Plymptopia

It’s not impossible to be a lazy, shrug-it-off filmmaker, just as it isn’t to be a lazy painter or novelist, or, more to the point, a lazy comic artist, drawing each picture merely once and then moving on. (You could be David Lynch and draw your whole comic strip—“The Angriest Dog in the World”—only once, and phone in weekly captions for nine years.)

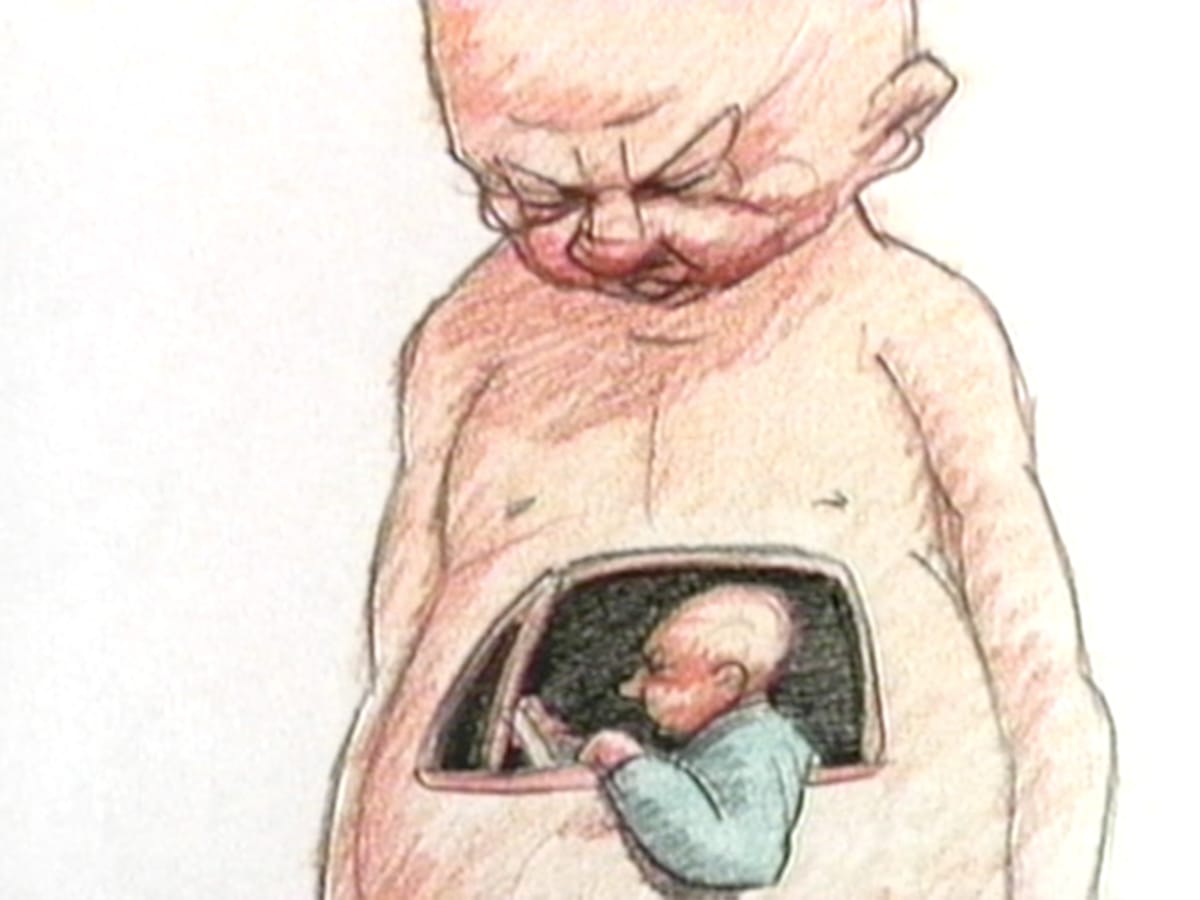

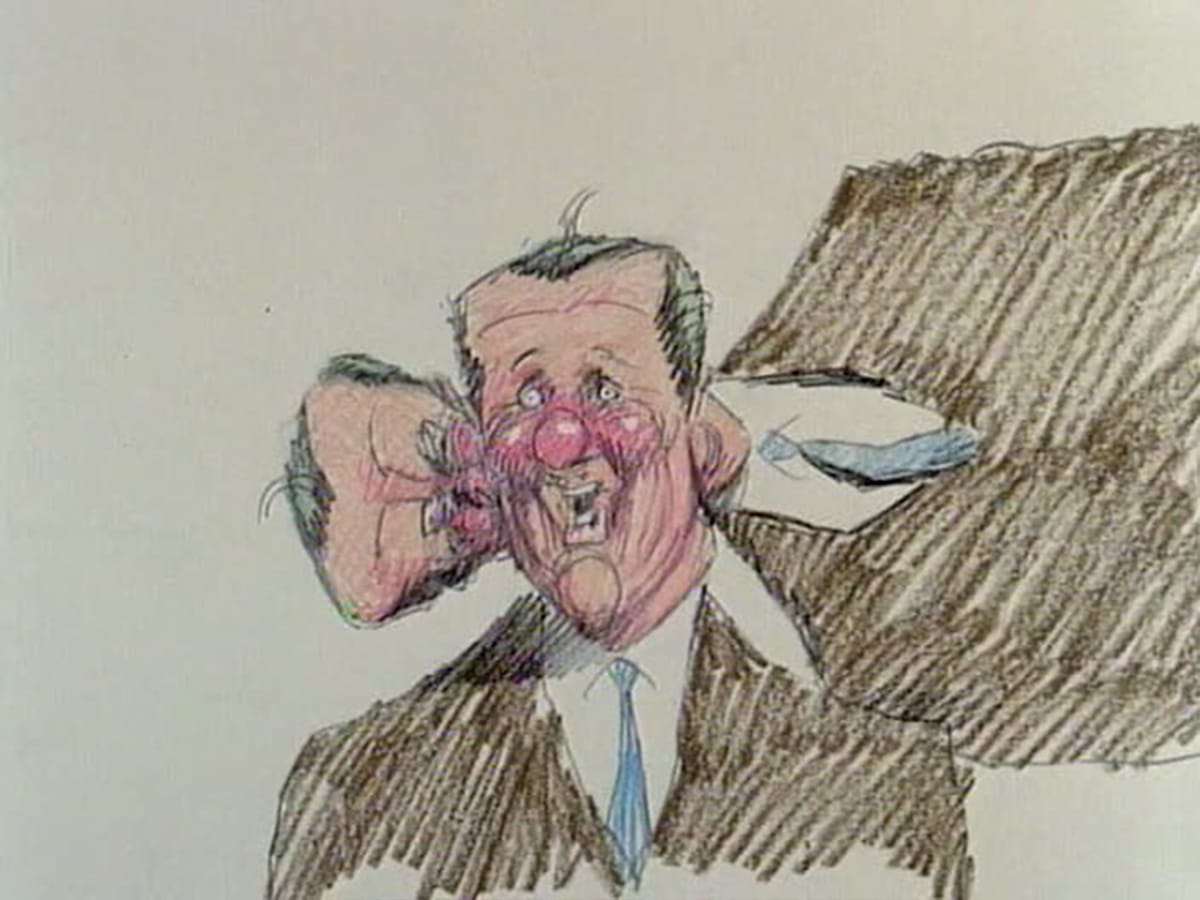

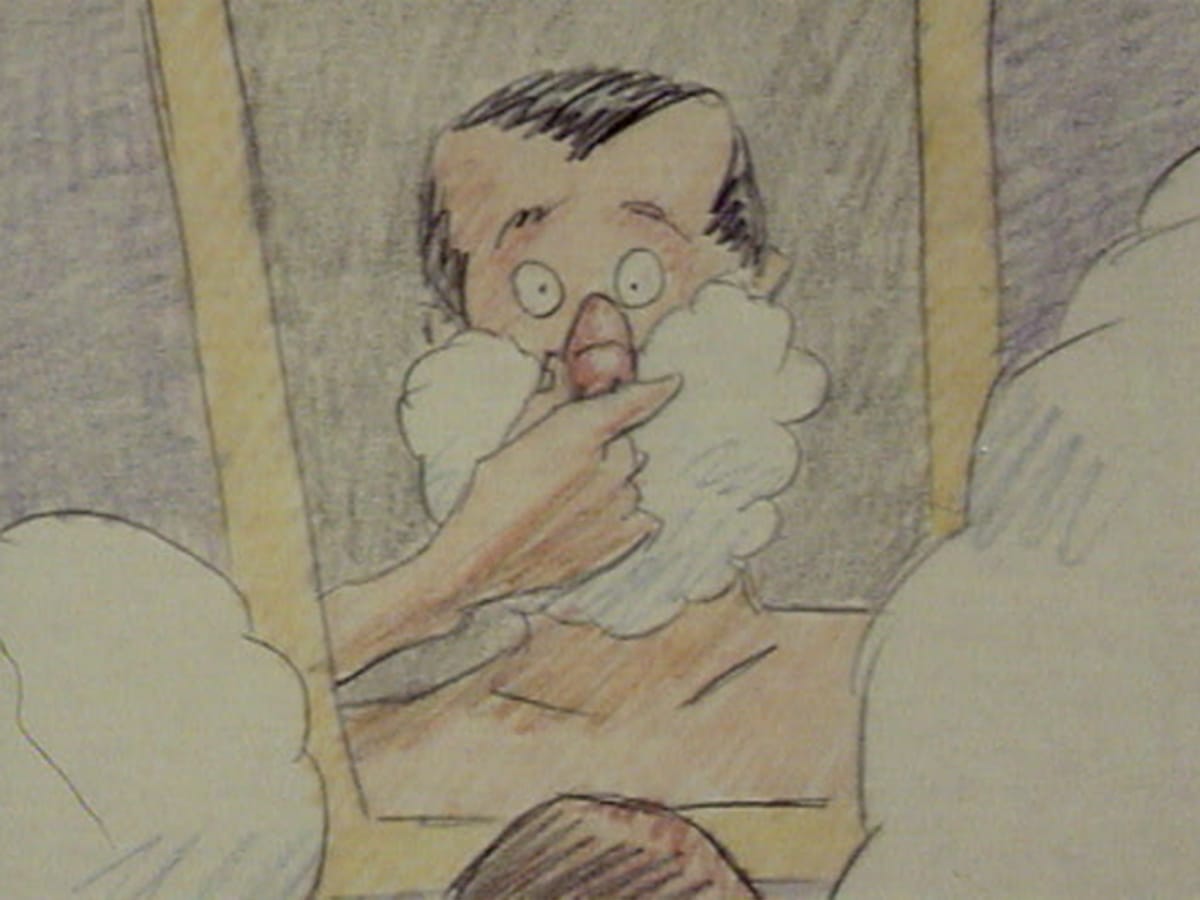

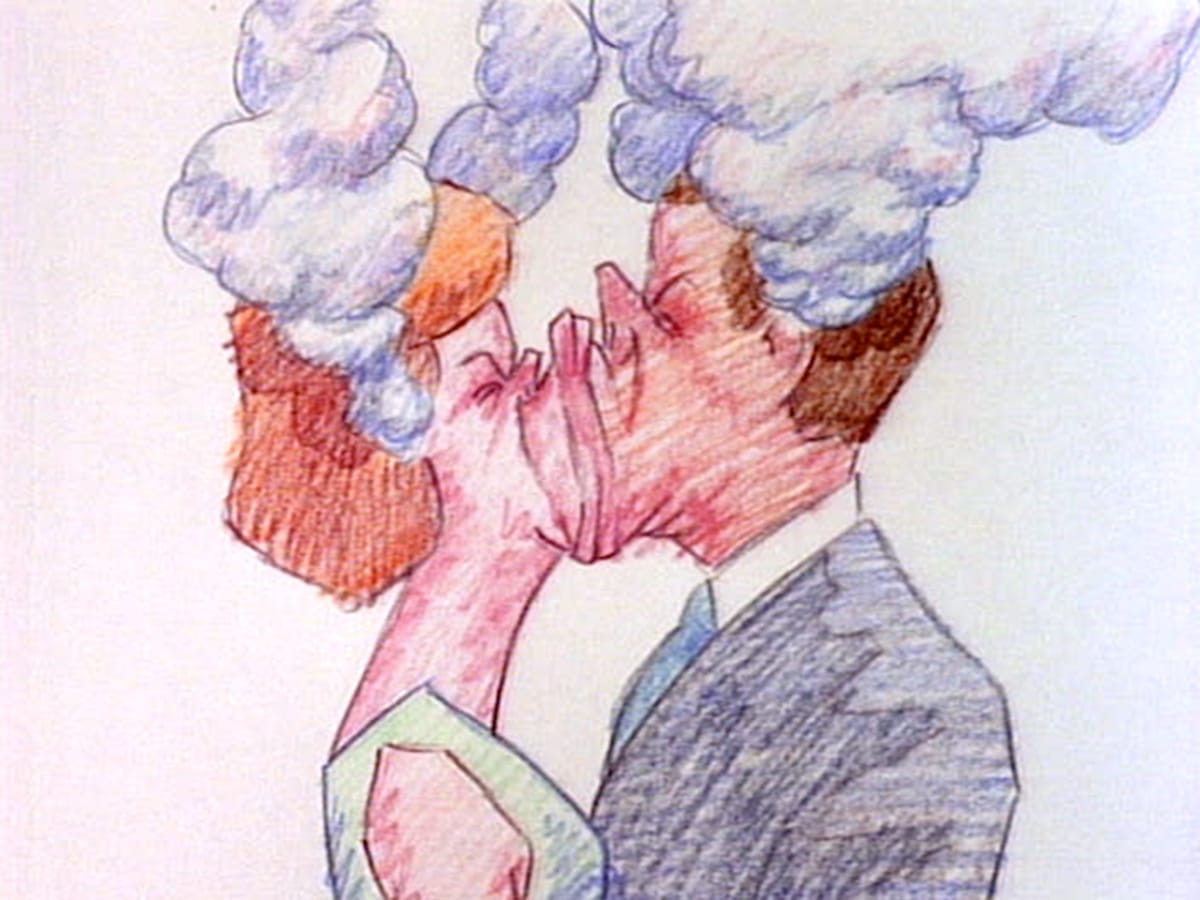

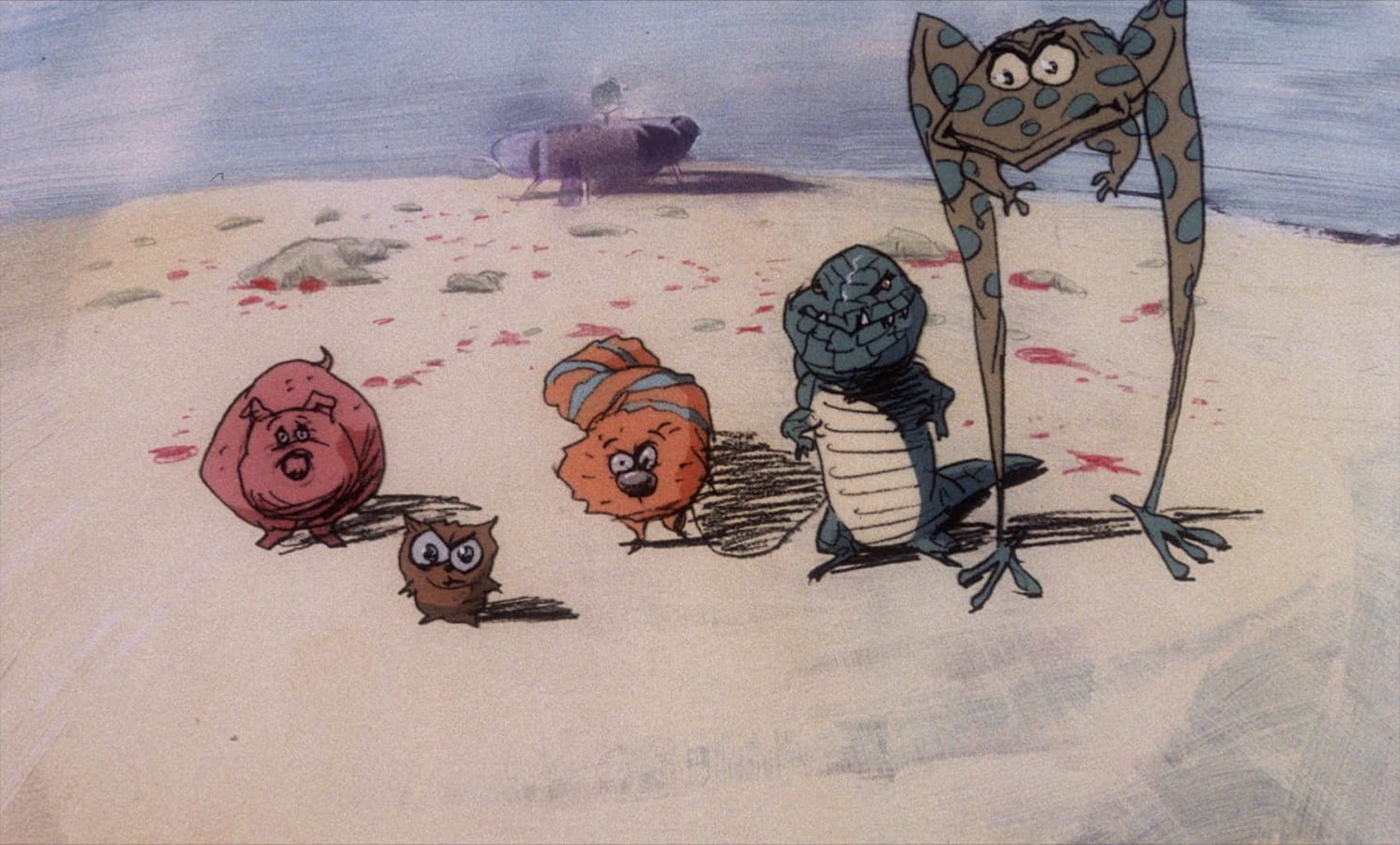

