RELATED ARTICLE

Europa Europa: Border States

By Amy Taubin

The Criterion Collection

En route to the Czech Republic’s Karlovy Vary Film Festival in the summer of 2006, I stopped off for some sightseeing in Prague. Having dutifully made the rounds of the city’s hopping tourist spots, I retreated to my bare-bones hotel in an altogether different part of town. No Kafka-themed tchotchkes here: The working-class neighborhood was dotted with soaring concrete apartment blocks, barely stocked stores and cafeterias, and dour-looking citizens who, refreshingly, felt no obligation to smile for passing tourists.

That

downbeat section of Prague, a relic of Soviet rule from 1968 to 1989, could

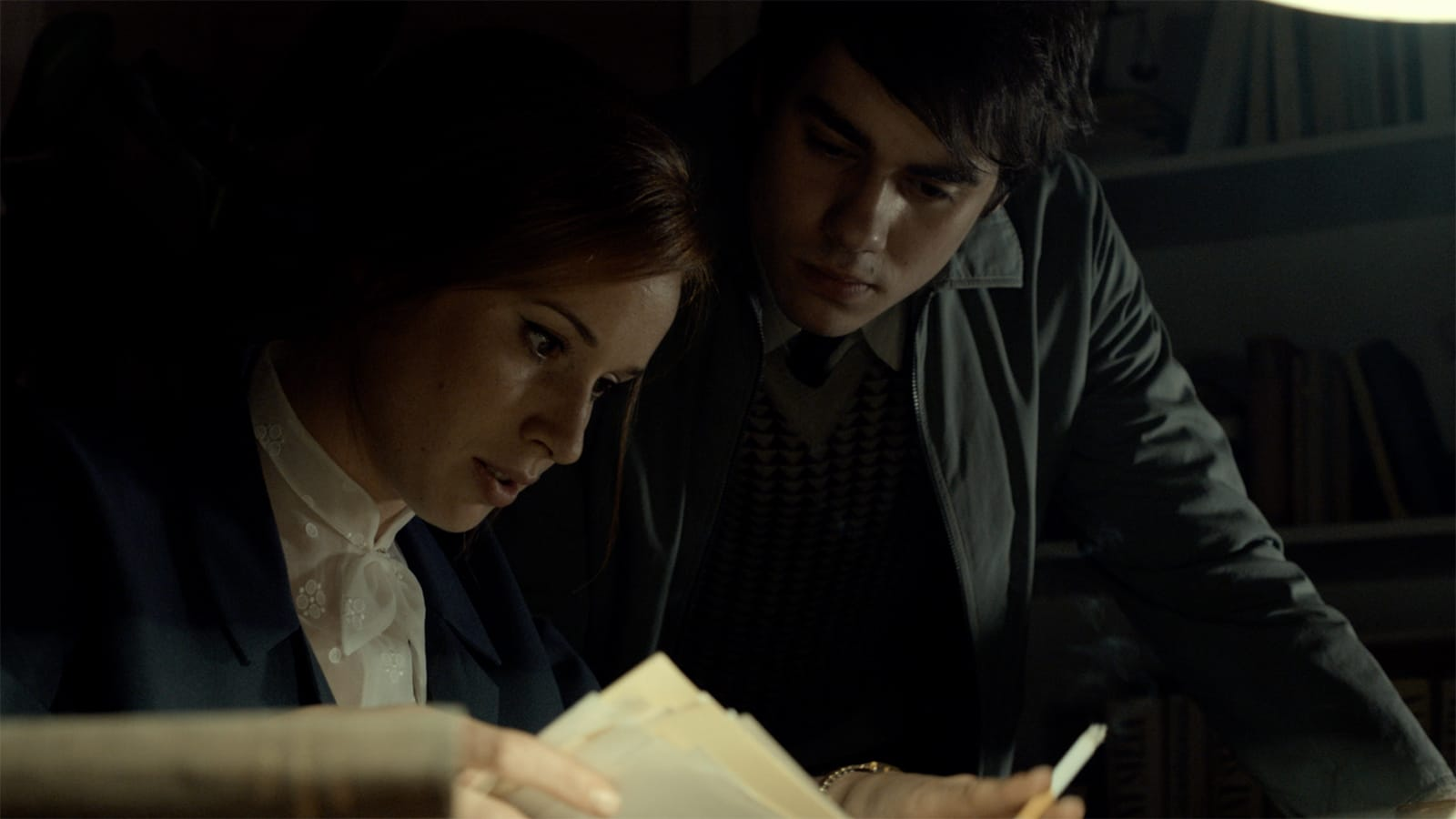

plausibly serve as an era-defining backdrop in Burning Bush, Agnieszka Holland’s magnificent 2014 period drama

about the political fallout from the 1969 suicide of Jan Palach, a student

protesting the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia the previous year.

Made

as a three-part miniseries for HBO Europe and then edited into a film, it was

the Czech Republic’s entry for best foreign-language film at the 2014 Academy Awards,

but was disqualified because it had already been telecast. The presentation on the Criterion Channel

retains the four-hour miniseries in its original form, a political thriller

doubled with an intimately observed chronicle of survival and rebellion in a

country that had briefly tasted democracy before a Warsaw Pact coalition moved

in to brutally dismantle the liberal reforms of the Prague Spring. The plot

centers on the efforts of the Soviet authorities and their Czech flunkies to

spin Palach’s death as a right-wing conspiracy, and to contain the possibility

of copycat suicides triggering an all-out revolt.

I

was a sociology major in my second year at Britain’s London School of Economics

when news broke that the twenty-year-old history student had set fire to

himself in Prague’s Wenceslas Square. Palach left a note calling himself “Torch

No. 1,” calling for a general strike and an end to media censorship, and

threatening that more suicides would follow if his demands weren’t met.

The

LSE—then a cosmopolitan university, founded by Fabian socialists Sidney and

Beatrice Webb, where you could be flanked in class by a fully robed African

prince on one side and the daughter of a local trade unionist on the other—served as a busy hub of England’s 1968 campus revolt, in which I, a

