Cinema as Craft and Hunger

Richard Linklater has had a terrific week. On Tuesday, the BAFTA nominations were unveiled, including one for Ethan Hawke for his lead performance in Blue Moon, and on Wednesday, we learned that Linklater’s Nouvelle Vague is leading the nominations for the César Awards. Then, on Thursday, the Library of Congress presented this year’s list of the twenty-five films added to the National Film Registry, and Linklater’s Before Sunrise (1995) is one of them.

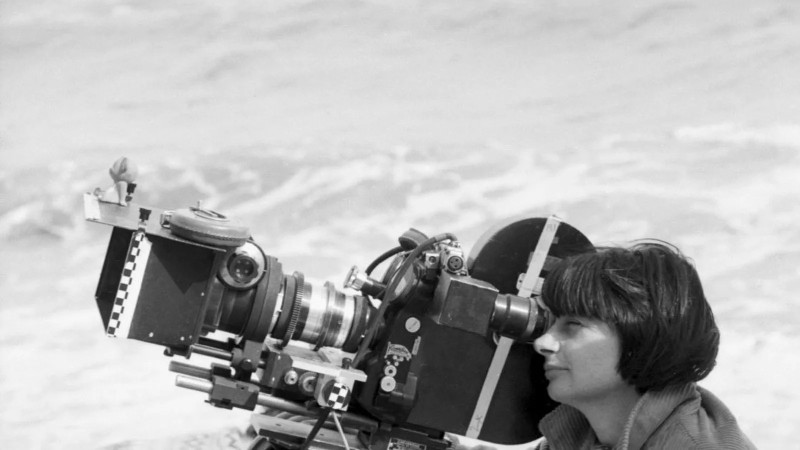

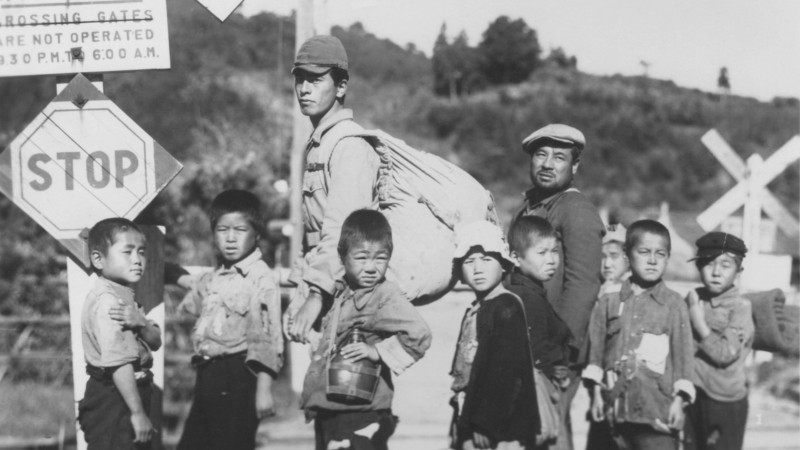

- Travel Companions, a ten-film series of works by Iranian directors Bahram Beyzaie (Bashu, the Little Stranger) and Amir Naderi (The Runner), opens today at Metrograph in New York. “To place Beyzaie and Naderi side by side is not to pose a rivalry, but to honor two esteemed auteurs and two orientations about what cinema can do,” writes Arta Barzanji in Metrograph’s Journal. Beyzaie, who passed away last month, is “considered a defining modern playwright and theater director as much as a director of features: a scholar of performance traditions, myth, and ritual whose films often feel like staged debates with cultural memory.” Naderi is “a filmmaker shaped by the southern port cities where he grew up, raised by his aunt; by movie theaters; by watching and laboring; by learning cinema as craft and hunger.”

- This evening at MoMA, Scott Eyman, whose latest book is Joan Crawford: A Woman’s Face, will introduce a screening of Robert Aldrich’s Autumn Leaves (1956) after Casey LaLonde, Crawford’s grandson, presents his collection of home movies shot by the Hollywood legend from 1939 to 1944. “A year before Autumn Leaves was released,” writes Melissa Anderson at 4Columns, “Jacques Rivette, writing in Cahiers du cinéma, hailed Aldrich as a filmmaker who ‘achieves harmony through a precise dissonance.’ Discordance, not only in the age gap between Milly and Burt but also in the acting styles of Crawford and [Cliff] Robertson, animates and deepens what might otherwise be dismissed as a tawdry tearjerker.”

- Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason is nearly always working on more than one film at time, and he began shooting his latest, The Love That Remains, before commencing work on Godland (2022). Anna (Saga Garðarsdöttir), an artist, and Magnús (Sverrir Gudnason), a fisherman, are in the midst of a slow-motion separation, but Magnús keeps hanging around the house with their three kids. At Reverse Shot, Michael Koresky observes that Pálmason “seems to take enormous pleasure in showing us familiar things in unfamiliar ways: domestic dramas are a dime a dozen, yet it’s unlikely you’ve seen—or felt—one quite like this. Pálmason’s instincts for composition, cutting, and the shaping of cinematic space are constantly unusual without ever seeming willfully idiosyncratic.”

- “By rolling the teen, party, urban, Black, and coming-of-age movie into one,” writes Robert Daniels for Letterboxd, Reginald Hudlin’s House Party (1990) “crafted a framework that influenced countless filmmakers who hoped to make a movie about teenagers enjoying the night of their lives.” At IndieWire, Jim Hemphill notes that House Party is “naturalistic and slightly heightened and theatrical, anchored in reality but stylized and charged with as much visual and aural energy as any classic MGM musical.” Both Daniels and Hemphill point out that the film’s critical and box-office success—earning back its $2.5 million budget ten times over—opened doors for other Black filmmakers, making the 1990s what Hemphill calls “the best decade ever for Black cinema when it comes to breadth, depth, and volume.”

- Lukas Brasiskis, Curator of Film & Video at e-flux, recalls the late Béla Tarr looking back on an encounter with another filmmaker who told him after the premiere of Damnation (1988) that “he should learn how ‘to tell a story’ if he ever wanted to become a true director.” Tarr’s reply: “I don’t want to be a film director. ‘Truly, I never wanted to,’ he told me. ‘And would rather not have become one, but it was the only language I had to speak in.’ I took this anecdote as a rhetorical move in a familiar dispute about different conceptions of film narrative. Years later now, it seems to me more like a principle—a counter-model to the transactional logic that dominates film- and art-making today.”