Walking with Scorsese

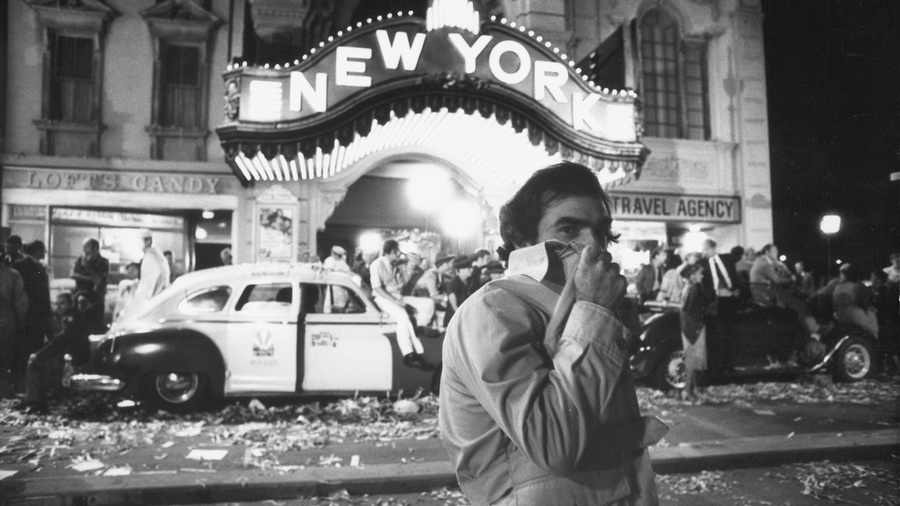

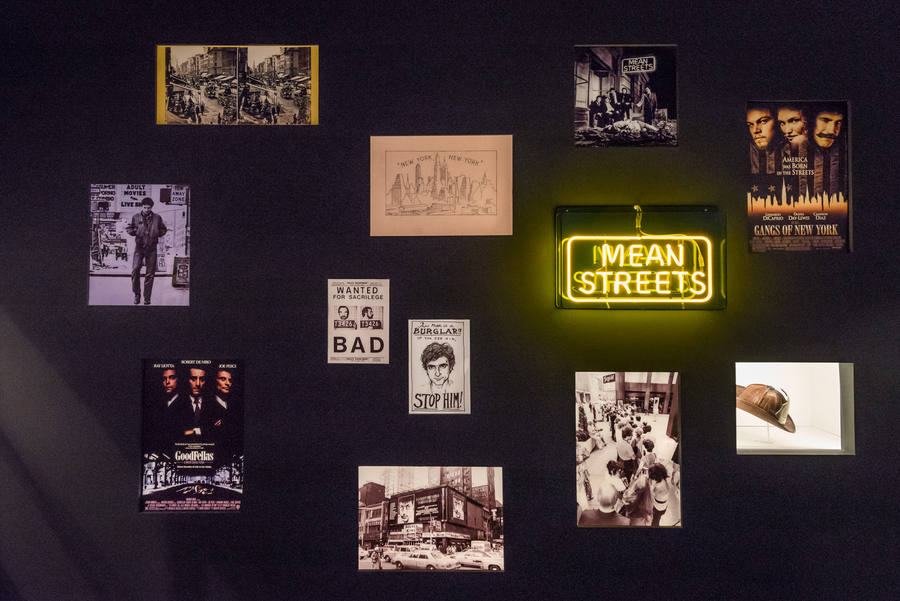

To the extent that such a thing is possible, I entered the Museum of the Moving Image’s Martin Scorsese exhibition the wrong way. The expansive showcase, which opened last December and continues through April 23, properly begins on the second floor of the Astoria, Queens–based institution, with a section on the filmmaker’s family and his childhood. Instead of starting there, I wandered around the first-floor area dedicated to Scorsese’s love for and use of music. The first thing I saw was a crate containing a collection of 45 rpm records that the director had acquired as a teenager in the midfifties, all meticulously indexed—including such songs as the Cellos’ “Rang Tang Ding Dong” and Mickey & Sylvia’s “Walking in the Rain.” Not far from it hung a small piece of paper with Scorsese’s notes for the music of his breakthrough feature, Mean Streets (1973): “Music as source and score,” he’d written, “as in my life” (emphasis his). All around me were artifacts relating to music and his career: pages from Bernard Herrmann’s handwritten score for Taxi Driver (1976), a list of songs for Shutter Island (2010), a gold record for the album of his concert documentary The Last Waltz (1978). This might have been, technically speaking, the end of the exhibition, but it was a great way to begin, with a burst of music and images of youth—not unlike the electrifying credit sequence of Mean Streets, which played on a monitor nearby.