But it is virtually by definition impossible to be a lazy animator, mustering and capturing one frame at a time—by hand!—seemingly for all eternity. It’s a vocation that requires extra-human obsession and stamina, and an anchorite’s lust for cruel solitude. We know this as viewers—it’s part of the mode’s freakish traction, the sense of watching a compulsive build a cathedral one spoonful of mortar at a time while we simultaneously enjoy the finished experience at our own zippy speed, happily uninvolved with the ridiculous, time-devouring labor that went into it. Within this school of lonesome maniacs—which I suppose can include the hordes of unsung digital wonkers working at Disney/Pixar, huddled over their keyboards and arranging pixels for tens of thousands of hours—Bill Plympton is something like the bullgoose obsessive, working completely by himself (on the visuals at least), and often crafting his films with nothing more than colored pencils. (That includes seven features, as many as one person has ever drawn alone.) Watching them, you’re on your own with the filmmaker at his drawing table. The assault of analog-ness is integral to the spectacle of Plymptoons, but of course they hardly feel laborious—it is their defining grace that they veer and whizz and splat and spew like a water balloon fight. It helps that Plympton is one of the best and most distinctive craftsperson-cartoonists since Maurice Sendak, Basil Wolverton, and Robert Crumb, and that his imagination runs toward the childishly anarchic, but there’s something particularly hypnotic and guileless about all those pencil lines, all that sketching, all those millions of desk hours aggregating, magically, into a few moments of abrupt, careening nonsense.

