Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory

Since its first screening in Cannes on Friday night, Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory has been riding high on the grids tabulating ratings from critics from around the world posted at the International Cinephile Society,Ioncinema, Screen International, and Todas Las Críticas. It isn’t faring quite as well, though, with the critics’ jury assembled by the German site critic.de. This is Almodóvar’s sixth film to be invited to the competition, and while he hasn’t yet won a Palme d’Or, he has scored a best director win for All About My Mother (1999) and another for best screenplay for Volver (2006). When Pain and Glory opened in Spain in March, it was met with strong reviews, and Manuel Yáñez-Murillo wrote an outstanding, context-rich appreciation for Film Comment, in which he called the film “a fearless act of self-exposure in personal, artistic, and historical terms—a double-edged brushstroke of melancholy and lust for life, and a sublime addition to the Almodóvar pantheon.”

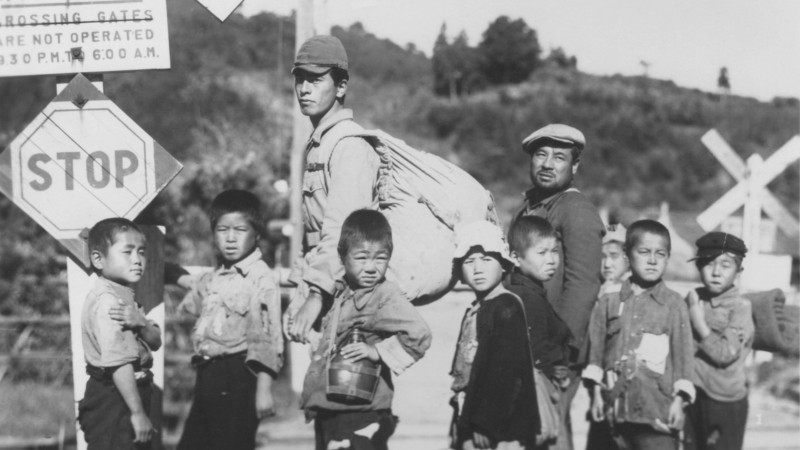

As aging and ailing filmmaker Salvador Mallo, Antonio Banderas is clearly and unapologetically playing a stand-in for Almodóvar, not unlike, as a good handful of reviewers have pointed out, Marcello Mastroianni did for Federico Fellini in 8½ (1963). Salvador has been creatively blocked for a while when he’s asked to present a restoration of one of his major works, a film called Taste that would have been released at around the same time as Almodóvar’s Law of Desire (1987), which starred a young Banderas. The event leads to Salvador’s reunion with an estranged friend, the actor and star of Taste, Alberto Crespo (Asier Etxeandia), who introduces Salvador to heroin. The drug not only ushers in a wave of flashbacks to Salvador’s youth and memories of his mother (Penélope Cruz) but also does wonders for his many ailments, including chronic back pain and panic attacks. “Since Almodóvar has gone to such lengths as to exactly reproduce his own apartment, right down to the book spines,” writes Sight & Sound editor Nick James, “we can take this portrait as a selfie and wonder, in that case, how he managed to make such an elegant, wistful, and mischievous film if he is so afflicted.”

Variety’s Peter Debruge agrees that Pain and Glory is “a mature work of meticulously tuned metafiction, erupting with so many of the director’s signature touches—bold colors, passionate embraces, and copious references to his cinematic inspirations (from Liz Taylor to Fellini), all wrapped up in what is Alberto Iglesias’s best score—while making a conscious decision to reject broad melodrama in pursuit of a subtler, more direct form of authenticity.” The Los Angeles Times’ Justin Chang welcomes Almodóvar’s evolution as well, noting that, as in Julieta (2016), “the moving and underappreciated picture he made before this one, Almodóvar has learned to work with a new economy: The colors are more somber and muted than usual (which doesn’t make the images any less eye-popping), and the usual incursions into farce and melodrama have been pared away. But if the tone is more restrained, more elegiac, and lacking that signature Almodóvar outrageousness, the emotional force still knocks you sideways.”

For Adam Woodward at Little White Lies, too, Pain and Glory is “an absolute world-beater.” The film has reunited Almodóvar with several of his past key players, but it’s Banderas, he argues, “who makes the most telling contribution. At fifty-eight, he remains a charismatic and commanding presence, and although his eyes still have that unmistakable movie star sparkle, there’s a certain vulnerability and a world-weariness behind them now.” The Telegraph’s Tim Robey also appreciates Banderas’s “impressively honest and touching performance,” but he’s got a problem with Salvador as a character in that “his outlook on life, art, everything, seems so much dimmer, and weirdly vainer, than Almodóvar’s own.”

Among the dissenters is the A.V. Club’s A. A. Dowd. “What’s missing from the movie,” he writes, “is any real sense of danger or subversion—qualities that used to basically define this once-radical filmmaker’s work.” For the Hollywood Reporter’s Jonathan Holland, the film “may be exquisitely crafted, but it’s also dangerously comfortable, so that strangely enough, what’s touted as being the director’s most personal effort to date comes across as an oddly detached and impersonal exercise in brilliant style.” It’s Barbara Scharres at RogerEbert.com who comes down hardest on Pain and Glory, calling it “a thudding, graceless film that lacks the fleet sense of wit and the narrative cohesion that marks Almodóvar’s best work.”

Pain and Glory will arrive in the States in October, and for now, most critics would agree with Film Stage contributor Ed Frankl, who’s right on board with the film all the way through a final “twist that encapsulates an entire career of self-expression in a magnificent flourish. This is perhaps the director’s most outstanding work since his peerless fin-de-siècle diptych of Talk to Her and All About My Mother.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.