Rome, June 1945. The magazine Film d’oggi (Today’s Films) runs an article by Vittorio De Sica about the boys who work shining shoes in the city, saying he wants to make a film about them. Accompanying the article are sixteen photographs by Piero Portalupi that capture the staring faces and ragged clothes of some of the shoeshine boys. One shows a boy named Giuseppe in the Villa Borghese park riding a horse he has rented with his earnings.

Elsewhere in the city, Roberto Rossellini has just finished directing Rome Open City. Now in postproduction, it will premiere in September. The film reconstructs the resistance to the Nazi occupation of Rome, which had ended a year earlier, while De Sica’s Shoeshine, which he starts shooting that October (his seventh film as director), centers on the social conditions after the city was liberated, particularly as they affected children. Stories of wartime resistance and stories of postwar social conditions are the two faces of what critics will come to label “neorealism” in Italian cinema.

Across Europe, World War II left a legacy of inflated prices, hunger and malnutrition, disease and impairment, poverty and homelessness, along with thousands of orphans and displaced children. Shoeshine, released in April 1946, was the first postwar feature film to deal critically with these young people’s plight. We will see it again soon afterward in Rossellini’s Paisan, released in December the same year, where a young orphan steals to survive and lives with other homeless people in a cave in Naples, as well as in the same director’s Germany Year Zero (1948), centered on a twelve-year-old boy in a devastated postwar Berlin.

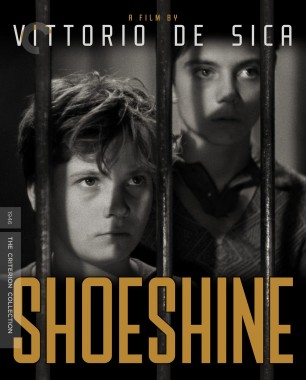

The story outline of Shoeshine, written by Cesare Zavattini, tells of two shoeshine boys who dream of buying their own horse. In the film, they are played by fourteen-year-old Franco Interlenghi (Pasquale) and twelve-year-old Rinaldo Smordoni (Giuseppe). Needing extra money for the purchase, they become unwitting accessories to a theft. They are picked up by the police and sent to a juvenile prison pending trial. The arrest happens, in the film, after just fifteen minutes, and most of the rest of the action, over an hour, takes place in the prison before and after their sentencing in the courtroom.

In fact, despite its title, what the film is principally about, in a social sense, is not the life of the shoeshine boys nor child labor—there are just two short scenes where shoes get shined—but incarceration and the various forms of violence and petty cruelty, psychological as well as physical, that are inflicted on the young prisoners, both by adults and by the boys themselves on each other. One boy is berated as “stupid” by Staffera (Emilio Cigoli), the prison governor’s assistant, when he makes an error in a multiplication table. When Giuseppe first arrives in his cell, the other boys tease him, saying that since the prison authorities took prints of four fingers, he will be inside for four years, and when Giuseppe then bursts into tears, they laugh at him.

The film also shows the standard routines and modes of discipline of what sociologist Erving Goffman called “total institutions”—prisons, concentration camps, military barracks, “insane asylums”—but it is not about those institutions in general. It is specifically about a prison for boys and the norms of behavior expected in the 1940s of young Italian males, internalized and regulated by the boys themselves. In that society, a boy was not supposed to show any weakness, and his most unforgivable transgression would have been to rat on someone else. In fact, the film’s working title was Ragazzi (Boys). That word remains in the opening titles, where it appears in parentheses just below the film’s title, against a shot of the large interior hall of the prison in Rome.

The prison depicted was a real one. It was part of a large complex called San Michele a Ripa Grande, in the Trastevere neighborhood. Originally an orphanage, since the late nineteenth century part of it had been used as a “reformatory” for offenders under twenty-one. There is a shot of the actual entrance to the building when Pasquale and Giuseppe arrive in the police van, but the large hall, the cells, and the other rooms were, like all of the film’s interiors, built in the studios of the film’s production company, Scalera. The actual design of the large hall, with its distinctive two tiers of arches over the cell doors, was adapted by production designer Ivo Battelli to create a theatrical space. Shadows of window bars, absent in the real building, are cast at oblique angles across the floor and walls. Another addition was the spiral staircase that winds up the back wall to a small door through which prison officers enter and exit.

