The Art of the Dream Sequence

Artists across all mediums have long been obsessed with the challenge of evoking dream states, but film—with its oneiric combinations of light and shadow, and its ability to manipulate time and space—has particularly uncanny access to our nighttime reveries. Whether lending visual form to unconscious fears and desires or transporting us to visions of the past, a dream sequence opens a portal to a character’s inner life. In celebration of our release of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, the Japanese master’s visually stunning odyssey into his own imagination, we’ve gathered a few of our favorite examples of dreaming on-screen.

Ivan’s Childhood

Andrei Tarkovsky’s debut feature is a harrowing coming-of-age tale, structured around the dreams of a young boy growing up amid the the horrors of World War II. The film is an adaptation of a novella by Soviet writer Vladimir Bogomolo, but as Dina Iordanova notes in her essay for our release, Tarkovsky and his friend Andrei Mikhalkov-Konchalovsky wanted to give the narrative “a poetic dimension, mostly achieved by interplay between reality and dream.” The film’s second dream sequence showcases a style of mise-en-scène that would “become a key element in Tarkovsky’s later, visually dialectical style, which often prefers to show protagonists twice in a scene, from perspectives above and below, both within a situation and observing it from the outside.”

Un carnet de bal

Filled with the kind of lyrical imagery that became a trademark of French director Julien Duvivier’s career, Un carnet de bal tells the story of a wealthy widow mourning a romance from her youth. In the above sequence, the heroine begins to fall asleep, then a dissolve transports us to a ballroom from her past. “We see a row of curtsying women in white,” writes Michael Koresky, “each grabbed by a partner and twirled away in rhapsodic slow motion. Adding to the scene’s eeriness, composer Maurice Jaubert had his musicians play the score backward, then reversed the recording. It’s a fitting first act for a film that depicts the past as a romantic illusion.”

Le grand amour

Pierre Etaix’s playful takedown of bourgeois marriage boasts a wildly inventive set piece in which the hero fantasizes about lying in bed with his young secretary amid a traffic jam of other bedtime travelers. “Etaix and [coscreenwriter Jean-Claude] Carrière cram in a whole dormitory of delightful variations on the idea of beds as automobiles and dreamers as travelers,” writes David Cairns, who quotes the director recalling a story that inspired the sequence: “I had a friend who lived near a road with very heavy traffic who told me, ‘Every night when I go to bed, I feel like I’m driving a car.’ And that idea did something to me and led to the image of the beds on the roads. Oddly enough, funny ideas always come from something real.’ ”

Wild Strawberries

In Ingmar Bergman’s haunting exploration of aging, memory, and regret, Victor Sjöström plays a professor coming to terms with his mortality as he experiences a series of flashbacks to his childhood and family life. The nightmare that opens the film is marked by what scholar Mark Le Fanu calls a “sinister and mysterious righteousness.” It is in the dream sequences, he writes, “that most of the backstory is carried, and that the theme of guilt—guilt, as it were, for mere existence—is explored most profoundly.”

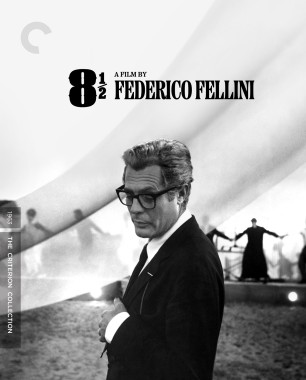

8½

Federico Fellini once referred to our romantic conception of cinema as “a dream we dreamt with our eyes open.” In his iconic film about filmmaking, 8½, dream sequences illustrate a director struggling with a creative block, a state of inner turmoil most famously captured in a scene that features Fellini’s alter ego, Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), stuck in a surreal traffic jam. As scholar Alexander Sesonske writes in his liner notes, “Fellini’s brilliance reaches beyond the surface to include an intricate structure of highly original, highly imaginative scenes whose conjunction creates an unprecedented interweaving of memories, fantasies, and dreams with the daily life of his hero.”