Nights of Cabiria

The subject of loneliness and the observation of the isolated person has always interested me. Even as a child, I couldn’t help but notice those who didn’t fit in for one reason or another—myself included. In life, and for my films, I have always been interested in the out-of-step. Curiously, it’s usually those who are either too smart or those who are too stupid who are left out. The difference is, the smart ones often isolate themselves, while the less intelligent ones are usually isolated by the others. In Nights of Cabiria, I explore the pride of one of those who has been excluded.

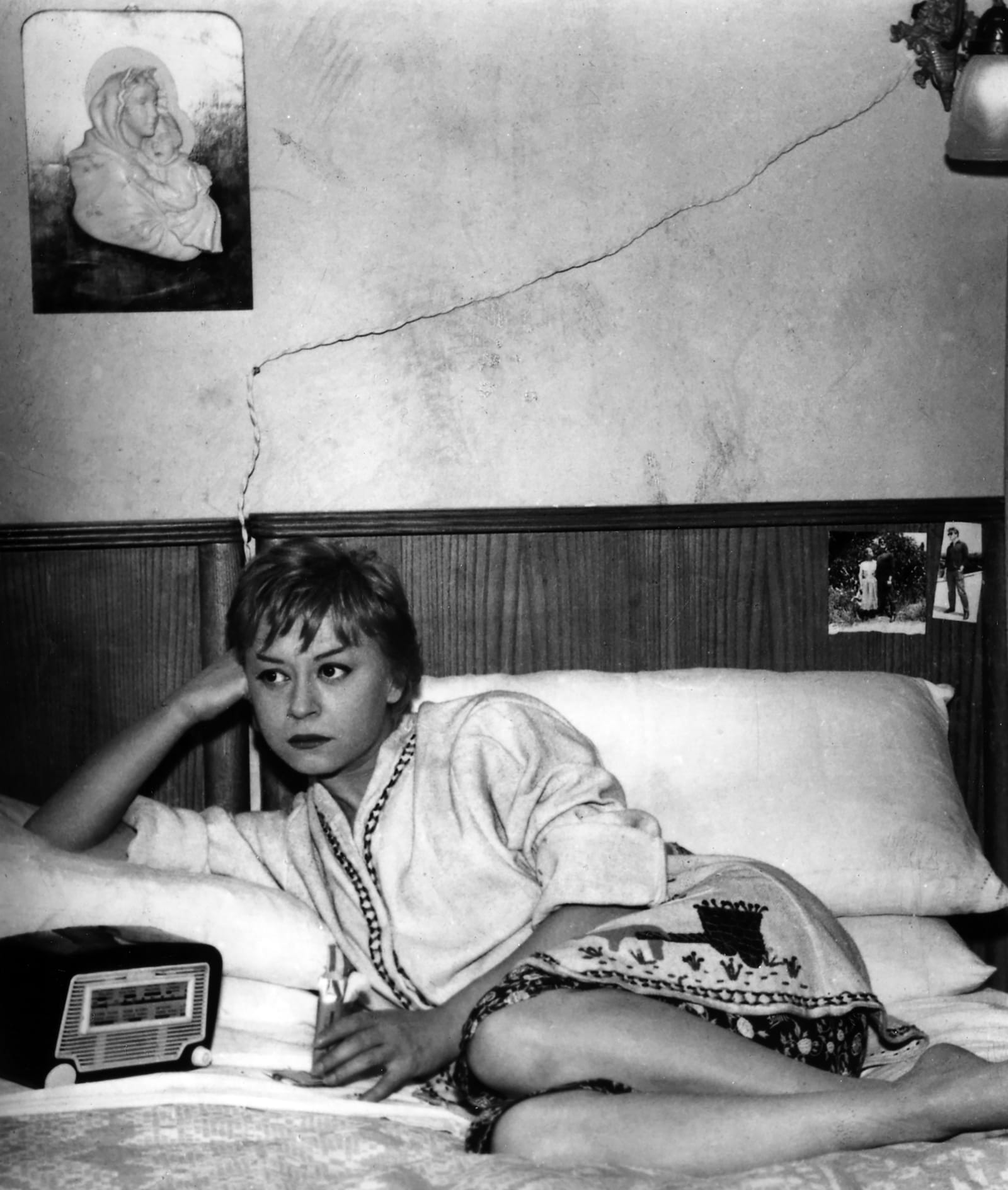

The brief appearance of the Cabiria character near the end of The White Sheik revealed Giulietta’s acting abilities. As well as being an excellent dramatic actress in Without Pity and Variety Lights, she revealed herself capable of being a tragicomic mime in the tradition of Chaplin, Keaton, and Toto. In La Strada, she emphatically reinforced this impression. Gelsomina grew out of her original brief Cabiria portrayal, and at the time I sensed that Cabiria had the potential for an entire picture based on her character, starring, of course, Giulietta.

