Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood

On Monday, the day before Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood premiered in competition in Cannes, Quentin Tarantino sent out a brief open letter requesting that attendees keep any and all spoilers to themselves. So far, and to varying degrees, reviewers have complied. But not all of them are happy about it. Dispatching to Sight & Sound, Jessica Kiang finds it frustrating that “we can’t talk about the only thing (extremely) wrong with a film that is otherwise an absolute blast, a pure, giddy rush of thrillingly confident, expansive filmmaking that showcases the most resonant and satisfying storytelling Tarantino has given us in over two decades.” Not everyone agrees that what the Telegraph’s Robbie Collin calls the “Tarantinification” of the Manson Family murders is, in fact, “(extremely) wrong,” but we’ll get to that.

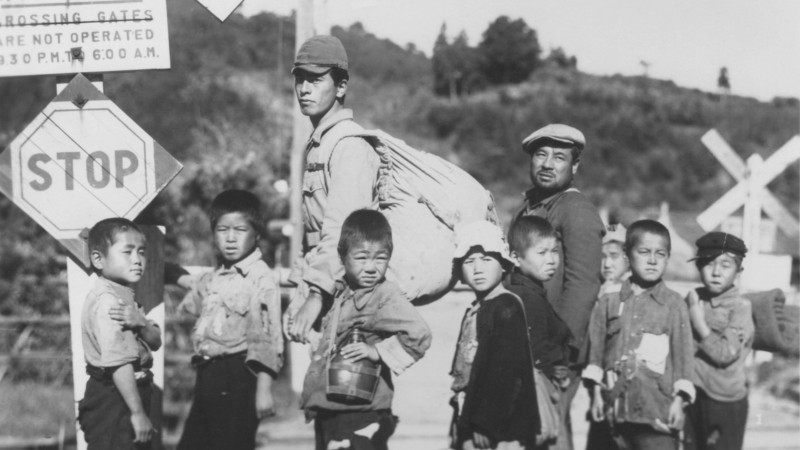

Like many a good Hollywood story, Once Upon a Time is divided into three acts, but here, each of them plays out over the course of a single day in Los Angeles: February 8, 1969; the following day; and then, leaping ahead half a year, August 8, the day that ended with the hideous slaying of actress Sharon Tate, who was eight and a half months pregnant, and four other people. Talking to Esquire’s Michael Hainey, Tarantino says that Once Upon a Time is “probably my most personal” film. As a “memory piece,” it’s not unlike what Roma is to Alfonso Cuarón, he says. “This is me. This is the year that formed me. I was six years old then. This is my world. And this is my love letter to L.A.”

Sitting in on the interview—and it’s a relaxed, reflective, and rewarding read—are two of the film’s top stars, Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt. DiCaprio plays Rick Dalton, the star of Bounty Law, a hit television series whose run ended in 1963, and Pitt is his able stuntman, cheerful gofer, and only friend. “DiCaprio’s Rick looks mischievously boyish,” writes Time’s Stephanie Zacharek, “though you can’t help noticing the tiny crow’s feet marking the skin around his eyes, etched there by dried-up work and dwindling bank accounts—there’s an alluring, Robert Ryan-style weariness about him. And Pitt is superb, striding through the movie with the offhanded confidence of a mountain lion who knows his turf. This is swagger freed from self-consciousness; Cliff was groovy before the word was invented.”

Dalton’s agent (Al Pacino) encourages him to go to Italy and make a few spaghetti westerns—the designers at BLT Communications, LLC, by the way, have dreamed up a fewoutstandingposters for them. But Dalton sees a more promising opportunity in his new neighbors on Cielo Drive, Roman Polanski and his new wife, Sharon Tate. She’s played by Margot Robbie, who, according to Leonardo Goi in the Notebook, “truly does grace each scene she’s in with effortless bravado, her Tate smiling at her image on the silver screen with a contagious, engrossing blend of innocence and stupor.”