The relatively faithful reconstruction of a real place and the theatricalization of that space, enhanced by the lighting of cinematographer Anchise Brizzi, mirror the duality of the film as a whole. On the one hand, Shoeshine has a documentary realism of places and faces. The two principal boys had no previous acting experience and were cast on the basis of their physical appearance, their faces in particular, consistent with the photo-story that was the original nucleus of the film. Their remarkably sensitive performances owe much to De Sica’s skill as an experienced film actor (he had had a successful acting career before he started making his own films) in directing untrained ones, modeling gestures, movements, and expressions. On the other hand, many of the interior shots in the prison are framed and lit in a way that exaggerates, in a quasi-expressionist style, the atmosphere of confinement, with shadows of the cell bars projected onto the boys’ faces and sometimes obscuring their eyes.

A contrast between light and dark also bookends the film as a whole. It begins in bright daylight in the open space of Villa Borghese, where the boys ride their horse, Bersagliere, and it ends with a studio-shot nighttime scene in which the same horse, their shared object of desire for escape, stands out, with its light-toned body, against a dark background. In between, there are the dark interiors of the prison, a space of coercion and violence.

The film is remarkable for the way it stays centered on the children’s perspective on people and events and doesn’t stray from that into an adult moral framing. De Sica’s earlier film The Children Are Watching Us (1944) had also adopted a child’s view: a five-year-old boy sees his mother’s assignations with her lover and then witnesses the breakup of his parents’ marriage. In Shoeshine, similarly, we apprehend the adult world with Pasquale and Giuseppe, and even when they are not in shot, we receive their impressions of its indifference or hostility. Nearly all the adults are hard and uncaring, mere vehicles of their institutional roles, like Staffera and the prison governor (Mario Volpicelli), or greedy and selfish, like the fence Panza (Gino Saltamerenda) and his accomplice, Giuseppe’s older brother Attilio (Guido Gentili), who set the two young boys up as stooges for the theft and then make them swear they saw nothing to protect themselves from arrest. The few exceptions, like the kind liaison officer Bartoli (Antonio Nicotra), are too weak to challenge authority. He pleads with the boys to stay out of trouble and play by the rules, and in that way he, too, colludes with the system.

Some shots in Shoeshine have been fixed in my memory ever since I first saw it. One is the agonized expression of Pasquale when he believes he hears Giuseppe being beaten with a strap in an adjoining room. We are shown what Pasquale does not see—that the beating of his friend is faked, that another child is pretending to take the blows while Giuseppe has been taken out of the room—but that does not make Pasquale’s suffering any less real. Another indelible image is that of Pasquale’s face, again, this time full of terror, as Staffera removes his belt to beat him in his cell for something he did not do. The powerful effect of these scenes on me, I realize, is partly to do with memories of my own childhood that they trigger. I grew up in a much more comfortable home environment than the shoeshine boys in the film, but in the all-boys junior school that I attended in London in the late fifties and early sixties, corporal punishment was standard practice. I still remember the pain and humiliation of being caned—usually for “bad conduct”—and how I would hide afterward in the school toilets while my tears dried so my classmates would see me return defiant and not as “a baby.” It is very likely that De Sica as well as the writers who worked on the screenplay—Sergio Amidei, Adolfo Franci, Cesare Giulio Viola, and Zavattini—all had some experience of similar beatings as children.

Those depictions of institutional violence and coercion, and of adult cruelty and indifference, are central to the film. There is also an implied political critique of the policing and carceral systems as continuations of the defeated Fascist regime, notably in the sequence with the prison governor, written by the Communist Amidei, who also wrote the part of the resistance leader Manfredi in Rome Open City. But for me, Shoeshine is also something more. It is a story about a friendship. It is about the unbreakable bond between two adolescent boys. Their friendship is a stronger tie than that of family. Giuseppe is content to leave his own family (who in any case are sharing overcrowded temporary housing with two other families displaced after bombing raids) and to sleep in the stable next to Pasquale, his orphaned friend, and near their horse. So strong is their friendship that it survives their separation in prison. Giuseppe refuses to let go of Pasquale’s hands when the latter is put in a separate cell, and they are later overjoyed when they are able to see each other again. Their bond survives even their mutual suspicions of betrayal and their jealousy at being supplanted. Giuseppe is taken under the wing of the manipulative Arcangeli (Bruno Ortenzi), and Pasquale looks after the sickly Raffaele (Aniello Mele). Both boys therefore reproduce with another their relationship with each other, but only in form: Giuseppe gets a new taller and older protector in Arcangeli, but the latter is purely self-interested. Pasquale becomes the protector of the younger Raffaele, but it is a temporary nurturing role, not a durable friendship.

