Five NYFF Highlights

The Pordenone Silent Film Festival opens tomorrow, and festivals are on in Mill Valley and Vancouver. The talk of every town, in the meantime, is Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another, now heading into its second weekend. Actual talk: One Battle is Topic A on the latest episodes of such podcasts as Cannonball with Wesley Morris, Slate’s Culture Gabfest, and the Ringer’s Big Picture.

- In Ulrich Köhler’s Gavagai, Caroline (Nathalie Richard), a French director, shoots a contemporary reinterpretation of Medea in Senegal. Her lead actors, Nourou (Jean-Christophe Folly) and Maja (Maren Eggert), are having an affair, and months later, at the premiere of Medea in Berlin, Maja steps up to defend Nourou when he’s racially profiled at a swanky hotel. A. G. Sims’s review for Reverse Shot is excellent, but don’t miss Mark Peranson’s Notebook interview with Köhler. “Becoming aware of our biases and potential for misunderstanding will improve human relations,” says Köhler, “but I’m not even sure of that. No, it’s not a message movie, that’s for sure. It’s just depicting how complicated human interaction is. And more concretely, it’s that the question of racial bias is not easily resolved by good intentions, and that we have to be aware that by trying to do something good, we can make things worse, quite easily.”

- Köhler denies that Caroline is based on Claire Denis, as many have assumed. In The Fence, Denis’s adaptation of a play by Bernard-Marie Koltès, a West African (Isaach De Bankolé) appears outside a white-run construction site and demands the release of the body of his brother, who has died in a work-related accident. “Her worst feature and it’s not even close,” declares Filmmaker’s Vadim Rizov, while for Guy Lodge at Variety, this is “an unusually sharp-cornered and rhetorical work from this typically elliptical and sensuous filmmaker”—but there is “rage swelling beneath its still, mannered surface.” At Little White Lies, Mark Asch writes that the play is “a frustrating and counterintuitive choice of source material for a filmmaker such as Denis, whose cinema is so elliptical, so mysteriously true to the lived sensual experience of confusing power dynamics. Her greatest and most beguiling films can sound, on the page, bald-faced and almost insultingly banal; the challenge when writing about, say, Beau travail is to convey how a simple thesis, about how masculinity and empire sublimate taboo desire into rituals of domination, can feel so quicksilver, heedless, and immersive on-screen.”

- Anemone may be a “modest movie,” as Manohla Dargis puts it in the New York Times, but the return of Daniel Day-Lewis eight years after he announced his retirement is a very big deal. He plays an English hermit far from pleased to be reunited with his estranged brother (Sean Bean), and Day-Lewis cowrote the screenplay with his son Ronan, who directs. It’s simply great to hear from the grand old actor again, whether he’s talking with the NYT’s Kyle Buchanan or Rolling Stone’s David Fear, who calls Anemone “an intense, joyous, sorrowful, and sometimes absurd family drama that occasionally veers into the sort of strange, hyperreal territory that involves giant fish, freak hail flurries, and an elongated, camel-like creature with a human face and a tiny penis.”

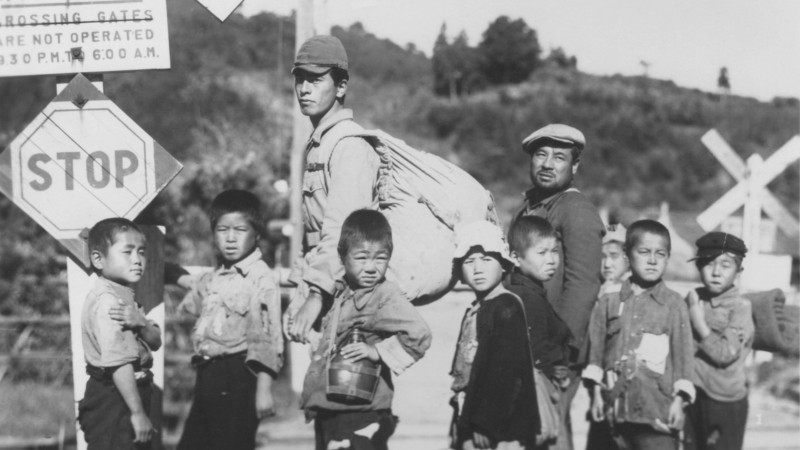

- For his new feature, Kamal Aljafari (A Fidai Film) has done very little tweaking on the recently rediscovered footage he shot on a MiniDV camera while traveling through Gaza in 2001 with a guide, Hasan Elboubou. With Hasan in Gaza “possesses a tremendous and at times unbearable force, given that the world it depicts has since been destroyed by Israel and its international supporters,” writes Erika Balsom for the New Left Review. “The film exists across a chasm, torn between the moment in which the images were captured and the moment in which they are being presented, throwing into painful relief the relation to time and finitude at stake in all photographic images. ‘This is the university,’ Hasan says; no more. Where are all the young people seen in the film now? Where is Hasan? The whole city of Khan Younis, where a long passage takes place, has been razed. Against all these crimes of extermination, every second of this documentary is an archive of presence, demanding recognition and remembrance.”

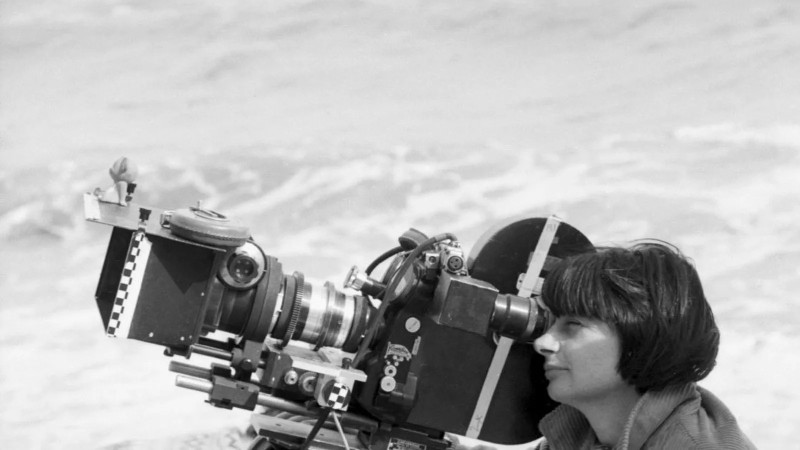

- Mary Stephen is an editor best known for her yearslong collaboration with Eric Rohmer. The new restoration of her debut feature, Shades of Silk (1978), premieres tomorrow, and the film, tracing the relationship between two Chinese women in Shanghai in 1935, “remains a tour de force of form, style, and historical imagination,” writes the New Yorker’s Richard Brody. “There’s something timeless about Shades: it’s anchored in the mid-1930s, it shows the ’20s, it was made in 1978; it harmonizes stylistically with several masterworks of its own time but is so evocative of the past and so aesthetically and thematically advanced that it seems to inhabit a zone outside chronology. It is as if the film is somehow displaced and distant from itself.” The retrospective Between East and West: The Cinema of Mary Stephen opens at Metrograph today, and Michelle Carey interviews Stephen for Metrograph Journal.