Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life

Is A Hidden Life a “return to form” for Terrence Malick, as Charles Bramesco announces at the Playlist? Is Malick “back,” as David Ehrlich declares at the top of his review at IndieWire? Since Sunday night’s premiere in Cannes’s competition of the fifth feature Malick has made after winning the Palme d’Or in 2011 for The Tree of Life, critics have been sharply divided not only over the answer to such questions but also over the inherent supposition. Many would argue that Malick’s recent work, released in what seems like a mad rush compared to the sparse output of four pre-Tree features over the course of three decades, more than measures up to the bar set by his landmark 1973 debut, Badlands.

Others see Malick falling into a formulaic rut, having honed a style—revelatory to some, grating to others—that Peter Bradshaw sums up well when he writes in the Guardian that it offers “an overpowering sense of being ecstatically, epiphanically in the present moment, an ambient feeling of exaltation created by a montage of camera shots swooning, swooping, and looming around the characters who appear often to be lost in thought, to an orchestral or organ accompaniment, and a murmured voiceover narration of the characters’ intimate but distinctly abstract feelings and memories.” Notebook editor Daniel Kasman argues that this is “a coherent and, for me, frequently tremendous and moving approach not to storytelling but to the evocation of the spirit.”

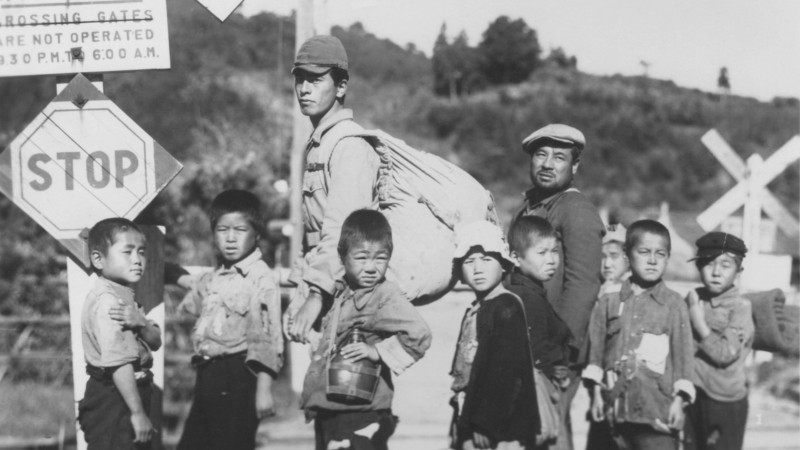

A Hidden Life is based on the true story of Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl), a farmer who lived with his wife (Valerie Pachner) and three daughters in St. Radegund, a tiny, Edenic town tucked into the Austrian Alps. Two years after Hitler’s annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938, Jägerstätter was called up to serve, completed his military training, and returned to the farm. In 1943, he was called up again, but as a Christian who abhorred all that the Nazis stood for, he refused to swear an oath of loyalty to the Führer, fully aware that the penalty would be death. At the Daily Beast, Richard Porton suggests that this story is “almost tailor-made to fit Malick’s cinematic agenda,” given that the director “has a well-known penchant for protagonists who spurn the material world for higher spiritual callings.”

At the same time, it might be pointed out, as Barbara Scharres does at RogerEbert.com, that a “little research into the historical Jägerstätter,” who was declared a martyr and beatified by the Catholic Church in 2007, “reveals that he was a far more complex, widely experienced, traveled, and educated character than Malick’s holy peasant, as was his wife, but this is, after all, Malick’s film, and his fictionalized vision.” To return to Peter Bradshaw for a moment, it seems to him that the “nature of Franz’s intensity” is “not all that different from the intensity of Ryan Gosling’s thoughtful singer-songwriter in Malick’s Song to Song (2017), or Christian Bale’s tortured screenwriter in Knight of Cups (2015), or Ben Affleck’s engineer in To the Wonder (2014), whose woes are considerably less pressing . . . It is as if Malick has taken Jägerstätter and enclosed him in exactly that same hermetically sealed environment of heightened awareness of the present moment, and unawareness of the larger context.”

The A.V. Club’s A. A. Dowd finds it “frankly a little troubling” to see “such a violent, devastating era reduced to another whispery ballet of nature.” By contrast, The Thin Red Line (1998), “the director’s previous and vastly superior film about the war, offset the idyllic tranquility with chaos and horror.” Time’s Stephanie Zacharek argues that A Hidden Life is “a sermon brimming with oversimplified thought” that “tells us nothing new about evil or our need to take a stand against it; it barely makes us feel what it’s like to stand against evil. All it has to offer is soft-focus piousness. Its ethical purity is inert, a dead butterfly in a jar.” More than a few critics have questioned Malick’s decision to have the characters, all of them German or Austrian, speak English until the shouting starts. That’s when the dialogue switches to German. “Obviously,” writes Sight & Sound editor Nick James, “to Malick, good and evil speak different languages.”

The late Bruno Ganz speaks English when, as the presiding judge at Jägerstätter’s trial, he pleads with the conscientious objector to save his own life, to recognize that his resistance will ultimately have zero effect. The clergy, too, argues that God judges not what a man does but what’s in his heart. At the Film Stage, Leonardo Goi writes that A Hidden Life “achieves the miraculous feat of both jibing at religious institutions, while celebrating faith as something that transcends them, something mysterious to cherish and behold.” David Ehrlich, too, argues that the film is “a lucid and profoundly defiant portrait of faith in crisis.”