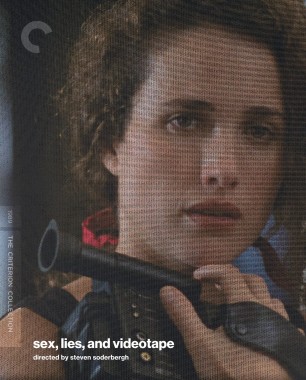

Sex, Lies, and Videotape

Every once in a while some outlaw comes along to prove that movies can be something else—not just a weary procession of prepackaged product, but a spectacular mode of personal expression. Steven Soderbergh is the prodigy of 1989 who came up with sex, lies, and videotape, a fascinating and low-budget exposé of some very strange modern relationships that won the Golden Palm (Best Film) and Best Actor award for James Spader at the Cannes Film Festival. It turned out to be one of the most successful and talked about films of the year.

Steven Soderbergh’s writing and direction are frighteningly accurate, and he is irreproachable in his love for his characters, all of whom are none too lovable. In this premiere display of his cinematic prowess he shows not just talent but a degree of personal honesty rarely visible in film. Paying little attention to civilized rules of cinema, and with a bit more than one million dollars, he has somehow expressed all his hidden anxieties, and it’s surprising how much wisdom he displays while letting each character deal with the unique quality of their misery. sex, lies, and videotape is an amazingly brave film, especially when you compare its sexual values against any other American movie. In most films, the characters have lives around which their sex lives revolve. But in sex, lies, and videotape, the characters have sex lives around which the rest of their lives revolve. It’s much closer to reality than most of us would like to admit.

Graham, Ann, John, and Cynthia, the four main characters, have got so many hang-ups that the film basically has no protagonist. There’s not a single character whose struggle we can endorse whole-heartedly. Are we really expected to identify with the woman who can’t have an orgasm, or her sleazy husband who has nothing but? Are we supposed to identify with the barmaid who is secretly undermining her sister’s marriage, or the guy who is only impotent in front of other people? Though these individuals are all fascinating, none of them are particularly appealing. We’re left with nothing to empathize with but the single thread they share in common, that life is a whirlpool of compromises, full of pain and unique surprises. You can walk out of this film feeling a little bit better about yourself; after all, if these people can work out their problems, your problems should be a snap.

The performances are all precise and masterful. As Graham, James Spader radiates benign neurosis. In his previous roles in Baby Boom, Less Than Zero, Wall Street, and the underrated Jack’s Back, he only scratched the surface of the vulnerability he displays here. Similarly, Peter Gallagher’s work in The Idolmaker, Summer Lovers, and the vastly underrated Dream Child didn’t ever approach the ruthless callousness he demonstrates as John.

But it’s the women who are the real surprises. Though her modeling career was thriving, Andie MacDowell was sure that her acting career was over, when her entire performance as Jane in Greystoke was redubbed by Glenn Close. But after her astoundingly complex performance as Ann, she won the L. A. Film Critics’ Award as the Best Actress of the year and immediately secured the leads in two more films. As her sister Cynthia, Laura San Giacomo oozes sex and sarcasm, a deadly combination. This is her first film, and with it she won the L. A. Film Critics’ Award for most promising newcomer, plus several lead roles.

The plot is laid out immediately through monologues, snappy guitar work, and incredibly clever editing. The marriage of John and Ann Millaney is based on lies, and Graham’s life is based on truth and videotape—which cannot lie.

Only in a world of AIDS could Graham’s problem make any sort of sense. There’s a peculiar sort of logic to a man who uses video instead of a rubber as a prophylactic against the plague of the decade, where any sexual encounter may be your last. He’s a sick puppy, and by the end, he actually starts mixing up the tenses in his sentences, confusing real time with videotape time.

Audio edits take place moments before or after visual edits, causing vocal overlaps that are curiously misleading. We hear Ann’s voice say, “Can I tell you something personal?” while we’re looking at her sister make love to her husband. For one brief moment, it seems like Cynthia talking, but then the film cuts to Ann in a restaurant with Graham, and we realized we’ve been tricked.

This isn’t a mistake, but a stylistic idiosyncrasy from a man in total control of his artform. “You go through three phases trying to express yourself in any art form” explains Soderbergh. “First, you imitate. Next, you begin to document what you’re thinking and feeling and use the crafts you’ve learned through imitation. Then there’s the third phase: taking the emotions and feelings you’ve experienced—which are autobiographical—and creating a fictional story with which to express them. That was the big leap for me, because emotionally, sex, lies, and videotape is very autobiographical, and yet nothing in the film actually occurred. And by being fictional I was able to be clearer in what I was trying to get across.”

What Soderbergh gets across in sex, lies, and videotape is relationships that are naturalistic and entirely believable, not to mention entertaining. He’s also remarkably perceptive for someone only 26 years old. How can Soderbergh already have such a deep understanding of human nature and obsessive behavior? It takes a peculiar sort of mind to come up with characters this uniquely unhealthy. This is a film that should have been made by Nicholas Roeg or Eric Rohmer, some wise old foreign craftsman looking back on his personal life with years of perspective. Either sex, lies, and videotape is a fluke and Soderbergh is madman, or we’ve got a lot of interesting movies to look forward to from his overripe brain.