The Last Picture Show

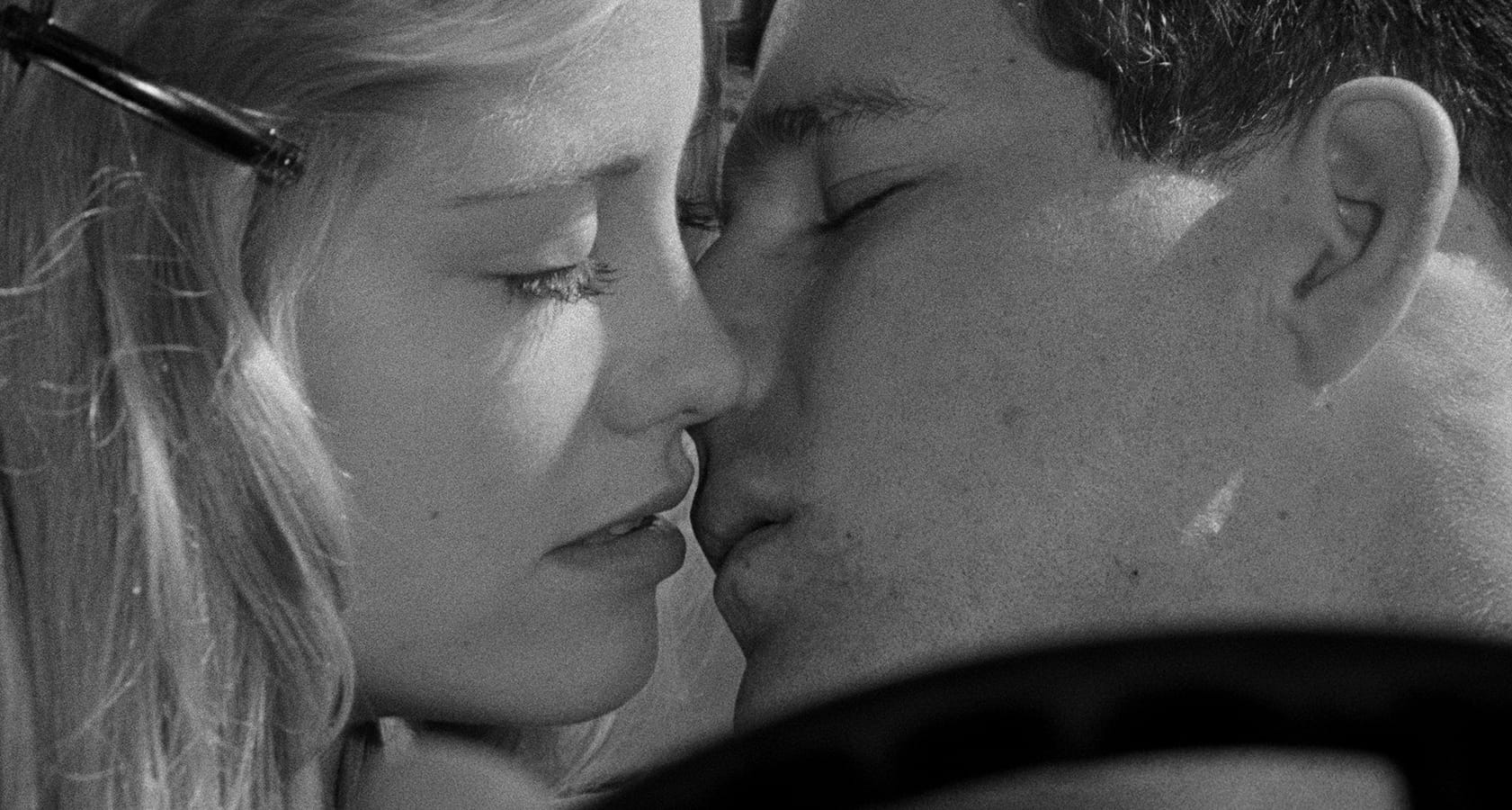

On its twentieth anniversary, Peter Bogdanovich’s critically-acclaimed, prize-winning piece is even more impressive thanks to the restoration of seven minutes of additional footage including a crucial sequence (a pool table seduction of Cybill Shepherd) that was deleted before the picture’s release. Bogdanovich doesn’t consider this improved director’s version to be merely a restoration of a landmark film from the 1970s, but something completely new: “the 1990s version of The Last Picture Show.”