Dalton can sense a new Hollywood rolling in, and Polanski just might be his ticket to ride. “When Rick enthuses about Polanski, it is hard not to hear Tarantino’s voice in the character’s excitement,” writes Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “In some ways, Polanski reads like a tragic variation on Tarantino, a kind of horrific doppelgänger, which is one reason, I think, that this movie feels more personal than some of his recent endeavors. He loves this world so much, and that adoration suffuses every exchange, cinematic allusion, and narrative turn.”

As Bilge Ebiri reminds us at Vulture, Tarantino “burst onto the scene in the 1990s like a DJ-prophet of the cultural trash heap, reclaiming lost films and shows and songs, but also attitudes and speech patterns and even fashion choices, presenting them back to us in a way that made them irresistible, prompting an entire generation to start emulating his obsessions. But for all that, his universe has always been a dark, twisted, cruel one. Here, more than in any other film Tarantino has made, we sense that we’re watching a world that he might want to live in.” At the Playlist, Guy Lodge finds these first two hours of Once Upon a Time to be “a kind of gorgeously lacquered mega-budget hangout movie, cruising happily and chattily between the director’s pet obsessions of B-movies, junk TV, and crummy, charismatic men shooting the shit at a particular rhythm that only one man in Hollywood can write.”

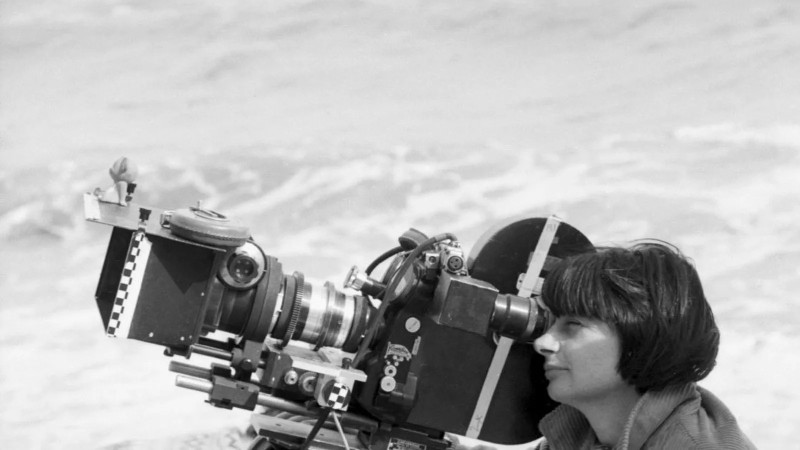

For Jessica Kiang, Robert Richardson’s “gorgeously fine-grained, glowy 35 mm writes the filmic equivalent of a Joan Didion essay on the prelapsarian, doomed LA of the late 1960s.” Which is why Ben Kenigsberg at RogerEbert.com recommends seeing Once Upon a Time projected from a 35 mm print. This is “an ambience-driven movie: Tarantino fetishizes old posters, records, cars, and home decor. Characters go to drive-ins and movie theaters and gather around TVs (during an era when shows were shot on celluloid) for communal viewing. Watching this story on a digital medium would feel false; it needs to look lived-in, worn, graspable.”

Tarantino tells Michael Hainey that his ninth feature is “in the same vein as, like, The Stunt Man or Singin’ in the Rain or any other movie about Hollywood. And there’s a good-hearted spirit to it. Then you ask, ‘How does the Manson Family fit in?’ Well, that’s the trick . . . It’s like we’ve got a perfectly good body, and then we take a syringe and inject it with a deadly virus.” Which brings us to what Robbie Collins suggests “must be the single most shocking sequence in Tarantino’s filmography . . . There’s a gleeful toxicity to it that will launch a thousand think-pieces.”

For the Los Angeles Times’ Justin Chang, the final act of Once Upon a Time is “funny, scary, troubling, and exhilarating by turns; the meandering structure clicks into place as it becomes clear where Tarantino has been taking this story . . . This is hardly the first time that this director has turned fiction and reality into blood-slicked bedfellows; nor is it the first time he has made the outrageous suggestion that cinema, as both an art and an industry, can make up for some of life’s most grievous imperfections in ways that nothing else can. Spoilers or no spoilers, you may not be terribly surprised, which doesn’t mean you won’t be astonished.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.