Because I loved This Is Our Youth so much, I admit that I was a little nervous about seeing You Can Count on Me. It is rare for a playwright to have the opportunity to make their own film, especially as a first-time writer-director. (It wasn’t common knowledge then that Lonergan was already a professional screenwriter. He’d been able to support himself while writing This Is Our Youth by selling the original screenplay that would eventually be produced as Harold Ramis’s Analyze This.) I knew from my own experience that transitioning from writing for the stage to writing for the screen could be surprisingly difficult.

I was nervous because I’d always had it impressed on me that screenplays have to follow a strict formula. Movie audiences, I’d been taught, are trained to expect certain events to happen at a certain pace. This pace demands a lot of action and an understanding that film is a visual medium. Theater is . . . well, a visual medium, too, obviously, but one that maybe relies less on convention than commercial film does. A play usually allows an audience time to enter its world and reflect on its ideas and characters, just as a novel does. In fact, a play is sometimes described as a cross between a novel and a film. Theater is immediate and visceral, like film, but also contemplative, like prose. Lonergan had realized these qualities perfectly in This Is Our Youth, but I wasn’t sure if they would translate to film.

Of course, I needn’t have worried. Less than a minute into the movie, watching the scene in which the sheriff rings the Prescotts’ doorbell to deliver the news of the parents’ accident, I knew that Lonergan had captured the best parts of both playwriting and filmmaking. His visual storytelling, beautifully realized by cinematographer Stephen Kazmierski, is expert. As opposed to the gradual way that world-building and exposition unfold onstage, it takes Lonergan mere seconds to establish time, place, tone, character, and mood on-screen. His cinematic language is deft and economical, but it doesn’t leave the audience passive. Played with consummate delicacy, the scene between Amy, the babysitter (Halley Feiffer), and Darryl, the sheriff (Adam LeFevre), instead invites us in to experience and ponder what is happening in an active way, just as theater does at its best.

The sequence begins with an establishing shot of the Prescotts’ tidy New England farmhouse, its porch light spilling into the darkness, its white picket fence exuding order and respectability. We hear the reassuring whir of crickets. Next, looking out from inside the house through frosted glass framed by white, scalloped curtains, we see the blur of a dark figure approaching. An old cartoon is blaring on a TV somewhere. On the cartoon’s soundtrack a doorbell rings, followed by a cackle. Then the Prescotts’ actual doorbell rings, and the figure on the front porch draws nearer. The shape suggests a man in a dark uniform and hat. The badge on his chest seems to shimmer—as does the entire scene—with both warmth and menace.

When Amy opens the door to Darryl, we see young Sammy and Terry lying on the floor of the living room behind her. They are the ones watching TV, innocently oblivious to what is about to take place. Amy is a girl herself, still in braces, but she’s old enough to know to be wary. Sheriffs never arrive on a doorstep with good news. Darryl tries to reassure her with a weak smile. They call each other by name because this is a small town where everyone knows each other. When Darryl asks Amy to step outside and close the door, her wariness turns to distress. She might even cry. She waits to hear whatever terrible news Darryl has to deliver, but he only stands there. How does he put the horrific into words? He opens his mouth to speak and . . . the scene ends.

When that scene ended without a speech or a heart-to-heart with the kids, I knew that Lonergan’s strengths as a playwright would only be enriched in this new medium. All the audience needs, at that point, is to see the expression on Darryl’s face. That brief but lingering close-up provides us with a sort of ellipsis that allows us to absorb his helplessness and grief. If the same scene were played onstage, where there are no close-ups, the audience might have felt robbed. A playwright might have felt compelled to fill in the ellipsis with words. But when Lonergan left Darryl silent, cutting from his expression to the title sequence, I knew he had embraced the exciting, freeing elements of filmmaking without sacrificing any of the depth of his work for the theater.

This blend of narrative economy and deep, often conflicting, emotion characterizes the entire picture. At the Prescotts’ funeral, for instance, the minister delivers her eulogy directly to Sammy and Terry, but all we hear are the haunting strains of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. There is no diegetic sound. The minister seems to want desperately to help the two children, but because we can only see her lips moving (another ellipsis), we understand that nothing she says can ever be enough.

As the minister speaks, Sammy and Terry sit in the pew staring straight ahead at their parents’ caskets. Next to them sits an older woman, rigid and apart. We assume that she’s an aunt. She doesn’t look at Sammy and Terry, or reach out to them. Perhaps she’s emotionally distant, or perhaps she doesn’t know how to respond to the huge responsibility that has been thrust upon her, of raising two children. We never find out, but whatever the reason, we fear that she won’t be able to give the kids the love they need. Our fear is realized when the camera pulls back and we see that Sammy and Terry are clutching each other’s hands. These two know already that from now on, they’ve got only each other.

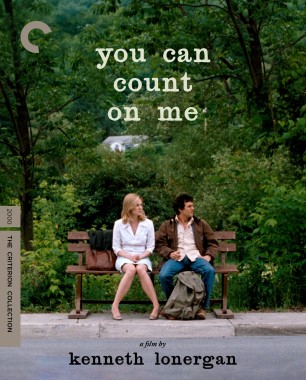

That image of the two children clinging together informs the rest of the film. We leap ahead to find Sammy and Terry as adults. We don’t know what exactly has happened in the intervening sixteen years, but we soon find out that their lives have diverged in significant, possibly irreparable, ways. They’ve grown up, but through the subtle, pitch-perfect performances of Laura Linney as Sammy and Mark Ruffalo as Terry, we never lose sight of their early trauma. Not that they wallow in it. There is no sentimentality in this film. Neither of them invokes that trauma to explain or excuse their mistakes, but we know it’s there.