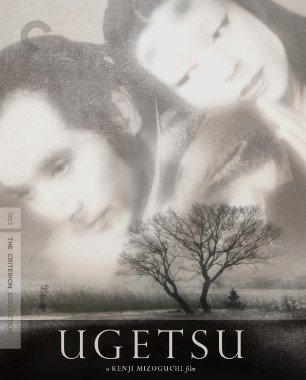

Often named as one of Japan’s three most important filmmakers (alongside Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu), Kenji Mizoguchi created a cinema rich in technical mastery and social commentary, specifically regarding the place of women in Japanese society. After an upbringing marked by poverty and abuse, Mizoguchi found solace in art, trying his hand at both oil painting and theater set design before, at the age of twenty-two in 1920, enrolling as an assistant director at Nikkatsu studios. By the midthirties, he had developed his craft by directing dozens of movies in a variety of genres, but he would later say that he didn’t consider his career to have truly begun until 1936, with the release of the companion films Osaka Elegy and Sisters of the Gion, about women both professionally and romantically trapped. Japanese film historian Donald Richie called Gion “one of the best Japanese films ever made.” Over the next decade, Mizoguchi made such wildly different tours de force as The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), The 47 Ronin (1941–42), and Women of the Night (1948), but not until 1952 did he break through internationally, with The Life of Oharu, a poignant tale of a woman’s downward spiral in an unforgiving society. That film paved the road to half a decade of major artistic and financial successes for Mizoguchi, including the masterful ghost story Ugetsu (1953) and the gut-wrenching drama Sansho the Bailiff (1954), both flaunting extraordinarily sophisticated compositions and camera movement. The last film Mizoguchi made before his death at age fifty-eight was Street of Shame (1956), a shattering exposé set in a bordello that directly led to the outlawing of prostitution in Japan. Few filmmakers can claim to have had such impact.