Black Narcissus

When Black Narcissus opened in England in 1947, Great Britain was barely emerging from the agony and exhaustion of World War II. Nothing could be further from gray, hungry postwar London than the India imagined by director Michael Powell and screenwriter Emeric Pressburger: here was a land of high mountains, lush forests, and fields of flowers exploding in deeply saturated Technicolor, a tempting landscape of overwhelming plenty.

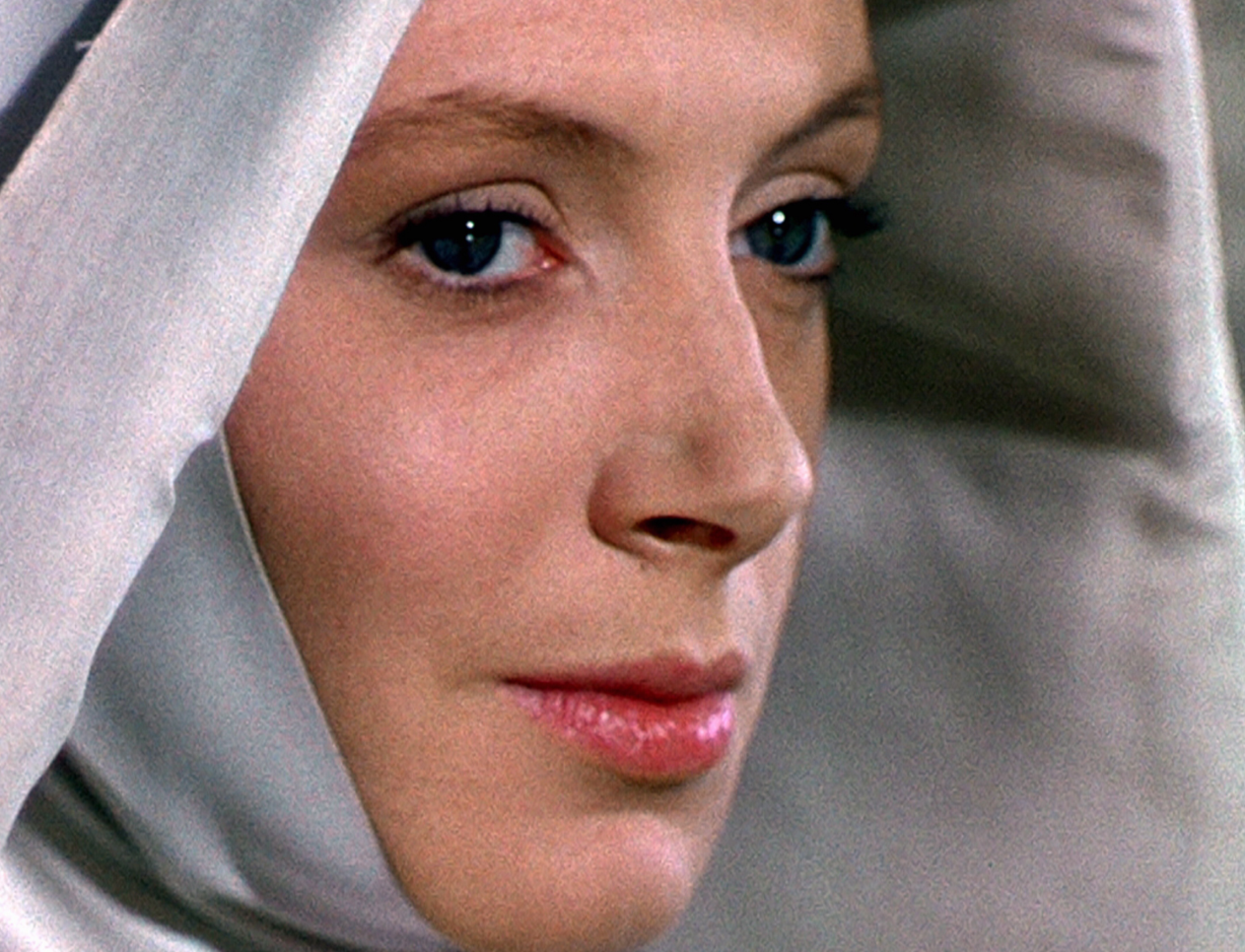

The film, based on a 1939 novel by Rumer Godden, follows a group of British nuns, the Servants of Mary, as they attempt to transform the former palace of a Hindu potentate into a dispensary and school for the local children. But the palace, perched on a mountaintop eight thousand feet above sea level, resists the transformation; once the site of joyously sensual feasts and orgies, the old palace exerts its influence over the sisters, and particularly over Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr), the group’s leader, who finds herself dreaming of the young man she left back in Scotland. Less innocently romantic are the reveries of Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron), who becomes erotically obsessed with the British overseer of the district, Mr. Dean (David Farrar).

There is little surface action in Pressburger’s script. Characters come and go, including an impossibly beautiful Jean Simmons, as a ripe 17-year-old bride who has been repudiated by her husband, and Sabu—the Indian child actor who was a mainstay of British movies about the Raj—as a local princeling who forces his way into the school. The “Black Narcissus” of the title turns out to be not some elevated poetic allusion but the name of the pungent aftershave with which the prince perfumes himself—a product he imports from England.

But if there is little action on the surface, emotions are seething just beneath it—or, more accurately, just behind it, in the form of the fantasy landscape that Powell and his collaborators have created out of purely cinematic means. Despite its dazzling visual sweep, not one frame of Black Narcissus was filmed on location. Instead, the film was shot at the Pinewood studios in suburban London, with a few day trips to an Indian garden in Sussex. The mountains and the castle are the creations of production designer Alfred Junge, with matte paintings executed by Peter Ellenshaw; the special effects were coordinated by W. Percy Day, who had apprenticed with Melies, and the magnificent color photography, surely among the finest work ever produced for the medium, is the contribution of Jack Cardiff. (Both Junge and Cardiff won Oscars for their work.)