For only his second studio film—Bogdanovich made the excellent, but little seen, Targets, in 1968—the former film critic chanced directing an adaptation of Larry McMurtry’s elegiac novel about teenagers who come of age in a dying Texas town in the early fifties. It was such an unlikely project for a successful movie that it took first-time producer Stephen J. Friedman two years to get financing, with tiny BBS Productions taking the gamble. Bogdanovich himself was in a gambling mood, eschewing stars for charismatic young newcomers Timothy Bottoms, Jeff Bridges, Randy Quaid, and his discovery, Cybill Shepherd, and marvelous character actors, Ben Johnson, Cloris Leachman, Clu Gulager, Eileen Brennan, and Ellen Burstyn. Even more daring was his decision to make the film in black-and-white. Bogdanovich’s choices paid off. The unknown cast turned in exceptional individual performances and worked brilliantly as an ensemble: Bottoms, Bridges, and Shepherd quickly became stars, Johnson and Leachman won Best Supporting Actor and Actress Oscars, and Burstyn was voted Best Supporting Actress by the New York Film Critics, paving her way to stardom.

Appreciative audiences and critics thought it most appropriate that a dying art form should be used to visualize a dying town, a dying era, and a dying way of life. Bogdanovich: “I saw the story as a Texas version of Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, which was about the end of a way of life caused by the coming of the automobile. This was about the end of a way of life caused by the coming of television.”

Even at the film’s beginning, Anarene, Texas (filming actually took place in Archer City) is already much like a ghost town or graveyard, with constant wind and dust swirling on the empty streets and into the nearly empty small business establishments. Ultimately the only movie house in town will close down (after showing Red River)—all movie fans will share the sense of loss felt by long-time customers Bottoms and Bridges—and the film’s oldest and youngest characters will be dead. Indeed, the decline of the town, which Bogdanovich effectively uses as one of his central characters, is emblematic of the personal declines, deaths, and departures of its populace. Our pivotal teenager characters, the sensitive Bottoms, best friend Bridges, and rich-bitch Shepherd, who comes between the boys for a time, may each lose their virginity, but they are so unfulfilled and confused that their rites of passage signal more the death of youth and innocence than a new-born maturity. Growing up doesn’t seem like such a good prospect to these teenagers when all the adults in town are miserable. Pauline Kael affectionately wrote: “Concerned with adolescent experience seen in terms of flatlands anomie—loneliness, ignorance about sex, confusion about one’s aims in life—the movie has a basic decency of feeling, with people relating to one another, sometimes on very simple levels, and becoming miserable when they can’t relate.”

With a script by Bogdanovich and McMurtry that won the New York Film Critics award, The Last Picture Show is a strange cross between Hud (based on McMurtry’s Horseman, Pass By) and Peyton Place. The intertwining relationships, friction between youths and adults, impulsive actions, confused teenagers, manipulative females, feuds, scandals, affairs, first-time and other sneaky sex make it ideal material for an adult soap. Interestingly, a less sensitive director than Bogdanovich could have made an exploitation film using the same script. But it wasn’t his intention to dwell on the sordid goings-on in Anarene, though he’ll let us eagerly follow Shepherd into a motel room with Bridges and to a nude swimming pool party. He was more interested in creating an authentic small-town Texas milieu, by paying special attention to the decor of the various establishments: the country music that constantly plays on the radio, and the manners, quirks, dress and hairstyles of his characters. You really believe that the people who populate the screen have lived in Anarene all their lives. Bogdanovich was equally successful at establishing fascinating relationships between various troubled characters, male and female, young and old. I think that the “romance” between Bottoms and the older, unhappily married Leachman, who gives an astonishing performance, is unlike anything else in cinema.

It’s true that much of Bogdanovich’s subject matter is depressing. Yet with Hank Williams on the soundtrack, exciting talent playing real characters up on the screen, unexpected humor, and Robert Surtees’ lovely black-and-white cinematography sending us back in time, we hardly notice.