Jonathan pursues a model named Bobbie (Ann-Margret, in an Oscar-nominated performance that suggests a fall from innocence since her star-making role as the teenage heroine in 1963’s Bye Bye Birdie), and he takes pleasure in pawing her and parading her around like a trophy. But once he has convinced her to move in with him, and to stop working, he becomes enraged by her boredom and depression. In one scene, he tells Sandy to rape her: “She won’t even notice.”

In the abbreviated final act, we learn that Jonathan and Sandy have split from their partners. It is now the seventies, and both men are forty. Sandy is seeing a long-haired and vacant-eyed eighteen-year-old named Jennifer (Carol Kane), whom he brings to Jonathan’s apartment to watch a slideshow of “ballbusters” that Jonathan has made, featuring pictures of all the women he has loved and, therefore, hated. Susan flashes across the screen for an instant, before Jonathan hurriedly clicks to the next image; we see Sandy’s face, but it is not clear if he has taken notice of the photograph, which reveals the film’s central secret. After Jennifer leaves, annoyed, the two men walk the dark streets of New York, talking while looking down, hands jammed into their pockets.

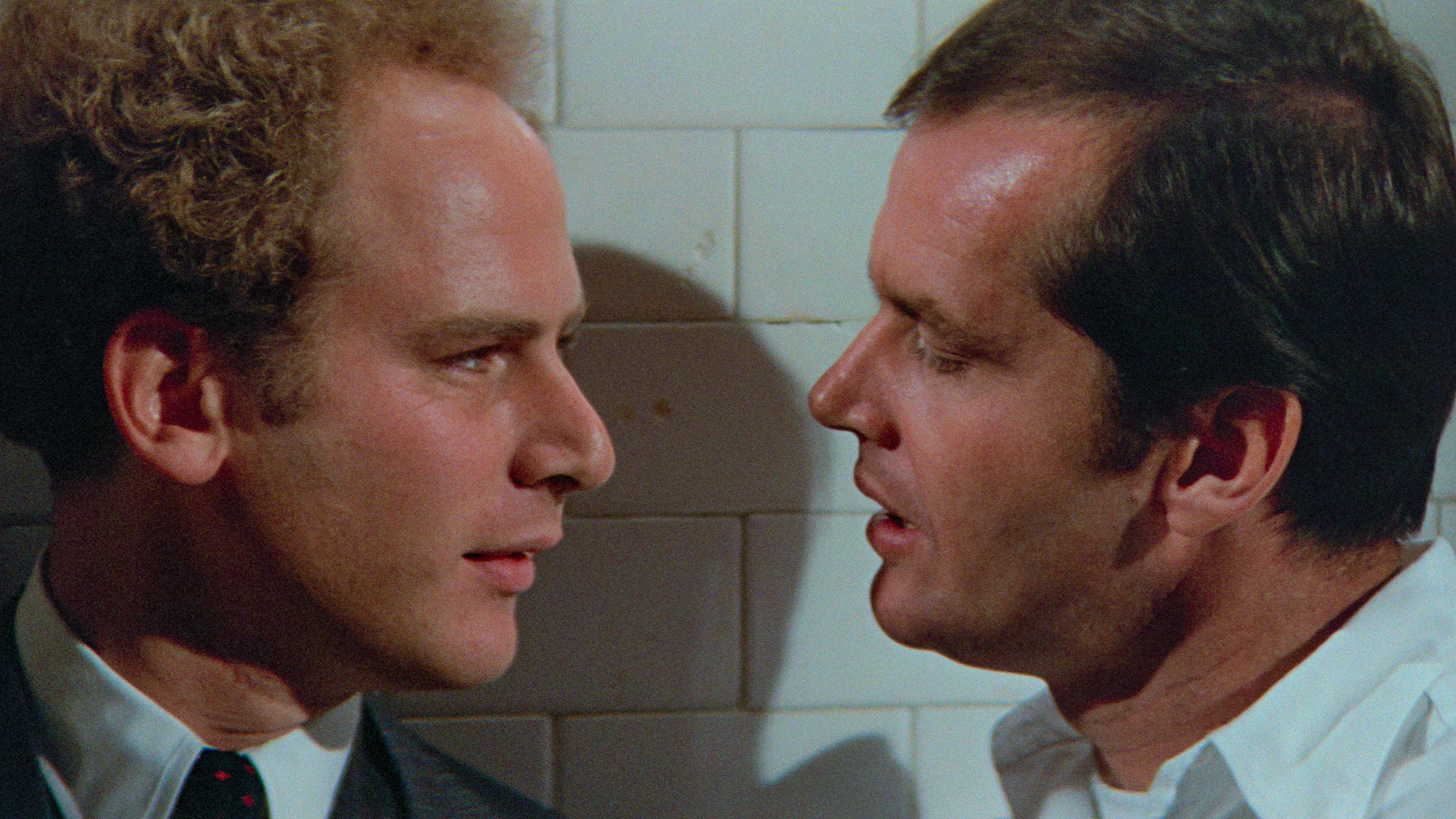

Carnal Knowledge is incredibly precise, at the level of both narrative and mise-en-scène. Throughout, Nichols uses two stylistic signatures to enact the alienation that his characters experience, as they try to navigate a world where love and lust are supposed to be newly free and yet old customs persist. Monologues shot in close-up are one such motif. Again and again, Jonathan and Sandy speak directly to the camera. The stylized stasis of these images and the characters’ stagy, slightly stilted language belie the apparent forthrightness of their address. The effect is of an alienated intimacy, from oneself and others. If these scenes let us eavesdrop on the way that these men speak to themselves, they also serve as performances of the people they imagine themselves to be.

Prevalent, too, is the sound of two male voices in dialogue, as heard in the opening moments. Even with the friends’ sexual bravado, the acoustics in their dorm room and the tentative way they sound each other out generate more tenderness than either man is capable of giving in his relationships with women. In the push-pull dynamic of the men’s self-reflections, we discover the film’s true subject: the mix of love, narcissism, and resentment that underlies their friendship, and which is echoed in their last exchange. Having left Susan and his children in the suburbs, Sandy says that his new girlfriend is helping him to finally learn who he is. “Sandy, I love you,” Jonathan responds, “but you’re a schmuck.”