garden-variety London suburbanite fresh from a prim high school for girls, was

no more than a chronically shy peripheral player. Palach’s self-sacrifice made

a deep impression on the part of me that couldn’t shake the queasy feeling that

our elite enclave of the Western

counterculture was playing for comparatively low personal stakes. True, Britain’s campus New Left had honorable

roots in the nuclear disarmament movement and the fight against social

inequality. We marched against apartheid in South Africa, supported the Troops

Out of Ireland movement, railed against corporate fat cats, joined in solidarity

with the American antiwar and other European movements, among them the Prague

dissidents.

We,

too, were fighting the revolutionary fight, but mostly by proxy and at little

cost to us, a privileged subset of a post–World War II generation that had

grown up in peace time without a draft. Our education and health care came

free, courtesy of a generous welfare state funded by successive Labour

governments. None of us was going to Vietnam, and in a relatively open Western

democracy the most punitive repercussions we could expect for our activism were

a rap over the knuckles in court and a night in jail. We didn’t have to watch

what we said, stand on line for food in a stagnant state-controlled economy, or

worry that the student we sat next to might shop us to the secret police.

Some

of the domestic fights we picked were self-indulgent at best, at worst arrogant,

in some cases downright daft. “Free, free the LSE / Take it from the

bourgeoisie,” we chanted, and never mind that as the minority of Brits who

actually made it to university, we were

the bourgeoisie. Disrupting classes on the doubtful principle that our

knowledge was as good as that of our professors—more than a few of whom were

refugees from totalitarian Europe with much to teach us about unfreedom—we

also took the fight home to our parents, defending the Soviet Union in the name

of a socialism increasingly tainted by the emergent horrors of Stalin’s reign.

I was far from alone, on visits to the parental home, in provoking strident

altercations with my father, a former socialist who had helped found an Israeli

kibbutz. “Why don’t you go and live in Russia if you love it so much?” he would

mutter, and rustle his newspaper furiously to indicate case closed.

“Holland’s film handily dispatches my fantasies about the excitement of living on the dissident edge.”