Deep Crimson: Blood Will Have Blood

Arturo Ripstein’s six-decade-long career has been guided by a fearless iconoclasm and a dark gift for transforming popular genres—the western, the family film, and, above all, the melodrama—into sharp weapons to attack the prejudice and myopia deeply rooted in Mexican history. Yet, while his major films deliver swift, cutting blows to patriarchy, provincialism, and machismo, their power and artistry go beyond their daring themes. Within Ripstein’s stark, mesmerizing imagery lurks a strange fusion of beauty and brutality, compassion and violence, permeating his entire oeuvre with a profound melancholia and a sense of slow, inexorable decline. The unyielding pessimism found in Ripstein’s work is counterbalanced by a bracing humanism—an empathetic fascination with the secret nightmares and fantasies of his antiheroes, whose weakness, hubris, and folly he refuses to sentimentalize.

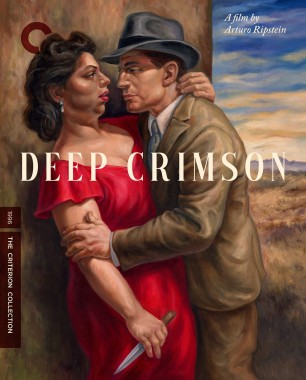

Though early on in his career he solidified his reputation as a risk-taking auteur in Mexico and the rest of the Spanish-speaking world, Ripstein’s twentieth feature, Deep Crimson (1996), was his first to receive wider international acclaim. The film’s success, particularly in the United States, can partly be attributed to its unbelievably true and quintessentially American source: the tale of the “Lonely Hearts” killers, a couple who swindled and murdered hapless widows in the late 1940s and, decades later, inspired Leonard Kastle’s now-classic independent film The Honeymoon Killers (1969). Ripstein transposes the grisly events to remote northern Mexico, makes expressive use of the vast, lonely Sonoran landscapes, and references touchstones of studio cinema, which loomed large in his upbringing as the son of Alfredo Ripstein, a prominent producer who was instrumental in modernizing the Mexican film industry during the forties and fifties. Despite its often grim tone, Deep Crimson offers an affectionate valentine to the romantic illusionism that flourished in that bygone era when cinema was both a popular and a populist art form.

Inspired by his regular childhood visits to his father’s studio, where he observed veteran filmmakers at work, Ripstein began his cinematic life at a precocious age. The director who exerted the deepest influence on him during his formative years was his father’s close friend Luis Buñuel. The Spanish surrealist, exiled in Mexico since 1946, became a longtime mentor and allowed the aspiring cineaste to observe the production of The Exterminating Angel (1962), one of the great works of the maestro’s fertile Mexican period. The lessons that Ripstein learned from Buñuel are clearly legible in the younger director’s extraordinary breakthrough, The Castle of Purity (1972), which anticipates Deep Crimson with its creative adaptation of a stranger-than-fiction true crime committed by a man who imprisoned his family for eighteen years in their Mexico City home. Played with fervent conviction by Buñuel regular Claudio Brook, the film’s troubled protagonist brings to mind today’s conspiracy theorists; he is maniacally fixated on exterminating the local rat population, enlisting his children to fabricate “artisanal” poison, and he also idolizes Nostradamus, whose proclamations he preaches as lessons to his wife and homeschooled offspring. While loosely reminiscent of the absurd and enigmatic confinement of the dinner guests in The Exterminating Angel, the family’s physical and psychosexual captivity in The Castle of Purity predicts a unifying theme in Ripstein’s major films: the idea of human desire as a dangerously enchanting, claustrophobic fantasy realm capable of ensnaring and ultimately destroying those who dare enter.