Competition Highs and Lows

When Bong Joon-ho accepted the Palme d’Or for Parasite on Saturday night, he took every opportunity available to express his gratitude to his lead actor, Song Kang-ho. An AFP photo of Bong kneeling and offering up the gold-leafed award to Song has been gathering countless likes and shares all across social media. In Parasite, the first Korean film to win the top award at the Cannes Film Festival, Song plays the head of a destitute family that, one by one, infiltrates a vastly wealthier family. Most agree with Giovanni Marchini Camia, who writes at the Film Stage that “Bong has crafted an angry, genre-inflected social allegory that in many ways functions as a Korean analog to Jordan Peele’s Us. A far superior craftsman than Peele, Bong is perhaps the contemporary master of entertaining, intelligent, and resolutely political cinema. In our age of assembly line blockbusters, he’s a veritable treasure.”

Parasite is the fourth collaboration between Bong and the actor who’s also worked repeatedly with Park Chan-wook and Kim Jee-woon and appeared in films by Hong Sang-soo and Lee Chang-dong. In August, the Locarno Film Festival will present its Excellence Award to Song, and many in Cannes thought he might be a strong contender for this year’s best actor award. Instead, it’s gone to Antonio Banderas for his turn as a filmmaker not at all unlike Pedro Almodóvar in Pain and Glory. Time’s Stephanie Zacharek suggests that “Banderas’s performance—although he’s nearly always terrific, this is quite possibly his finest—is so fine-grained in its attentiveness to every nuance of physical and psychic suffering that you can’t help thinking Almodóvar is speaking through him.” More than a few critics were hoping that Almodóvar’s sixth run for the Palme would, for the first time, go all the way, Banderas included. Accepting the award, he said that the film’s title reflected his own conflicting feelings. Pained that the man who’d previously directed him in films such as Matador (1986), Law of Desire (1987), and Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989) couldn’t join him on stage, Banderas nevertheless basked in his moment of glory.

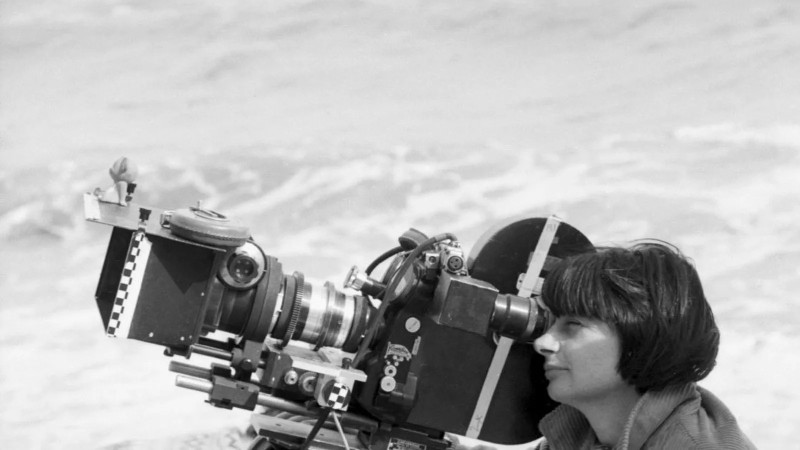

Yet another fruitful collaboration was celebrated when the best screenplay award went to Céline Sciamma, who’s directed Adèle Haenel, her real-life partner and the star of her 2007 debut Water Lilies, in Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Scan the grids tabulating critics’ ratings of the films in competition this year, and you’ll find that Portrait, also the winner of the Queer Palm, consistently ranks among the top three alongside Parasite and Pain and Glory. In Portrait, set in the eighteenth century on an island off the coast of France, Haenel plays Héloïse, who’s resisting her titled parents’ plans to marry her off to a wealthy man in Milan. They give Marianne (Noémie Merlant) one week to pose as their daughter’s walking companion by day, and to spend her nights committing Héloïse’s image to a canvas that would be sent to Italy for the future husband’s approval. No one involved foresees Héloïse and Marianne falling in love.