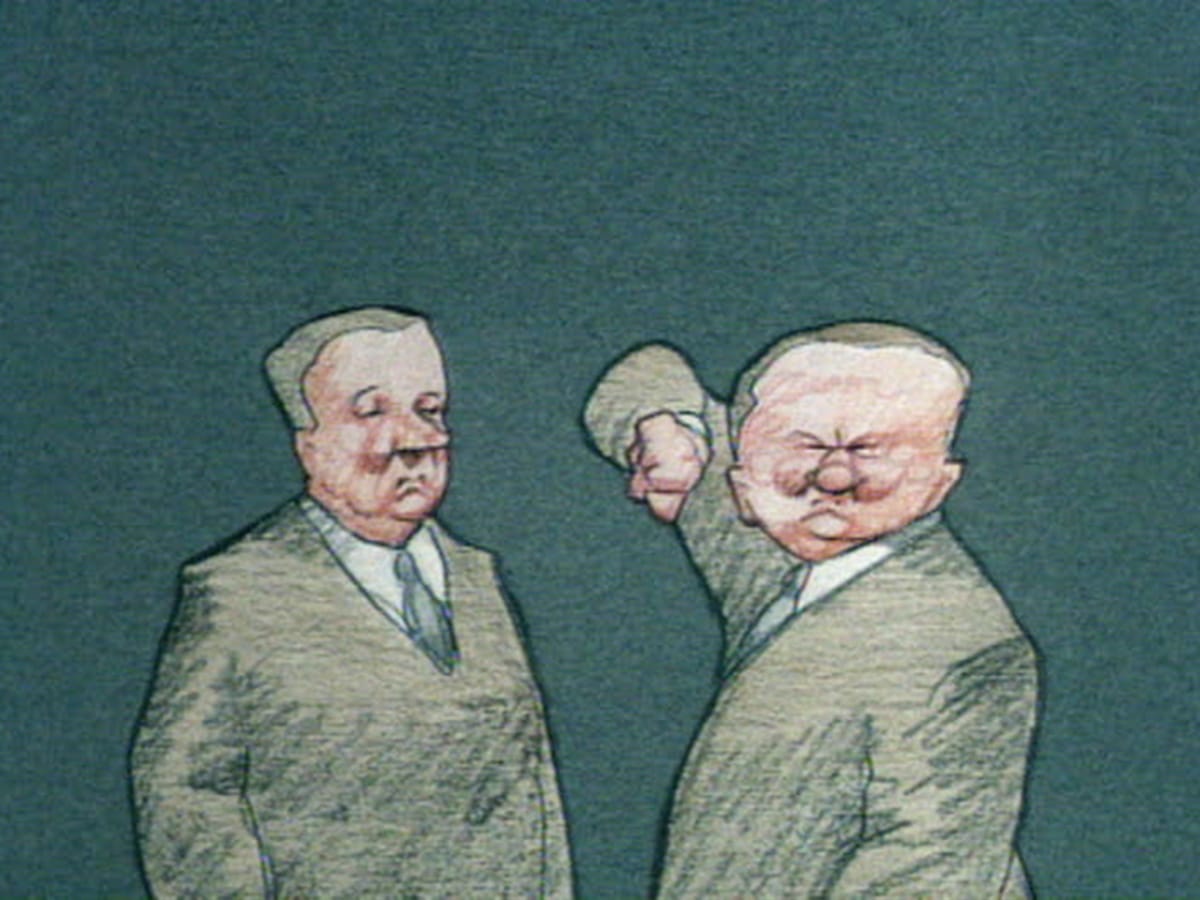

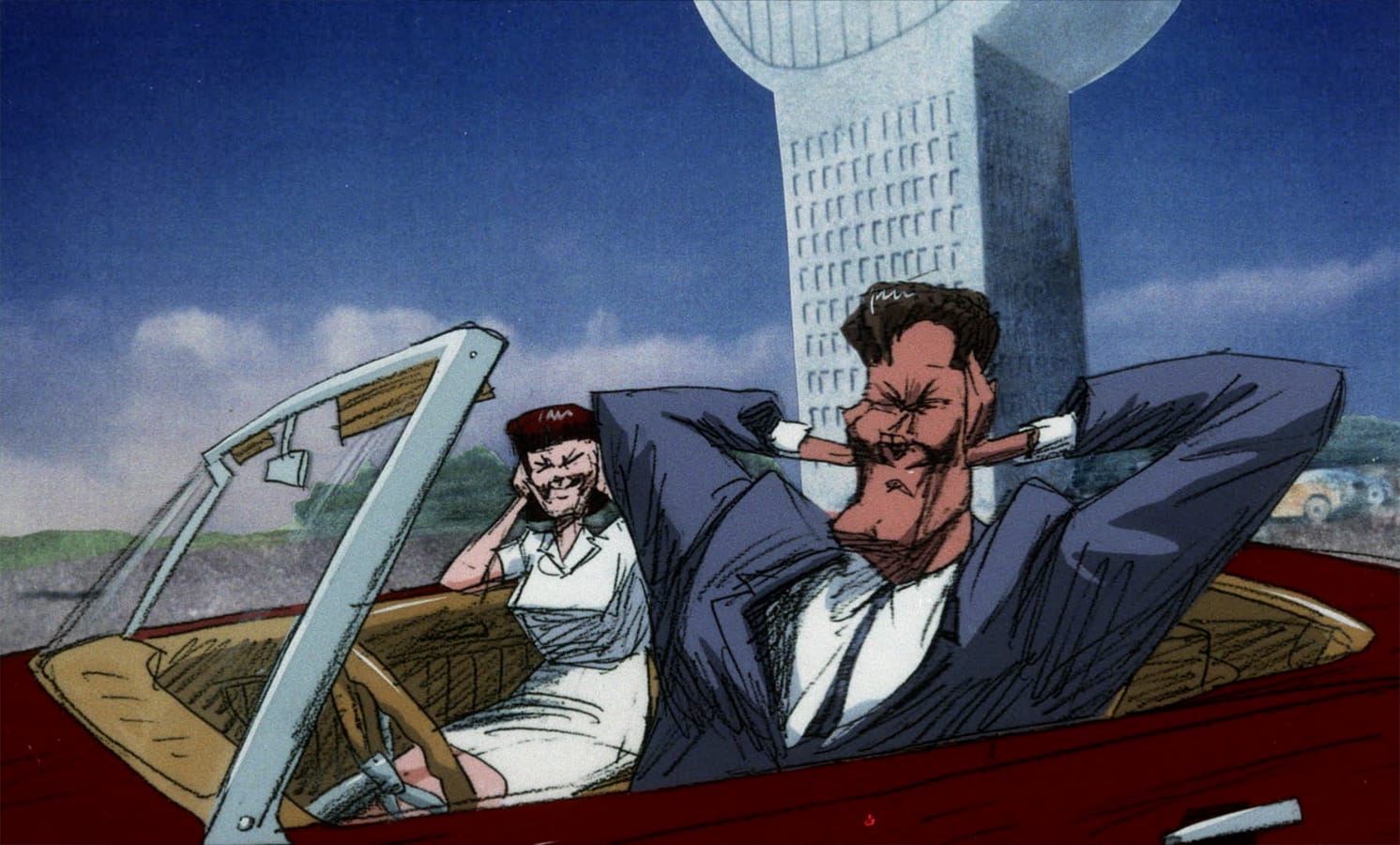

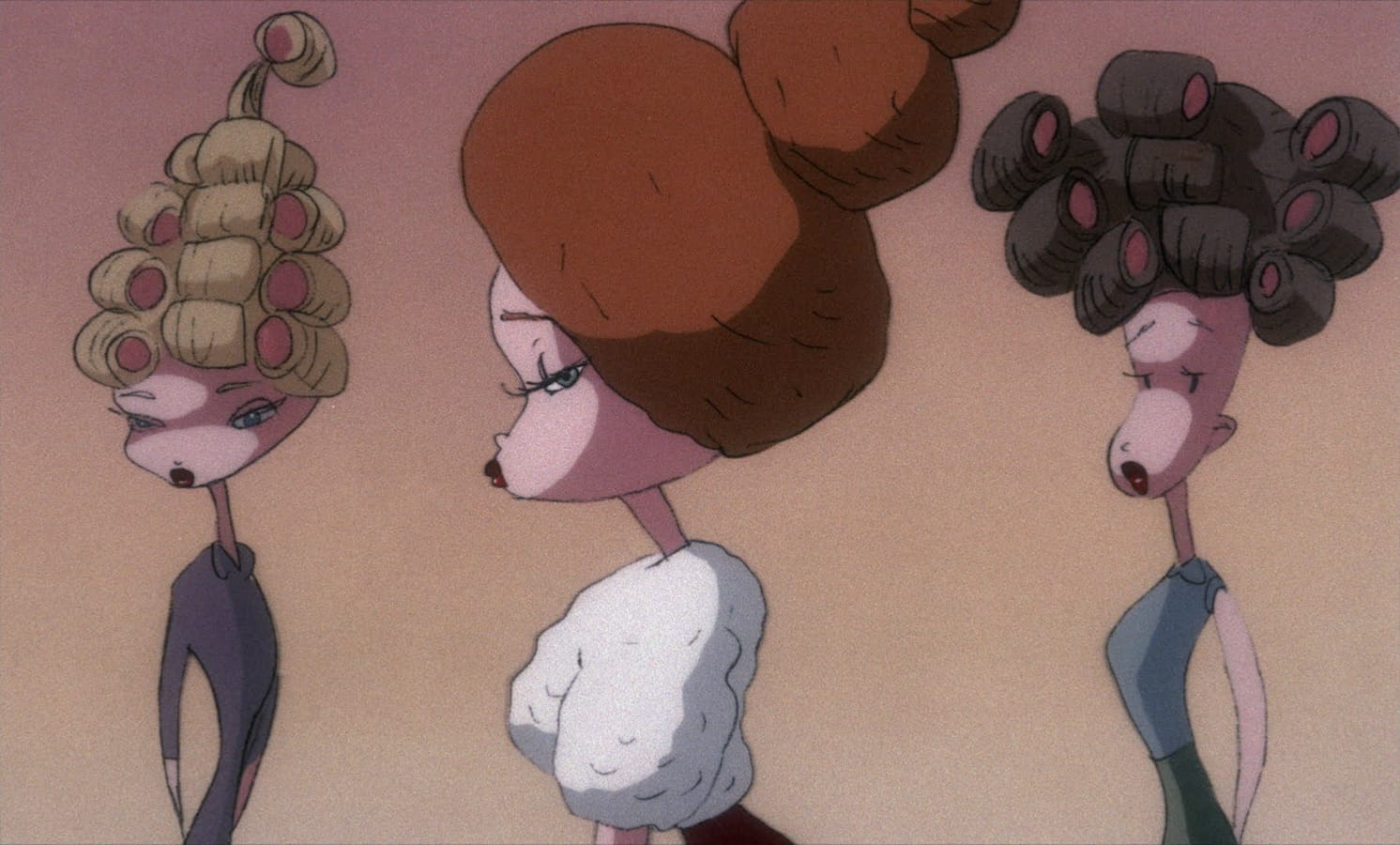

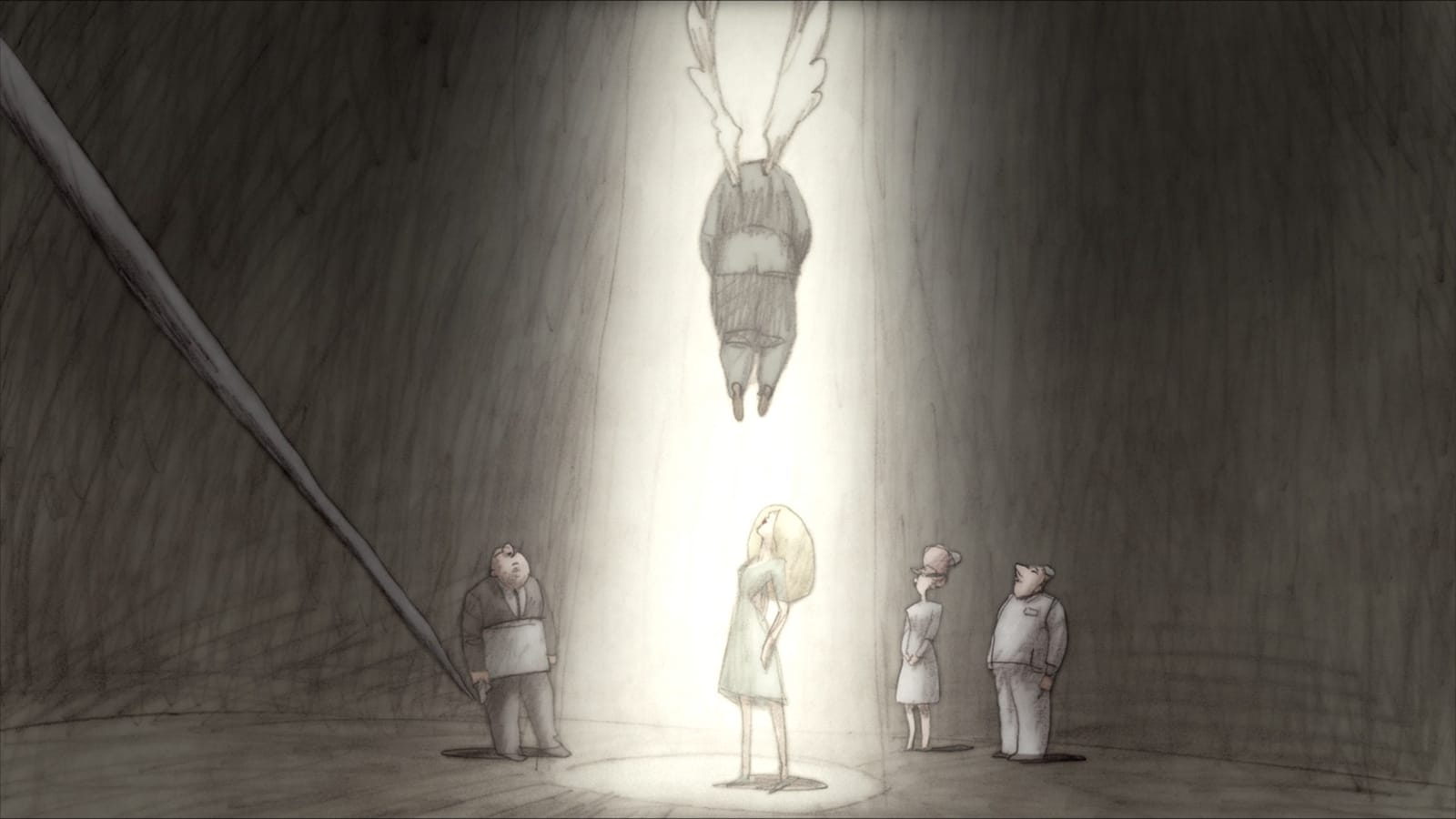

Fast, dirty, and always low-budget, Plympton’s films are not animated “on the ones,” like high-priced animations (meaning, one drawing per photographed frame). His films often shake and shudder on the threes or fours or more, giving the action an anxious vibrato. Even when they discover stability, the world of Plympton’s films is immediately recognizable as his, and his impulsive tropes are a substantial factor in its charm. Everything is mutable in Plymptopia, but nothing is quite as mutable as the human head, which