The experience of walking through this entire exhibition is not unlike that of watching a Scorsese film: the rapid-fire barrage of information and images, of textures and sounds, seems to replicate his style. (So many materials clustered so close together can even have the effect of making you move through the exhibition faster, in an attempt to take it all in in one trip—thus also giving your visit the rhythm of one of his films.) There stands, as we enter the second floor, the Scorsese family dining room table, around which the director’s parents, Charles and Catherine, sat during the shooting of his touching family documentary Italianamerican (1974). Surrounding it is a wall of family photos, as well as pictures of his parents from the sets of productions like Goodfellas (1990) and The Age of Innocence (1993), in which they had memorable cameos.

Every Scorsese picture is an immersive maze of style, story, and character. This exhibition is no different, but the character is the director, and the way the show blends cinema and reality seems to be a comment on the way the filmmaker’s biography has been marked by a constant blurring of the boundaries between art and life. Not only has Scorsese often cast himself, his family, and his friends in his films, but you can also sense his thematic preoccupations—obsession, belonging, sacrifice, violence—running throughout his life. The wiseguys and crooks who strut and brood across the frames of his films are variations on the figures he’s met in the real world; so are the priests and self-negating loners. They are also, on some level, manifestations of himself: Scorsese clearly finds a personal connection to all his characters, even the basest ones. We love to talk about the violence and stylization in his films; we don’t talk enough about their empathy.

The exhibition, initially organized by Berlin’s Deutsche Kinemathek–Museum für Film und Fernsehen, was curated and designed by Kristina Jaspers and Nils Warnecke, who approached Scorsese five years ago with the idea. The director had to take some time to think about it—not just because a lot of the material would be personal artifacts, but also perhaps because he didn’t want to give the sense that his career was in any way at or near an end; his one condition for the curators was that the exhibit not be organized in linear fashion. (Later, addressing Melbourne’s Australian Centre for the Moving Image on the occasion of the exhibition’s opening there, Scorsese remarked, “It’s kind of odd, actually, seeing your whole life splayed out in front of you in all these different rooms, for better or worse . . . Even now, at age seventy-three, , we’re still discovering what cinema is or what it could be. There’s so much yet to do.”) Museum of the Moving Image chief curator David Schwartz says that originally, because it had been so hard getting Scorsese to say yes to the project in the first place, there was some doubt as to whether the exhibition would ever travel beyond Berlin. But eventually, with the director’s blessing, it made its way to Australia, as well as to Italy, France, Austria, Belgium—and eventually his hometown, where MoMI was a natural choice. “He’s been here a few times,” Schwartz recalls, “most memorably for a private 70 mm screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey for his daughter Francesca. He wanted her to see it the right way, so he had a print shipped and they came in on a weekend morning.”

Besides finding a way to fit the massive installation into a more modest space—MoMI is big, but it doesn’t have quite as much free exhibition space as other venues that have hosted this show—the museum also added some new materials, including a separate section featuring artifacts from Scorsese’s latest, Silence. Among these: concept sketches, storyboards, and props, including a small crucifix that plays a key role in the film. The Silence material is sparse and set apart from the main exhibition; the film was still in production when the show made its earlier stops. But looking at these pieces, you sense how much this somber drama set in medieval Japan fits within the rest of his oeuvre—from its lonely hero and immaculate period re-creations to its depiction of the mysteries of faith.

For anyone who has heard Scorsese discuss his nearly three-decade-long obsession with making Silence, one item feels like a real piece of history: the director’s own much-marked copy of Shusaku Endo’s 1966 novel, with an inscription from Paul Moore, the Episcopal bishop of New York, who famously gave it to Scorsese after the premiere of The Last Temptation of Christ. “Some of my favorite artifacts are the books that he’s marked up,” Schwartz observes. “We have a copy of Luc Sante’s Low Life [which was used as research for Gangs of New York] where there are Post-it notes on almost every page! You really get a sense of the way that Scorsese does research and how much he loves reading.” While it’s usually not possible to make out what’s written on these pieces of paper and in margins throughout the exhibition, the sheer volume of them makes it clear that Scorsese is constantly thinking and jotting down notes. I find myself imagining him reading a book the way some of his characters speak—quickly, aggressively, always catching the smallest details.

The director’s cinephilia understandably gets its own section, filled with posters for such Scorsese favorites as The Red Shoes and 8½ and props from his collection—including the bouquet of flowers used in Hitchcock’s Vertigo. In fact, cinephilia, not unlike New York, appears throughout the exhibition like an animating spirit. A dog-eared copy of Richard J. Anobile’s 1974 book on Hitchcock’s Psycho, which Scorsese consulted heavily during the making of 1980’s Raging Bull, appears in a section dedicated to editing. A note nearby in Scorsese’s own hand, dated 1981, explains how the director and his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker looked at the shower scene in Hitchcock’s masterpiece while creating the final fight between Jake LaMotta and Sugar Ray Robinson in their film, using it to guide both the rhythm of the cutting and the shot selections. Watching the two scenes side by side, you can see how Robinson’s punches recall Norman Bates’s jabbing knife, and how the simple image of blood dripping down a pair of bare legs can convey so much ferocity.