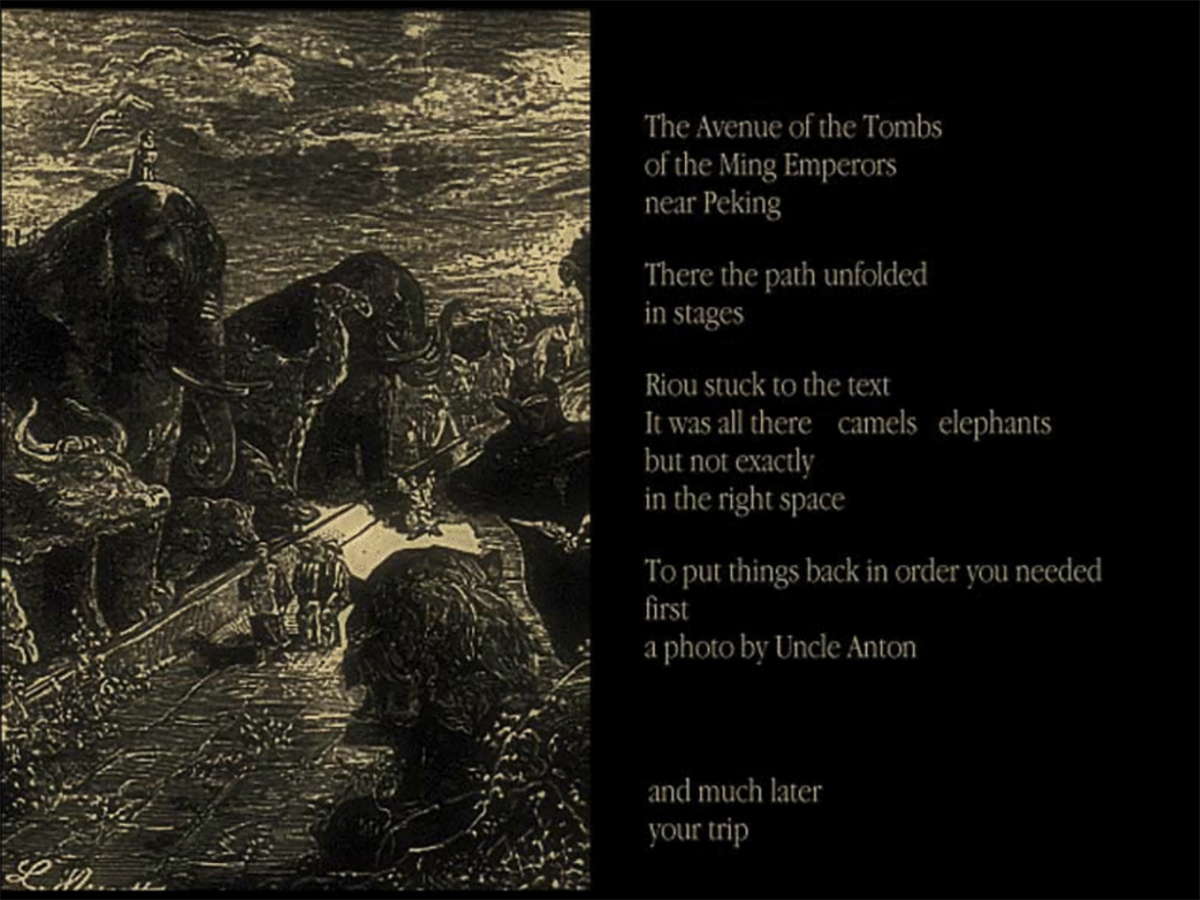

But listen to Marker, or, rather, his charming cat avatar Guillaume-en-Egypte, who insists, “Don’t zap, take your time.” Trace the contours of the artist’s photographs, many softened with a digital vaseline glow, and the pupil of an owl’s eye may fade in to offer a worthy digression. Hover over the right word in a sentence, and a secret alleyway appears. Hopping through these associations from zone to zone only unfurls more branches and surprises for the intrepid explorer to follow.

These branches can sometimes feel more like fissures. Answer the intervening Guillaume, who pops up and asks “WANNA KNOW MORE?” and plummet down into the middle of a paragraph belonging to a completely unfamiliar territory. Another stray click hurls you back into some already well-trodden loop. I kept finding myself winding back again and again to a volcanic isle in Iceland and its modest puff of smoke, which bobs off the screen. But there are no missteps. However precariously you move through Immemory, a structure will form from what Marker calls “the disorder of rhymes, waves, shocks, all the bumpers of memory, its meteors and undertows.” What is at first disorienting quickly becomes exhilarating: the eruption of involuntary memory, right before one’s eyes!

Images from Immemory