Powell builds Black Narcissus as a series of moods created through space and color. He contrasts the boxy interiors and blank walls of the British colonial offices with the curved, multi-leveled, spatially indefinite chambers of the old palace. British certainty and sterility cedes more and more to Eastern mysticism and sensuality; the sister in charge of the vegetable garden can’t help but plant a crop of flowers instead, their exploding primary colors providing a dizzying contrast with the black and white habits of the nuns. Gentle, green hillsides—reminiscent of the Scottish landscapes we see in Sister Clodagh’s flashbacks—suddenly turn into vertiginous canyons when viewed from another angle. The ground literally opens beneath the feet of the characters, inviting them to take the plunge—to abandon their twin faiths, in God and the British Empire, and turn themselves over to more ancient and dangerous powers.

For Powell, who had always placed great value on music in his work, Black Narcissus is perhaps his breakthrough to a musical conception of the medium (his next film would be The Red Shoes). Despite the great wit and character of Pressburger’s dialogue, Black Narcissus is a film that develops almost entirely through formal rather than dramatic means. The carefully developed tensions between monochrome and color, between closed, coherent spaces and aching, cosmic voids, reach a crescendo in the bravura climactic sequence. It is enough to see the bright, red lipstick that Sister Ruth has put on to know that the apocalypse is near.

British audiences in 1947 may well have seen Black Narcissus as a last farewell to their fading empire. World War II had altered colonial relations forever; in its wake, nationalist movements would grow and British authority would collapse. India achieved independence on August 14, 1947, and the final images of Black Narcissus, of a procession down from the mountaintop, seem to anticipate the British departure. For Powell and Pressburger, these are not images of defeat, but of a respectful, rational retreat from something that England never owned and never understood. It is the tribute paid by west to east, full of fear and gratitude.