Fever Dreamer: Suzan Pitt’s Feminist Fantasias

Flowers and vegetables pulse, slither, and take dirigible flight; a horse becomes a pampered, petulant lover; a diminutive porcelain mouse transforms into a muscled superhero to save a beleaguered heroine: these are just some of the arresting images in the films of artist and animator Suzan Pitt, whose lushly sensuous, oneiric, and psychosexually charged work created a vital link between two cinematic worlds. On the one hand, the dark surrealism of Pitt’s early work immediately aligned her with the heady, hallucinatory cult cinema of the seventies, defined by now-classic works such as René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet and David Lynch’s Eraserhead. At the same time, her meticulously handcrafted animation drew from deeper avant-garde traditions as well as her own training as a painter and background in theatrical design. Throughout her long career she remained a true multimedia artist, inventively combining techniques to realize her intricate and immersive visions, using cell animation, collage, stop-motion, and sand painting to impart a feverish energy to every frame. Her films renewed the most primal meaning of animation as a mode of bringing forth wondrous life.

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, Pitt displayed artistic talent from an early age, and she would remain in touch with her formative creative experiences by giving special roles to children and childlike innocents throughout her films. Indeed, Pitt frequently mentioned a creepy dollhouse from her youth as a lasting inspiration. She received her formal education at the historic Cranbrook Academy of Art, whose apprenticeship method she would extend in her own later work as a teacher and mentor, first at Harvard and then at CalArts, where she was a longtime and beloved member of that legendary faculty. Pitt’s films put the spotlight on her students, many of whom are credited in key roles, beginning with her early film Jefferson Circus Songs, made while she was teaching at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and in collaboration with local schoolchildren who helped create their own roles.

A good entry point for Pitt’s cinema is her early short Crocus, which makes clear the distinctly feminist estrangement of sexuality central to her first films. Opening with the image of a naked, hirsute man emerging erect, flower-like, from a crown of leaves, Crocus is a family portrait of sorts, observing a naked woman and man engaging in foreplay until they are interrupted by a child in a crib in an adjacent room calling out for water. Rendered as limited mobility paper-doll figures, the amorous couple evokes the tender awkwardness and strangeness of physical intimacy, while the man’s comically oversized erection insists on the woman’s attention with the same total self-interest as the young boy. A telling scene makes clear the film’s playfully introspective and self-reflexive feminist stance by showing the woman as a double image, appearing within the bedroom mirror, giving a wink to the viewer and holding a Bolex camera that she uses to film her other self in bed with the man.

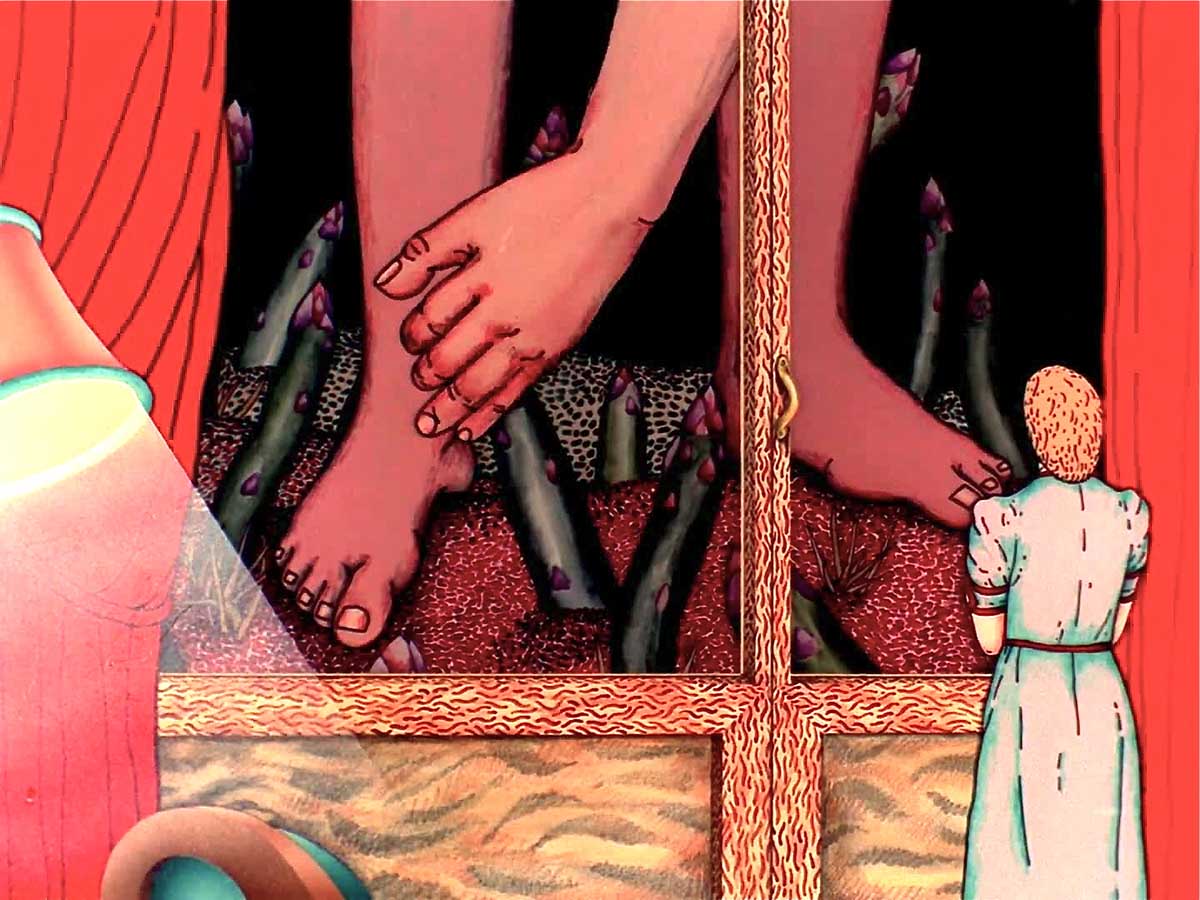

Subtler and more mysterious, Asparagus gives a fuller cinematic dimension to the feminist address of Crocus. The film calls to mind Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon through a ritualized unfolding of time and repeated gestures, including a looping scene in which a woman reaches into a series of inter-nested miniature living rooms. An oblique allegory of alienation and identity, Asparagus follows this faceless woman’s solemn passage through a candy-colored dreamscape of opulent boudoirs, seedy city streets, and a theater staging a hypnotic spectacle of mechanical clouds. The title is reinforced by the prominently sexualized vegetables that drift throughout the film, recurring in different sizes and situations as emblems of primitive fecundity and phallic potency. Like Deren’s experimental film noir, Asparagus uses the slenderest of narratives to structure an intensely self-contained world that turns in upon itself, architecturally and emotionally, opening boxes within boxes, rooms within rooms.

Equally striking is the close dialogue between Asparagus and the work of Lynch, whose debut feature, Eraserhead, was in fact paired with Pitt’s film during its legendary, almost two-year run of midnight screenings in New York and Los Angeles. Asparagus shares with Lynch’s film a postmodern uncertainty of historic time, a sense of pastness folded into a floating present and similarly expressed through evocative settings that meld elements from different periods: thirties Deco meets fifties Googie meets Memphis-style retro-futurism. The unspoken tension that builds across both Lynch and Pitt’s films is deepened and made viscerally palpable by their soundtracks, by the low-voltage industrial current heard throughout Eraserhead, and Asparagus’s taut and haunting electro-jazz score by Richard Teitelbaum.

Asparagus