Compensation: Archiving the Spirit

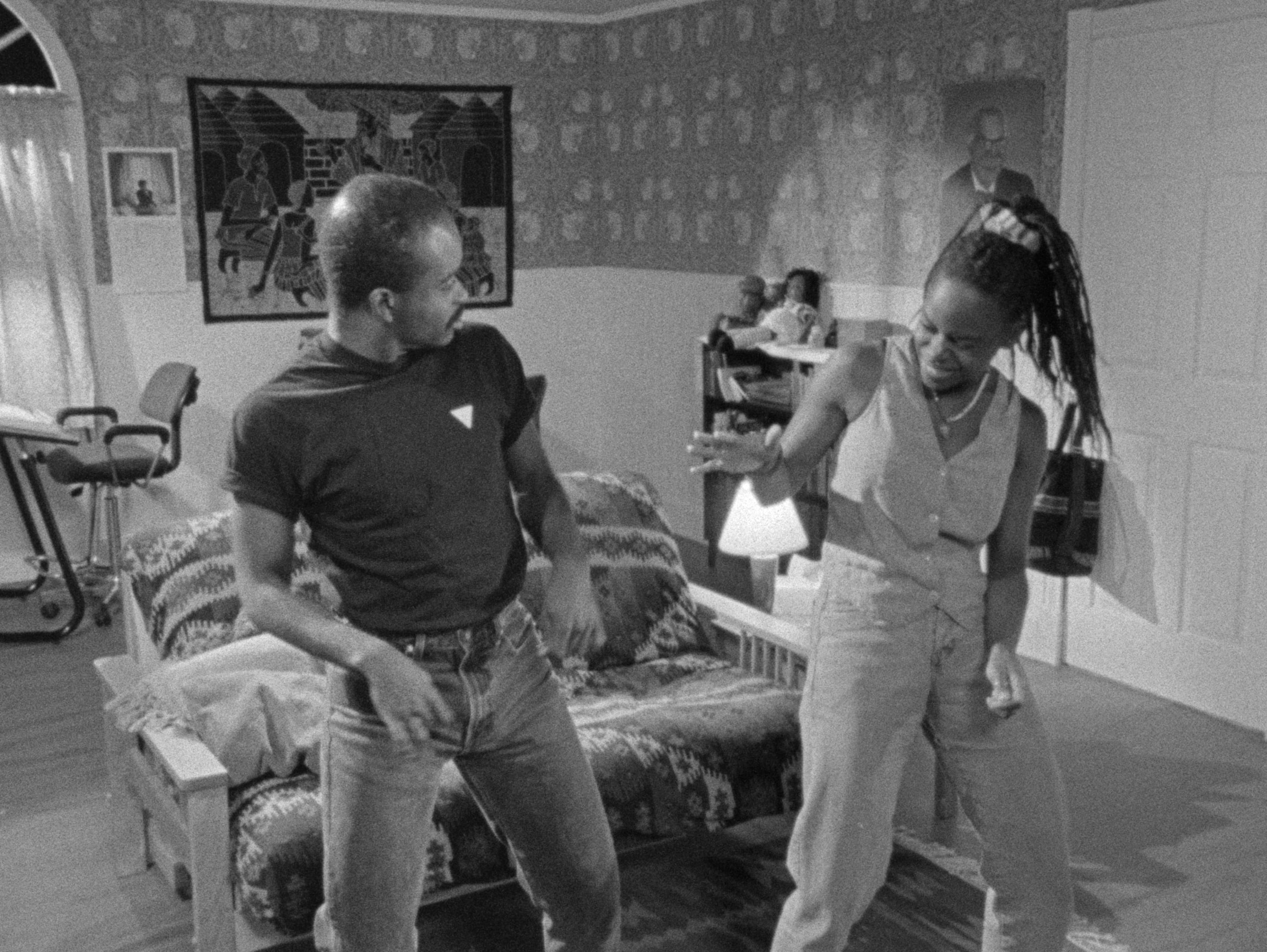

Early in Zeinabu irene Davis’s Compensation (1999), there is a scene where two of the main characters, Malindy and Arthur, attend a screening of the silent short The Railroad Porter. The pair and their friends react to the film in a way that is immediately recognizable to anyone who has grown up watching movies with Black audiences. The group laughs, utters shocked reactions, and talks back to the screen. “Oh, she got a gun too!” is a line that never fails to elicit laughter from me no matter how many times I watch Compensation. And it has been a source of joy to hear my own students react similarly to this scene, genuinely surprised that Davis has managed to capture something so familiar, so true, despite the 1910s setting. The distance between ourselves as movie watchers and the characters watching The Railroad Porter disappears, and we become a community, united through this shared experience. What Davis does here, and throughout Compensation, is go beyond creating scenes to articulate a sentiment, a feeling, that transports viewers into the lives and worlds of her characters.

The crown jewel in Davis’s multifaceted four-decade career as an independent filmmaker, and her sole narrative feature, Compensation captures the innovative spirit that characterizes her artistic identity. The film chronicles two parallel stories in very different time periods and social settings. Malindy is a Deaf seamstress living in Chicago in the early 1900s who experiences love and then loss when she connects with a hearing man, Arthur, who has recently arrived from the South. The second story—set in the 1990s, also in Chicago—focuses on Malaika, a Deaf artist who finds love with Nico, a hearing librarian, despite the difficulties that their relationship presents. Michelle A. Banks and John Earl Jelks play both couples. In addition to the unifying thread of the actors, a theme of pandemics connects the two story lines: in the first, Arthur is beset by tuberculosis, and in the second, we learn that Malaika is HIV-positive. In interweaving these two historically specific scenarios, Davis shows that love, hope, and resilience can offer a balm amid times of crisis.

Compensation’s brilliance lies not only in its compelling storytelling but also in its ability to make porous the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction, between past and present. For instance, the film opens with archival photographs and uses them throughout the narrative, in a way that creates a simultaneous sense of both historicity and timelessness. This is just one of the formal techniques that Davis deftly employs to help immerse the viewer in the worlds that she has created; others include frequent intertitles and open captioning.