Wes Anderson’s Impossible Dreams

Wes Anderson was just twenty-six years old when his first feature film came out, but one might be forgiven for thinking he was even younger. Part friendship comedy, part road movie, part romance, and part crime caper, Bottle Rocket (1996) is a low-budget wonder touched by such a magic sense of play that it feels like it could have been made by a uniquely precocious child. At the same time, the film has a laid-back wistfulness that marks it as the work of someone wise beyond his years. That sounds like a contradiction, but it really isn’t. The two best friends at Bottle Rocket’s center (portrayed in an inspired bit of casting by brothers Owen and Luke Wilson, thus turning all the latent sibling rivalry of real life into cinematic subtext) may be in their twenties, but one reads as quite a bit younger, the other as older: Dignan (Owen) fancies himself becoming something of an outlaw, looking to land a big score—the way an impressionable younger boy might imagine his grown-up future—while the mild-mannered Anthony (Luke) has just gotten out of a mental institution into which he checked himself to deal with “exhaustion” and, it seems, general existential despair. Anthony might be a few steps ahead of Dignan in the growing-up department, but both men are fully out of step with the world, each in his own way.

This is the vital duality that animates Anderson’s work, and it becomes clearer across the ten features he made over his first twenty-five years as a filmmaker. It has been said that, in the director’s films, the grown-ups act like kids and the kids act like grown-ups. He understands what it means to want to get on with our lives, to discover all the wonder and adventure that is promised us when we are young; but he also sees the disillusionment that awaits on the other side, which in turn prompts a desire to regress, to return to that moment when a future full of magic still felt possible. He has continued to explore these two states of mind over the course of his career—and as he himself has gotten older, and the world around him has changed, his films have shifted in remarkable ways.

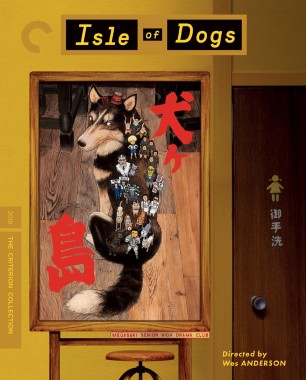

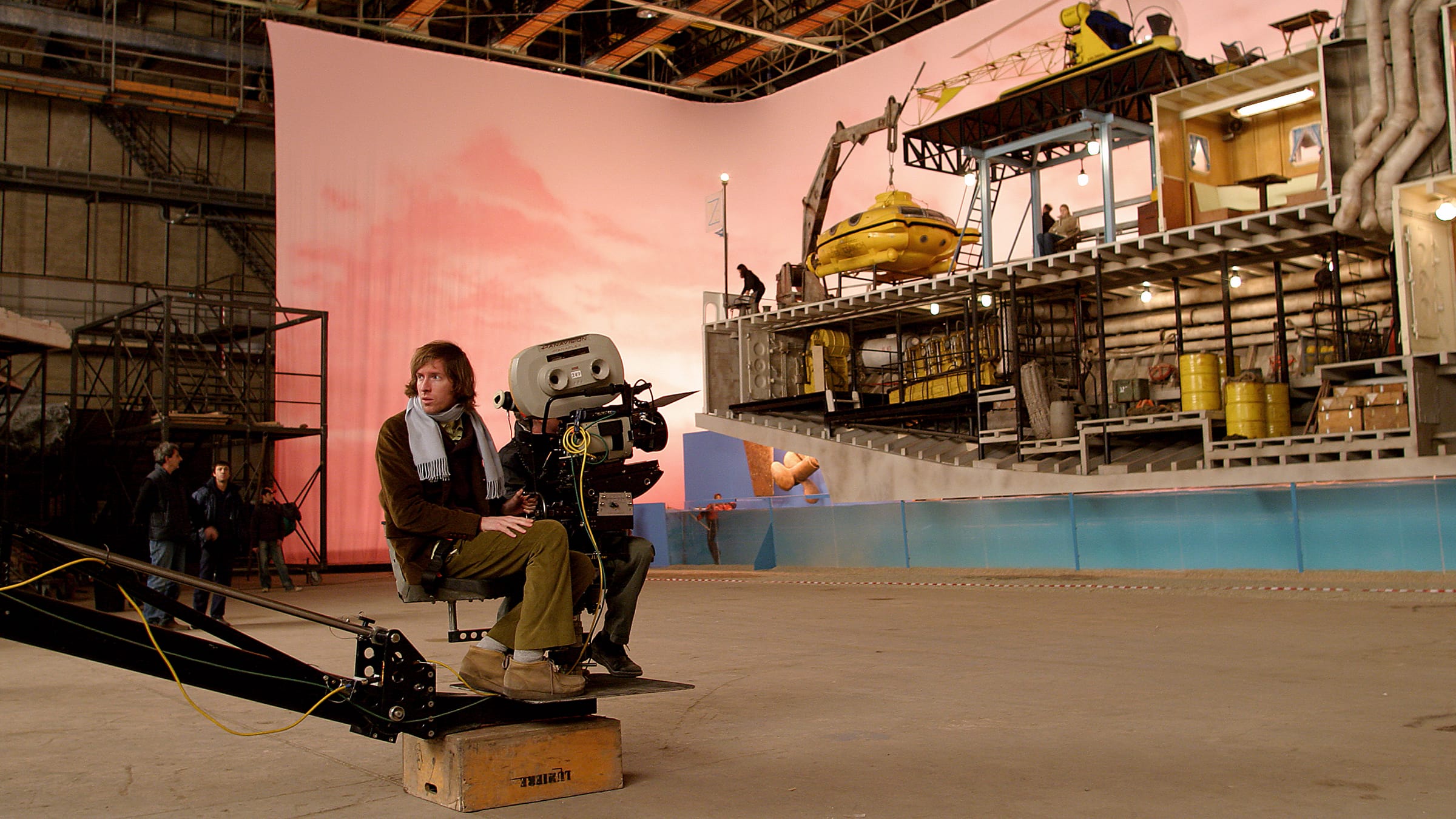

Bottle Rocket (an expansion of an earlier short) might be Anderson’s first masterpiece, but it didn’t entirely prepare us for what was to come. In subsequent years, Anderson’s work became still more childlike in stylistic spirit, even as the director developed a penchant for formal control perhaps unparalleled in modern American cinema. The languorous, alt-Texas mood of Bottle Rocket—released in the heyday of the 1990s indie revolution, a roughly defined movement that also introduced viewers to names like Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Kevin Smith, and Richard Linklater—soon gave way to the dry comedy and visual precision of Rushmore (1998), followed by the curated melancholy of The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004). And beyond—with each new effort somehow more wesandersonian than the previous one.

Is that in the dictionary yet, wesandersonian? It should be, if only because the other words so often used to describe the director’s films are all so insufficient: whimsical, quirky, twee. None of these terms really fit, because they seek to categorize, and thus reduce, something defined by its very uncategorizability (a word that also does not appear to be in the dictionary). The constant dance of regression and anticipation in his work spins around something inexact and inexplicable. His characters organize; they construct; they plan; they have rules; they have rituals. And it’s all in an effort to contain and understand an uncontainable, unknowable world.