Shades of Gray

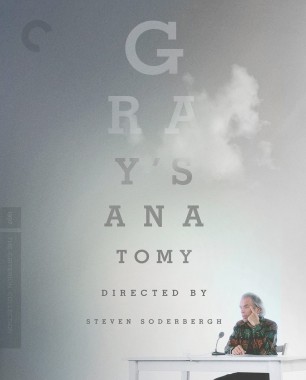

Tonight we salute the unique gifts of actor and monologue artist Spalding Gray, whose solo performance pieces inspired soaring flights of cinema like Jonathan Demme’s Swimming to Cambodia and the two Steven Soderbergh films that make up our double bill. Gray’s Anatomy is a razzle-dazzle remounting of Gray’s tour de farce about his fear of having minor surgery to correct a “macular pucker” in his left eye. And Everything is Going Fine is a stunningly empathic documentary about Gray’s life from his boyhood in Barrington, Rhode Island, to his final days in the Hamptons. In Gray’s Anatomy, Soderbergh toys with his offbeat star’s Spartan aesthetic. In And Everything Is Going Fine he celebrates it, creating one of the most moving tributes one artist has ever paid another: a Soderbergh movie that also functions as Gray’s posthumous masterwork.

Movie lovers coming fresh to Gray’s infinitely surprising, sometimes heartbreaking work—he would sit down at a table in front of a notebook or cards and just start talking, thoroughly uninhibitedly—should think of him like a fusion of André Gregory and Wallace Shawn from My Dinner With André. Like Gregory, he’s open to the most unnerving experiences, which in Gray’s Anatomy include praying for health in a New Age/Native American sweat lodge and submitting to a “psychic surgeon”—indeed, “the Elvis Presley of psychic surgeons”—in the Philippines. But Gray also has a Wally Shawn side that’s pragmatic and down-to-earth. (He finally does submit to surgery.) The tension between the two halves gives his performances their spring.

And Everything Is Going Fine illuminates every aspect of Gray’s multifaceted performances, and all his humanity, using extensive clips from his monologues and video interviews, as well as unused footage from Barbara Kopple’s documentary miniseries The Hamptons. Without any voiceover narration, Soderbergh balances impressions of Gray’s narcissism and insight, his kindness and meanness, while tracing the growth of his complex sensibility, starting when he was young, in a Christian Science household with a suicidal mother. Art became Gray’s lifeline, and when a terrible car accident injured his brain and diminished his creative capacity, that line was cut.

Gray was such a “born actor” everything funneled into his profession. He says he became “like an inverted Method Actor. I was using myself to play myself.” Soderbergh shapes ninety hours of footage into a seamless eighty-nine minutes. Here he explains how he conceived of this film as Gray’s “new monologue”—his last.