A Confucian Confusion and Mahjong: State of Transaction

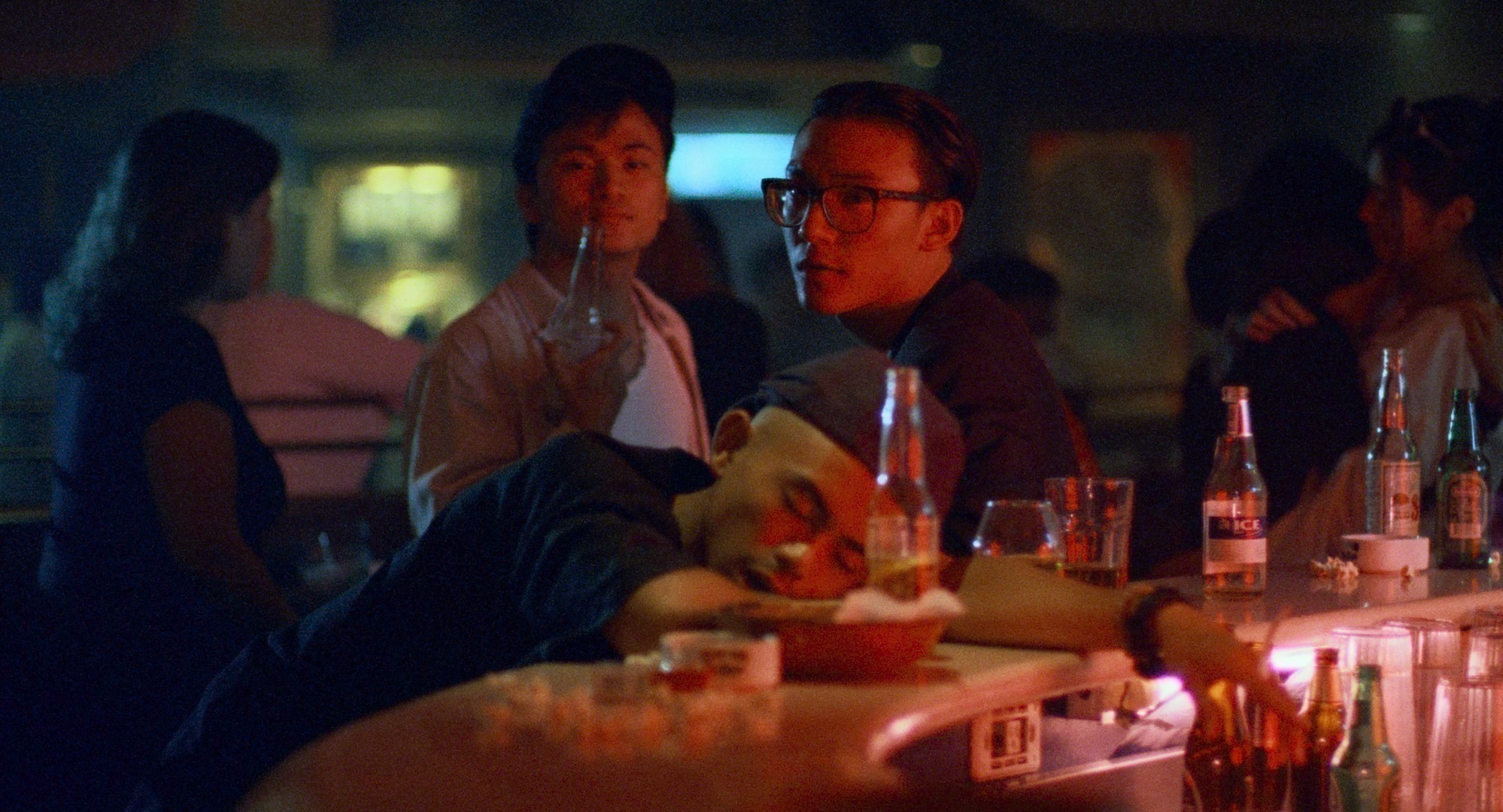

Some filmmakers have a skill for bringing the past to life, others for imagining the future. Edward Yang was a master of seeing the present. It can be hard to make out the shape of things as they form before us, but with his analytical mind, his intuitive grasp of social context, and his unerring sensitivity to the workings of inner life, the great Taiwanese director seemed to understand in real time how world-historical shifts were rewiring the human psyche, before most others had even found the vocabulary to describe what was happening. Yang died in 2007, at the too-young age of fifty-nine, and the loss still feels profound, not least because a moment like ours—muddled, cluttered, prone to mendacity and obfuscation—could so badly use his cutting lucidity. An artist for complex times if ever there was one, he was capable of diagnosing their ills and appreciating their absurdities, and this was never more evident than in his fifth and sixth features, A Confucian Confusion (1994) and Mahjong (1996).