The two stunning central performances heighten the film’s effect. Nicholson is kinetic; often dry, with rolling eyes and a perked brow; but tense like a coil. As in Five Easy Pieces (1970) and The Shining (1980), it feels like he could do anything at any moment. When Jonathan learns that Bobbie has tried to kill herself, he rends the screen with screaming rage. By comparison, Garfunkel is quiet and slow. He seems a little dim. And yet his delays perfectly fit his character, who is always trying to do the right thing—or thinks he is. Sandy’s first conversation with Susan is about whether people are always acting; when he later insists to Jonathan that he and Susan “do all the right things,” he seems to be trying to talk himself out of his evident unhappiness. By the end, even after he has left his family and gotten together with Jennifer, he clearly still thinks he is performing the right role.

Jonathan, who had flirted years ago with Susan by calling out the “codes” that other men and women use in courtship, calls Sandy on his bullshit. The question of whether Sandy realizes his friend once betrayed him with his now-ex-wife has been briefly raised but never really addressed. It seems most likely that Sandy doesn’t know. In the absence of a confrontation, “I love you, but you’re a schmuck” feels like the truest thing—the closest thing to knowledge—that passes between the two men.

To depict something is not necessarily to endorse it. There is no way to read Carnal Knowledge as celebrating the behavior of its main characters. Even before the absurd last scene, in which Jonathan makes a routine visit to a sex worker (Rita Moreno) whom he pays a hundred dollars to talk him into an erection (“You’re always right, lover”), we know these men are pathetic. Nichols and screenwriter Jules Feiffer knew that too. Feiffer described his original playscript, which he had sent to Nichols and upon which the film is based, as a story about how “heterosexual men don’t like women.” Nichols biographer Mark Harris has noted that the director saw the play as a warning about what he could easily become in middle age.

Despite the self-awareness of its creators, Carnal Knowledge angered critics when it was released. John Simon complained of the film’s “unconscious vindictiveness” and “unbreathable monomania.” The director and acting teacher Kristin Linklater wrote in a letter to the New York Times that, if she had had one handy, she would have thrown a bomb into the projection booth. The New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael complained—as she later would about Nichols’s Heartburn (1986), which stars Nicholson as another cad and Meryl Streep as a version of writer Nora Ephron—that Carnal Knowledge was too black-and-white. She disliked how the movie seemed to condemn the behavior of its leading men and “never let them win a round”; she called it “show business fundamentalism.” Yet, for all this negative press, Carnal Knowledge became a cultural touchstone. In an irony that we are now all used to, in our age of anti-fans and hate-watching, the outrage became a key driver of the movie’s success.