During the shooting of Il Bidone, I met a real-life Cabiria. She was living in a little hovel near the ruins of the Roman aqueduct. At first, she was indignant at my disruption of her daytime routine. When I offered her a lunch box from our food truck, she came closer, like a small homeless female cat, an orphan, a waif, maltreated and living in the streets, but still very hungry, hungry enough to overcome her fears with the offer of food.

Her name was Wanda, a name I might have made up for her if it hadn’t already been hers. After a few days, she communicated with me, though in her inarticulate way, some of the circumstances of being a streetwalker in Rome.

Goffredo Lombardo had the option for my next picture. He was appalled by the idea of a story about a prostitute, an unsympathetic character as far as he was concerned, and he found his excuse to back out of the deal. He wasn’t unique. Quite a few producers didn’t like the idea, especially after the box-office failure of Il Bidone. There is a story which is often quoted about something I said when I offered the script of Nights of Cabiria to a producer. Sometimes the same story is told, but a different film is substituted.

The producer says, “We have to talk about this. You made pictures about homosexuals”—and I suppose he is referring to the Sordi character in I Vitelloni, though it is not a point I made specifically—“you had a script about an insane asylum”—he is referring to one of many scripts that was never filmed—“and now you have prostitutes. Whatever will your next film be about?” As the anecdote goes, I respond angrily, “My next film will be about producers.”

I can’t imagine how that story got started, unless I started it myself, but I don’t remember doing that. I don’t remember saying it, but I wish I had. More often, I’m the kind of person who thinks of what I wish I’d said after the occasion has passed, and it’s a little embarrassing to call back a day late with one’s quick retort.

There is no connection between my Nights of Cabiria and an early silent Italian film called Cabiria, which was based on a story by Gabriele D’Annunzio. If there was any influence on me, it was Chaplin’s City Lights, one of my favorite films. Giulietta’s portrayal of Cabiria reminds me, as it has many people, of Chaplin’s tramp, even more so than her Gelsomina. Her exaggerated dance in the nightclub is reminiscent of Chaplin, and her encounter with the movie star is similar to that of the tramp’s encounter with the millionaire, who recognizes Charlie only when he’s drunk. I leave Cabiria looking at the camera with a glimmer of new hope at the end, just as Chaplin does with his tramp in City Lights. It is possible for Cabiria to yet again have hope because she is so basically optimistic, and her expectations are so low. The French critics referred to her as the feminine Charlot, their affectionate name for Chaplin. That made her very happy when she heard it. I was happy, too.

For Giulietta’s wardrobe, we went to a street market to shop for the clothes Cabiria would wear. Afterwards, because she wasn’t going to have pretty clothes to wear in the film, I took her to an expensive boutique to buy a new dress for herself.

Incidentally, the “man with a sack” sequence, which only the audience at Cannes saw, still exists and could be restored in future versions, as could a great many of the cuts I was forced to make in my films. After so many years, however, I don’t know how I would feel about it. I think the scene is especially good, but with or without it, the film stands on its own, so I feel lucky that it was the only part about Cabiria with which the Church found unacceptable for Italian audiences. The man with a sack had food in his pack, and he went around feeding the homeless of Rome who were hungry. This was based on a real-life character I actually saw. There were those in the Church who objected, saying that it was the role of the Church to feed the homeless and hungry, and that I had made it seem the Church wasn’t doing a good job with its responsibility. I could have responded that the man with a sack was a Catholic, a very good example of a Catholic who was taking individual responsibility, but I didn’t know to whom I should tell this.

I understand that the term auteur to describe a cinema director was first used in talking about me, by the French critic André Bazin in a review of Cabiria. The American Broadway musical comedy and Hollywood picture Sweet Charity was inspired by Nights of Cabiria, and my name is on the credits, but I disagreed with Bob Fosse’s way of doing it on so many points, I prefer that the film be regarded as his creation.

The positive nature of Cabiria is so noble and wonderful. Cabiria offers herself to the lowest bidder and hears truth in lies. Though she is a prostitute, her basic instinct is to search for happiness as best she can, as one who has not been dealt a good hand. She wants to change, but she has been typecast in life as a loser. Yet she is a loser who always goes on to look again for some happiness.

Cabiria is a victim, and any of us can be a victim at one time or another. Cabiria is, however, more of a victim personality than most. Yet even so, there is also the survivor in her. This film doesn’t have a resolution in the sense that there is a final scene in which the story reaches a conclusion so definitive that you no longer have to worry about Cabiria. I myself have worried about her fate ever since.

Excerpted from I, Fellini (1995) by Charlotte Chandler. Reprinted by permission of the author.