The Blob

The Blob on laserdisc? Oh, come on. Isn’t it just a ‘50s, black and white, small screen, cheesy horror flick? Wrong. If you only saw The Blob twenty years ago on your parents’ old Zenith, you’re in for a surprise. The Blob is widescreen, The Blob is in color, and The Blob is a hoot. It is the only movie ever made where the first thing you have to do in order to sing the theme song is stick your finger in your mouth, blow, and make a popping sound while plucking it out of your cheek. It’s also the only film in which Steve McQueen is billed as Steven McQueen, and it’s the only movie in which he plays someone named Steve. But more important, The Blob is the definitive ‘50s film about a town that won’t listen to the kids until it’s too late.

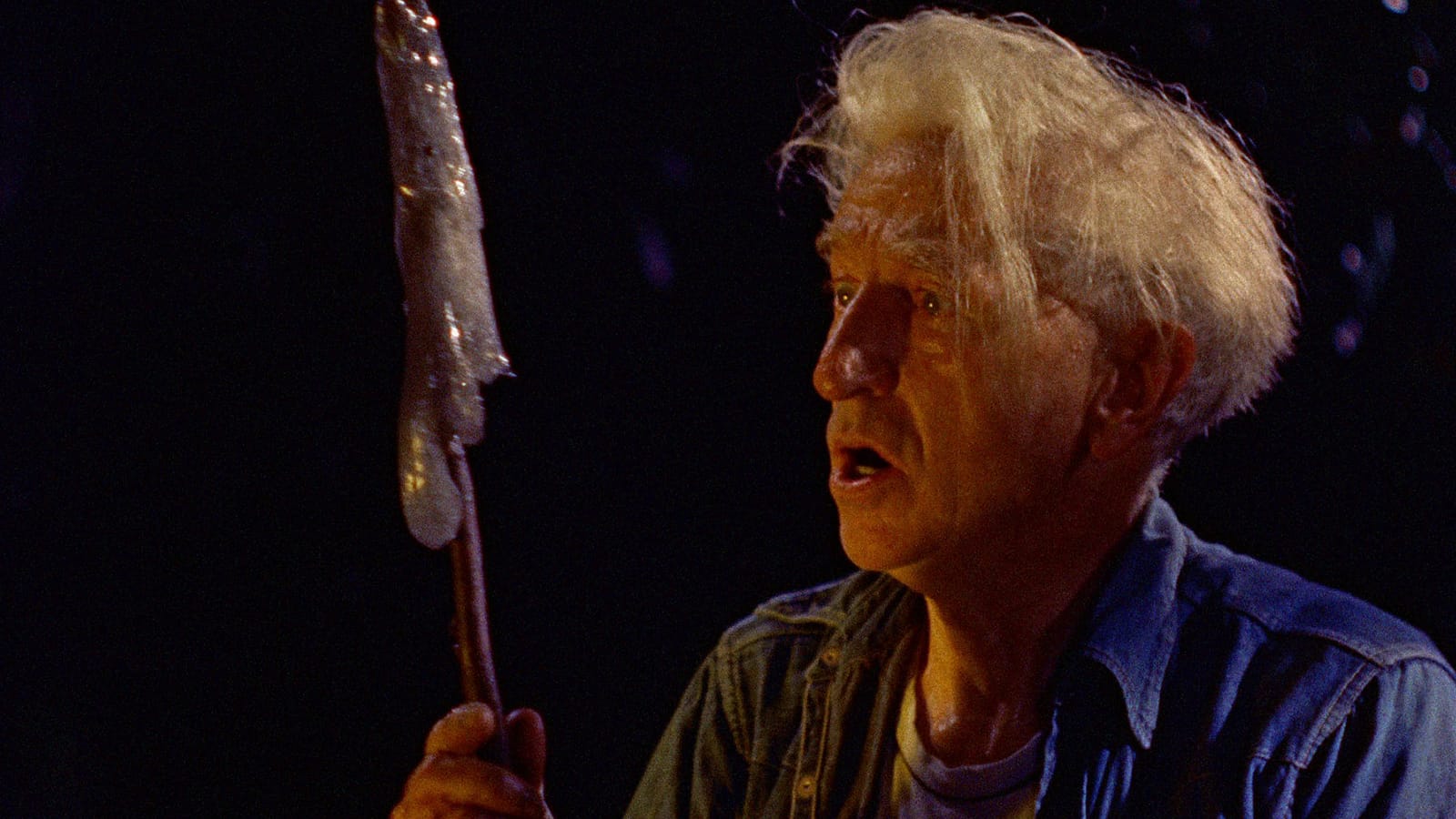

It takes place on one night in one town—almost in real time. At the start of the story, The Blob is out there “hot-rodding around the universe” when it crashes to earth. An old man finds it in a ditch and doesn’t know what it is (even though everyone knows that a meteorite looks like a bowling ball covered with teeny craters). He pokes it with a stick, it cracks open, and soon the hills are alive with the sound of mucus as the hungry raspberry jelly from across the universe starts assimilating the flesh of all who dare to draw near.