suffers every affront imaginable by humankind, and dozens more besides. Bodies, pets, houses, cars, and appliances are as pliable as taffy. Cascades of disaster and often outrageous gore spill forth with ballistic speed—when they’re not caught in a shivery pregnant pause. (Plympton owns the comic timing that lets his pulsing lines seem to think about what’s going on—or what catastrophe will come next.) The landscape is pure generic American suburbia: blaring sun, treeless lawns, bland ranch houses, endless two-lane blacktop—all of it so flat that it’s drawn to curve with the Earth, aping an ultra-wide camera lens, a move that often extrapolates out to distort interiors so that living rooms and saloons have parabolic ceilings half a mile high. All the better in which to launch a rocket, or be launched by an explosion, or otherwise burst the limitations on perspective and scale because why not. Though he didn’t start animating seriously until the ’80s, the iconography in his films seems tied to the early ’60s, for the most part, if the time-stalled fashions, jukebox rockabilly, tail-finned cars, and boxy furniture are any indication; an early boomer, Plympton was a teenager in the Eisenhower-Kennedy era, and you can tell that for him those years will always be the classic America from which all other Americas, gorgeous or ugly, idiotic or snazzy, emanate. He came to New York by way of Portland, in the ’60s, to attend the School of Visual Arts, and spent years cartooning and advertising art. But after he began his filmmaking career, recognition didn’t take long: the seminal short Your Face (1987) was nominated for an Oscar, and then MTV became a veritable Plympton showcase, creating animation anthology programs for him, hiring him for all manner of commercials and station IDs, and turning his style and iconic figures into a low-bore national phenomenon.

The Wise Man

Your Face

One of Those Days

How to Kiss

Push Comes to Shove

I Married a Strange Person!

Hair High

Idiots and Angels

Cheatin’

Mutant Aliens

Revengeance