Memories of Taboo-Buster Dušan Makavejev

No filmmaker of his generation from Eastern Europe could match the charisma and originality of Dušan Makavejev. Forever bustling from festival to festival with his inspiring wife Bojana Marijan—who contributed to the sound and music on many of his works—he embodied all that was best in Tito’s Yugoslavia. Long before the six republics descended into bitter, vicious wars of attrition with one another, Makavejev was a unifying spirit, the cynosure for all filmmakers in Yugoslavia. Serbian born and bred, he inspired contemporary directors from Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Macedonia, and Montenegro with his passionate discourse and his broad-minded dialectic. Over the years his voice grew huskier and his hunched back more pronounced, but his curiosity remained undiminished. He disarmed his critics with a laugh or a quip. “We in Yugoslavia are 100% Marxist,” he loved to repeat, “50% Groucho and 50% Karl.”

Makavejev was “First Secretary” of the Belgrade Film Archive Club in 1954 when Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Française arrived in Belgrade with a diplomatic trunk filled with works by Clair, Feuillade, and Pagnol and other classics of French cinema—all uncensored. In the years that followed, “Wajda’s trilogy made a huge impression on me,” he told me in 2001. “Then came Jules and Jim, Breathless—freedom of editing without careless editing, plus the casual treatment of the story, with casual dialogue. I liked the dancing camera in Chabrol’s À double tour. He was for me probably more important than anyone else in the early days. Some of the images from Les bonnes femmes have stayed with me for forty years.”

Like many aspiring directors in Eastern Europe, Makavejev had to cut his teeth on shorts and documentaries, which set the template for his love of reportage and realism in future years. “One of my amateur films was screened at a festival of amateur cinema in Cannes in 1957. A group of us film society members traveled with two tents to the Riviera in December, and found a place to set them up in the hills behind the railroad at the back of the town, where the Algerians lived, and for one franc a day you could erect your tent!” His maiden feature, Man Is Not a Bird, released in 1965 and selected the following spring for the Critics’ Week in Cannes, revealed a socially committed filmmaker who took risks with both form and content, flashing forward and backward in time as it tells the tale of an engineer visiting the copper-processing town of Bor and falling for a young hairdresser. The visuals are bleak, but Man Is Not a Bird has an irreducible humor and impudence that deftly sidesteps pessimism.