As the A.V. Club’s A. A. Dowd observes, Portrait is the story of “a mutual, slow-motion seduction, and it seduces its audience just as gradually and effectively, pulling us into its old world with the beauty of its images and the quiet efficiency of its storytelling.” The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw is reminded of Alfred Hitchcock, “actually two specific Hitchcocks: Rebecca, with a young woman arriving at a mysterious house, haunted by the past, and also Hitchcock’s Vertigo, with its all-important male gaze. Sciamma flips it to a female gaze, a gaze of connoisseurship, of artistic appropriation, of erotic rapture.” Sciamma also “brings the erotic together with the cerebral,” adds Bradshaw, and in Another Gaze, Rebecca Liu notes that Héloïse and Marianne “argue about what’s more important: adhering to the formal rules of portraiture, or pursuing more malleable notions of capturing spirit and playing with feeling. Portrait de la jeune fille en feu—a study of two women pursuing lives larger than the ones they’ve been given—chooses the spirit over formalism; poetry over realism; myth over history.” Neon will be bringing both Portrait and Parasite to the States later this year.

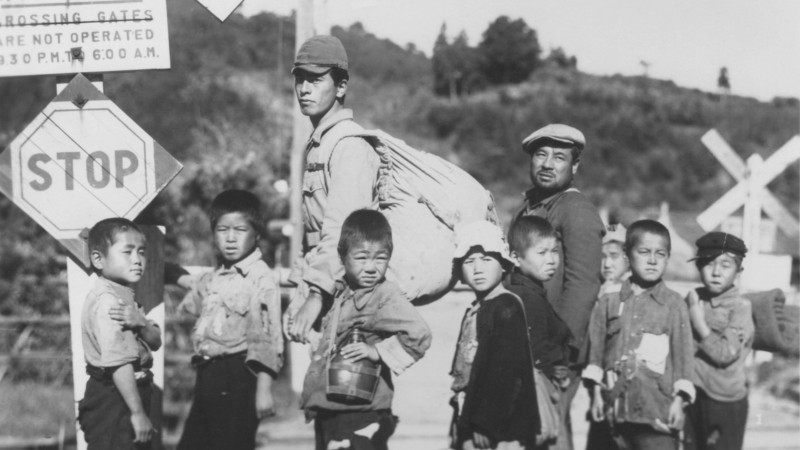

Haenel had quite a festival, appearing not only in Portrait but also in Quentin Dupieux’s Deerskin, which opened the Directors’ Fortnight, and in Aude Léa Rapin’s Critics’ Week entry Heroes Don’t Die; Film Comment editor Nicolas Rapold talks with her about all three films. Though she’s been working in film and television since 2002, she didn’t really break through internationally until she took the lead in Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne’s The Unknown Girl in 2016. This year, the Dardennes brought Young Ahmed, the story of a thirteen-year-old Muslim (Idir Ben Addi) so radicalized by an extremist imam (Othmane Moumen) that he plans to murder his teacher (Myriem Akheddiou). In the New York Times, Manohla Dargis notes that, when it was announced that the award for best director was going to the Dardennes, the assembled press “erupted in vigorous boos.” The Dardennes “have won the Palme d’Or twice and their influence on contemporary cinema is profound, as was evident throughout the festival,” writes Dargis. “But their new movie was seen by many critics as a disappointment.”

For Richard Porton at the Daily Beast, what’s “truly depressing about Young Ahmed is the filmmakers’ capitulation to a schematic analysis of Islamism that is completely unedifying. Other Dardenne brothers films such as La promesse or L’enfant deal with characters grappling with complex moral choices. Ahmed, by contrast, is a static abstraction.” At Little White Lies, Charles Bramesco adds that the ending “in particular suffers from this absence of innate understanding, giving the filmmakers an easy way out from the questions of penance and forgiveness that’s nagged so many of their past characters.”

No one’s objected to the decision by the jury—Alejandro González Iñárritu (president), Enki Bilal, Robin Campillo, Maimouna N’Diaye, Elle Fanning, Yorgos Lanthimos, Pawel Pawlikowski, Kelly Reichardt, and Alice Rohrwacher—to award the Grand prix to Mati Diop’s Atlantics. Essentially, this means that the feature debut by the first film in competition to have been directed by a black woman has placed second. Introducing his interview with Diop for Film Comment, Eric Hynes calls this love story set in contemporary Dakar “a mix of classical storytelling and genre gambits—a practical love contrasted with one of passion, a detective story, a haunting—with unique stylizations, from subjective music cues to provocative reverses and long takes.”

This year’s jury prize is shared by Ladj Ly’s Les misérables, an electric depiction of tensions between immigrants and the police in a Parisian banlieue, and Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles’s Bacurau, a violent and unpredictable story of the invasion of a small town in rural Brazil. The best actress award goes to Emily Beecham for her performance as a genetic engineer who’s created a plant that makes people happy in Jessica Hausner’s Little Joe.