How should we think of the 1990s? The decade that followed the so-called end of history also marked the centenary of cinema and sowed many of the seeds of our present dysfunction. Taiwan provided a front-row seat to one of the period’s most distinctive features: the seductive and pernicious spread of global capital. The island nation was at the time navigating a transition from authoritarian rule—1987 marked the end of almost four decades of martial law—to neoliberal democracy. Yang recognized that the attendant influx of money was transforming everything from Taiwan’s position in the world, not least its tricky triangulation with China and the United States, to its people’s core values and identity. Born in Shanghai, raised in Taipei, and naturalized as an American citizen after spending much of his adulthood in the U.S., where he studied and worked in computer systems, Yang brought an effortless cross-cultural literacy, along with a healthy skepticism, to his dispatches from a fast-changing, increasingly cosmopolitan Taiwan. He once claimed that the country’s decades of political repression were not necessarily worse than its boom years, observing that “one can hide a lot of things under democracy.” With A Confucian Confusion and Mahjong—both of which are attuned to the visible and the intangible manifestations of the nominally free, relentlessly free-market nineties—Yang sought to uncover what was hidden, often in plain sight, looking past the shiny Taipei skyline to the fault lines beneath the surface.

If these two films have been somewhat neglected in assessments of Yang’s oeuvre, it is in part because they are chronologically bookended by A Brighter Summer Day (1991) and Yi Yi (2000). The former is a richly detailed, autobiographically inflected epic of adolescence, expansive in its historical sweep and redolent with sense memories; the latter, which turned out to be Yang’s swan song, is a multigenerational drama that seems to contain all of human feeling, a magisterial work of hard-won wisdom and deeply moving equipoise. The two movies that he made between these magnum opuses evince many of the opposite qualities. Instead of gravity and scope, they aim for fleetness and compression. Both are briskly plotted and densely populated ensemble pieces, unfolding over a few eventful days and nights. They are also often typified—and sometimes dismissed—as comedies, although that simple descriptor understates the ease with which they combine tones and switch registers, deploying genre stylization and sardonic wit in the service of ideas that come thick and fast.

Befitting its title, A Confucian Confusion introduces, in rapid succession, more characters than we can easily track. Their relationships are initially unclear, though we soon realize that these dynamics are always fluctuating, as one person’s value relative to another rises or dips like a stock-market ticker. Unafraid of big themes, Yang gravitated to the clash of large forces, to eternal binaries that could illuminate particular conditions of existence: the push-pull of tradition and modernity in Taipei Story (1985); the vertiginous blurring of fiction and life in The Terrorizers (1986). In A Confucian Confusion, whose characters smudge personal and professional distinctions into oblivion, he trains his sights on the queasy bedfellows of art and commerce.

The hub of the action is a Taipei creative agency, run by the coolly imperious Molly (Joyce Ni) and bankrolled by her feckless man-child fiancé, Akeem (Wang Bosen). While Molly engages in a perpetual backroom game of manipulation and rumormongering, the business of running the firm—which churns out pablum like commercials, soap operas, and a bromide-choked talk show hosted by Molly’s sister (Chen Li-mei)—falls to her loyal lieutenant, Qiqi (Chen Shiang-chyi), whose boyfriend, a government bureaucrat named Ming (Wang Wei-ming), resents Molly’s outsize presence in their lives. The intrigue escalates when Molly abruptly decides to terminate one of her employees, Feng (Richie Li)—or, rather, orders Qiqi to do it—because she senses (correctly) that the new hire, an aspiring actress, is sleeping with Akeem’s slippery henchman, Larry (Danny Deng).

Orbiting this carousel of characters are two artists, both negotiating career crossroads. Playwright Birdy (Wang Ye-ming)—introduced in the opening scene on Rollerblades, skating literal circles around a roomful of journalists—announces a newfound belief in populism: in a flattened utopia where “everyone thinks alike,” an artist should serve the democracy of the box office (“buying a ticket is like voting”). Birdy is defending a plagiarism charge, having purportedly lifted ideas from a novelist (Hung Hung) who is also the estranged husband of Molly’s sister. The novelist’s trajectory is the opposite of the playwright’s: once a best-selling romance author, idolized by teenage girls, he has turned to spartan seclusion and glum philosophizing, and is hawking an unpublishable manuscript about the reincarnation of Confucius, who arrives in the present day to find himself celebrated as a con artist par excellence (no prizes for guessing what it’s called).