Steve and Jane (Aneta Corseaut, who later appeared as Andy’s girlfriend on The Andy Griffith Show) are two teenagers out necking who follow the trail of a shooting star till they discover the horrible truth. Soon, the immortal line is spoken, “We’ll go to the police. They’ll know what to do.” Sure they will. Police academy training includes how to deal with killer gelatinous protoplasms, doesn’t it? What follows is a quaint portrait of teens vs. adults in Anytown, U.S.A., a portrait that immediately entered the annals of clichedom.

Though it was an immediate hit, it took fourteen years for there to be a sequel, Beware! The Blob (directed by Larry Hagman), and another thirty years for a remake (which wasn’t nearly as good). It also spawned dozens of oozing imitators, all the way from The H-Man, an Oriental version of The Blob, to Larry Cohen’s recent The Stuff.

Aside from its reasonable amount of tacky thrills, The Blob is best remembered as the film that gave Steve McQueen his first starring role. He expressed indifference towards a project in which he got to play a teenager at the age of 27, and where “the main acting challenge was running around bug-eyed, shouting, ‘Hey everybody, look out for The Blob!’ I wasn’t too thrilled when people would tell me what a fine job I’d done in it.” McQueen secretly wished the film would never see the light of day. He made only $3,000, preferring to get his payment in cash rather than in profit participation. Bad move. The Blob grossed 30 times its original investment. By the time The Blob was actually released, Wanted—Dead or Alive had just come on the air, and McQueen was well on his way to being a genuine star. In any case, his image as an intense loner, lover, and reluctant hero started here.

The Blob seems made by people unfamiliar with other horror films of the day. What was the matter with those screenwriters, Ted Simonson and Kate Phillips? What were they doing giving actual psychological motivation to so many characters? Steve isn’t just a wild reckless macho hotshot out to score with Jane in the back seat, he’s sincere and brave, with everyone’s best interests at heart. Officer Jim isn’t just a dumb cop who hates teenagers, he’s a dumb cop who hates teenagers because “one smacked into his wife on the turnpike.” Jane’s father isn’t just a concerned parent, he’s a high school principal who is worried about it “getting all over town.” (Not The Blob, but the fact that his daughter spent an hour in a police station.) Didn’t Simonson and Phillips know that they were dealing with a genre where everyone is supposed to be a cliché? These characters became stereotypes, but at the time they were miracles of depth.

In many other ways, you have to picture the time of the film’s original release to understand why audiences went bonkers. The scene where The Blob oozes out of the projection booth at the midnight spookie show would have been particularly effective at the time, since the audience in the theater on the screen would have perfectly mirrored the audience in the actual theater.

Of course the original critics didn’t see it that way. “A lethal lump of intergalactic plum preserves” declared one critical grump of his day, and “a crawling roomful of jello that eats you instead of the other way around” said another. Cue magazine blasted the film for promoting emotionally disturbed kids, Arthur Knight said it was “not so much horror as horrid,” and most other reviews were equally disdainful. Only the New York Herald Tribune went overboard in the other direction, calling it “a minor classic in its field.”

The director, Irvin S. Yeaworth, Jr., was a minister in the small town of Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, where the film was shot. Yeaworth built his special effects in a room of the church building, where, presumably, God oversaw the disappearance of matte lines. At many points in the finished film, The Blob is blatantly oozing on top of photographs of the previous scene. During the shuddering climax, The Blob gurgles its way over what looks like a postcard of the Downingtown Diner (the only diner on earth with a basement). I guess God let Yeaworth down. He (Yeaworth, not God) eventually went on to make The 4-D Man and Dinosaurus, about which the less said the better.

Producer Jack H. Harris, who also made John Landis’ Schlock and John Carpenter’s Dark Star, put up $150,000 of his own money to make The Blob (working title: The Molten Meteor)—an investment that was immediately doubled when Paramount picked up the completed film for $300,000. (Eventually, the rights reverted back to Harris, who reissued the film many times himself.) Paramount then spent another $300,000 on an ad campaign that was so effective, the film brought in $1.5 million in rentals in just one month.

This was particularly amazing considering the fact that The Blob was released at the height of a low-rent horror film craze. The screens of America were virtually inundated with bug-eyed monsters conjured up from the mysterious secrets of the new nuclear age. Fans of subtext can rationalize that The Blob was an allegory of the public’s sincere anxiety about the scientific unknown. The rest of us can just sing along with the theme song. Ready now? Okay, stick your finger in your mouth . . . .