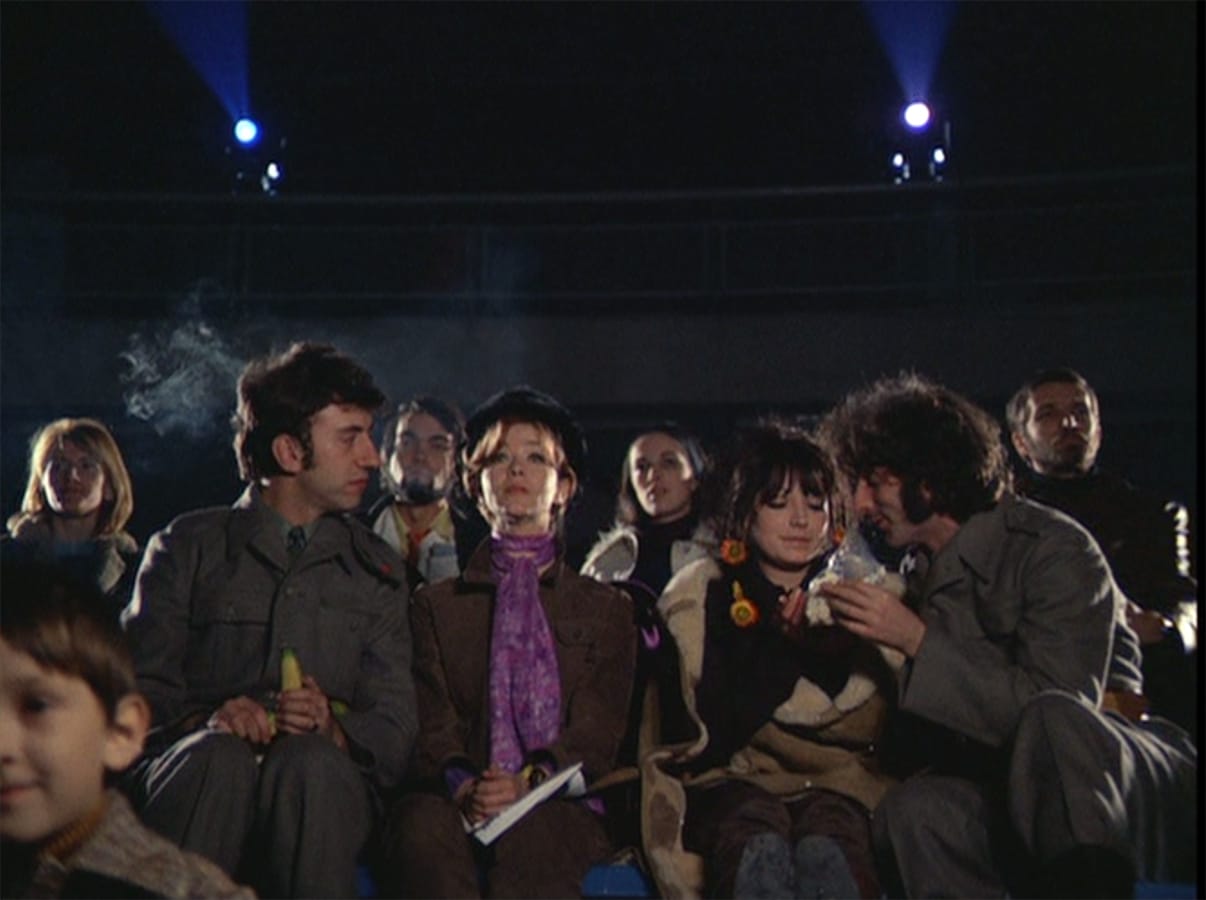

Sweet Movie

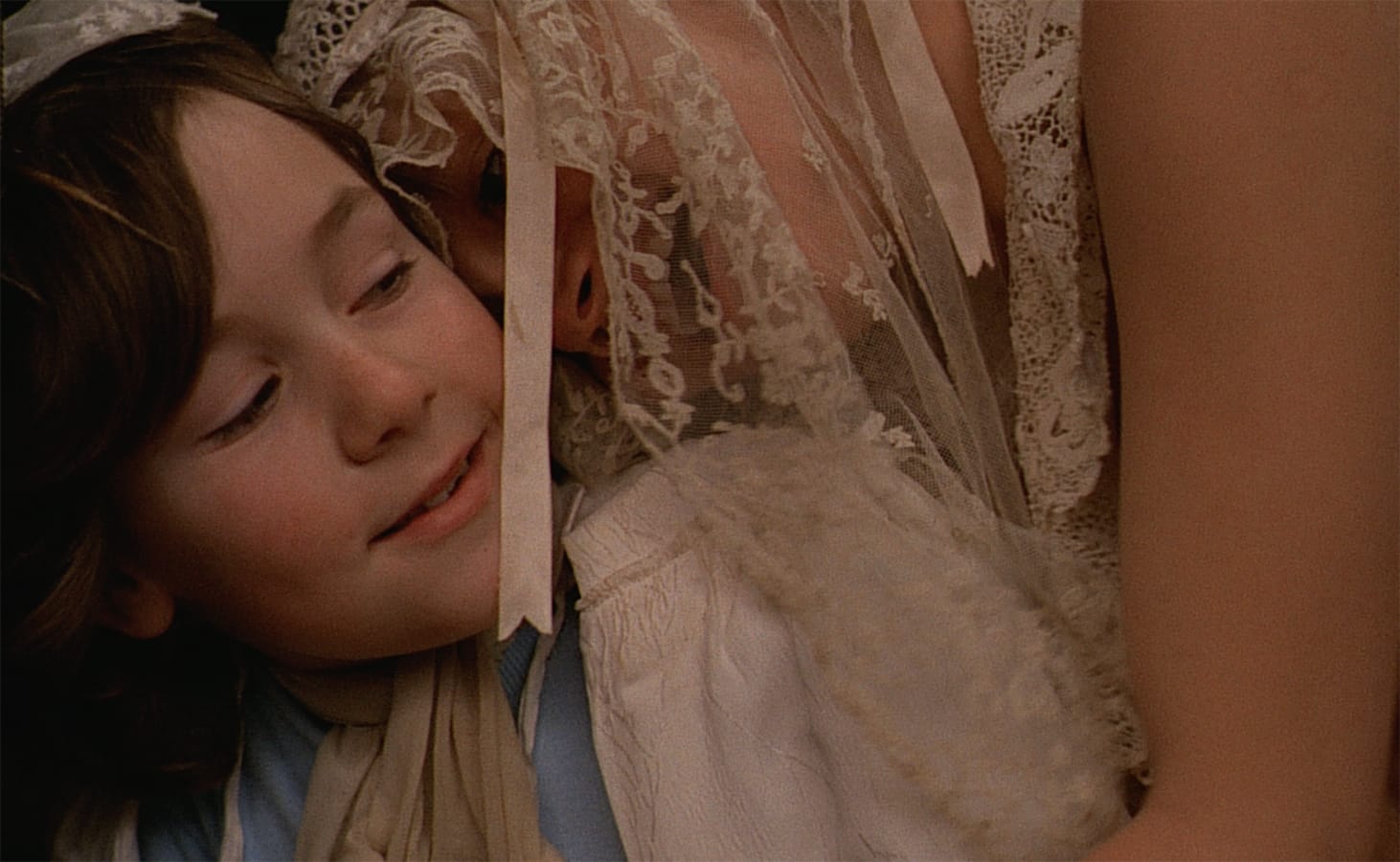

WR: Mysteries of the Organism