The friendship between Pasquale and Giuseppe evokes other famous male friendships in the literary tradition that end with the death of one and the grief of the other. When Achilles laments Patroclus in The Iliad, he refuses all food, decides to join the battle, kills Hector, and drags his body behind his chariot to avenge his dead friend. In Montaigne’s essay on friendship, about Étienne de La Boétie, he says that their kind of friendship was superior to heterosexual love, since that rises and falls with the flames of passion whereas theirs was more constant and lasting. Shoeshine inherits this homosocial tradition—defined by an intense and quasi-erotic male bond—together with some of the misogyny that often goes along with it. The female characters are either passive spectators, like little Nannarella (Anna Pedoni), Giuseppe’s neighbor, who sees him off as he is taken away in the police van, and who cries in the courtroom when he receives his sentence, or go-betweens for someone else, like the woman who comes to the prison to tell, stiffly, the tearful Raffaele that his mother is out of town and cannot see him.

So Shoeshine is about boys and the codes and conventions of masculine behavior, and yet the friendship it depicts has an intense warmth that transcends those codes. But the jealousy and rage that same friendship generates lead to its tragic ending. Giuseppe escapes from the prison with Pasquale’s hated rival, Arcangeli, and they take Bersagliere, Pasquale and Giuseppe’s horse. Pasquale, enraged, tells the prison staff that he knows where the two fugitives are, so they take him with them in pursuit. Pasquale intercepts Giuseppe and Arcangeli as they cross a bridge on the horse. He wields a pointed iron bar that scares off Arcangeli, then removes his belt to punish Giuseppe, who backs away and falls through a broken parapet onto the rocks below. The shot of Pasquale beating Giuseppe with his belt has a bitter irony, recalling that earlier scene in which Pasquale, his eyes wet with tears, pleaded with the prison officer to stop the beating of his friend.

The film concludes with the most painful shot of all: Pasquale on the riverbed cradling Giuseppe, whose death he has accidentally caused. After repeatedly shaking Giuseppe and finding him unresponsive, Pasquale lays his head on his shoulder and cries out “C’ho fatto?” (“What have I done?”). It’s an immensely moving and tender scene, not least because it recalls other shots, early in the film, in which the two boys are also physically close: sitting together astride Bersagliere, their chins raised proudly as they mimic policemen or soldiers and the other street children cheer them, or waking up in a stable beside each other, and their horse, as sunlight streams in. The image of Pasquale grieving is such a private moment that the film respectfully cuts away to the pained face of Staffera, who has just arrived, and then follows his gaze as he turns to the sound of Bersagliere neighing. We then see the horse amble away as the end title appears.

It’s an ending that resists facile dramatic closure because it offers the audience no relief from the grief of the orphan Pasquale, now truly alone. In this, it is like some other neorealist films involving children. The boys in the final shot of Rome Open City walk away after witnessing the execution of their beloved priest. Edmund (Edmund Meschke), at the end of Germany Year Zero, throws himself from a high floor of a derelict building after having poisoned his father in an ill-conceived mercy killing. Even when Bruno (Enzo Staiola), at the end of De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), takes his father’s hand after he has been caught trying to steal a bicycle, he knows that his father remains unemployed and desperate and that the future is uncertain. As in the real world, in this stark film world there are no easy consolations.

More: Essays

Birth: Love Eternal

Jonathan Glazer’s enigmatic second feature explores the terrors of being desperate for love—and the vulnerability, loneliness, and difficulty in understanding other people that might drive this state.

Kiss of the Spider Woman: Revolutionary Transgressions

A resounding critical and popular success upon its release, Héctor Babenco’s adaptation of a literary masterpiece by Manuel Puig was an unprecedented cinematic fusion of a radical politics of sex with a sexual politics of revolution.

House Party: What’s Understood

Unencumbered by the white gaze, Reginald Hudlin’s groundbreaking feature-film debut is a celebration of a Black community in all its diversity, featuring fully realized characters who exist not as spectacle but as reality.

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project No. 5

Yam daabo: On Idrissa Ouédraogo’s Humanist Cinema

A deft mixture of family epic, romantic melodrama, landscape cinema, and comedy, Burkinabe director Idrissa Ouédraogo’s landmark film balances the universality of its themes with the fierce individuality of its characters.