These visual flourishes were, in part, a way of suggesting violence that could not be explicitly shown. Most famously, Hawks incorporated Xs into scenes where people are killed—a motif first established by Tony’s crisscross facial scar—offering the crew rewards of fifty and then one hundred dollars for thinking up ways to work them in. They are traced by shadows and streaks of light, painted on signs, formed by girders in a warehouse or the blades of a desk fan, marked on a bowling score sheet, and attached to a door in what must be the only apartment building in Chicago to identify rooms with Roman numerals. Aside from offering viewers an entertaining challenge in finding them, the Xs insouciantly advertise the film’s aestheticization of death. Who can mourn the loss of human life when they are busy admiring the artfulness of a bird’s-eye shot in which the shadow of an undertaker’s sign splashes a cross over a body sprawled on the pavement?

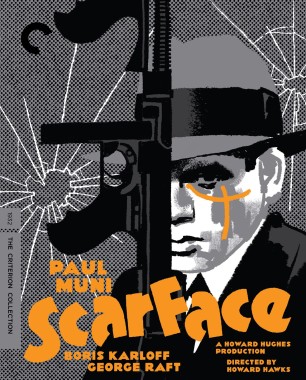

The established studios resented Hughes as an upstart and were loath to loan out their stars for his productions, one reason why most of the Scarface cast were relative newcomers. Paul Muni had returned to Broadway after making two unsuccessful films in 1929. A serious and cerebral actor who had honed his craft in the Yiddish theater, Muni initially felt he was wrong for the role of Tony Camonte, but once persuaded he dove in with his customary gusto, and during filming Hawks worked to tone down his flamboyance and the unintelligibly thick accent he had adopted. Italian American groups protested the heavy-browed, simian caricature he drew, but his performance is supercharged with animal spirits and refined by the imagination he brings to small details: the way Tony watches and imitates Poppy plucking her eyebrows, or how pleased he is with his analysis of the W. Somerset Maugham–derived play Rain (“This girl, Sadie, she’s been whatta you call . . . disillusioned”). Tony is scheming to take over the beer business on the South Side of Chicago, stir up a gang war with the North Side, and displace his boss, Lovo, but in the moment he is genuinely, single-mindedly interested in which man Sadie Thompson will wind up with, in Poppy’s grooming technique, in the interior decor of his new digs. This quality is dangerously disarming.

Poppy is at first repelled by Tony’s vulgarity, but once she comes to his apartment she succumbs to his naive, unquenchable enthusiasm. Fingering his garish dressing gown, she slyly mimics his trademark phrases: “Dat’sa pwutty hot. ’Spensive, eh?” (Observing and copying each other is a standard Hawksian mating ritual.) Her amusement gives us permission to be charmed by Tony, who can also be terrifying in his psychotic rages—especially those aimed at his sister, Cesca (Ann Dvorak). Though Hawks later claimed he had come up with the idea of basing the Camontes on the Borgias—complete with an incestuous sibling attachment—Scarface dialogue writer John Lee Mahin insisted that credit belonged to Hecht, who had a long-standing love for the infamous family. That may well be, but the prominence of women in the movie—compared with their usually peripheral roles in gangster films—is typical of Hawks, who would raise Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s hard-boiled newspaper comedy The Front Page (first adapted to film by Howard Hughes in 1931) to new heights by switching the gender of reporter Hildy Johnson from male to female in His Girl Friday (1940).

Poppy is probably the smartest person in the movie, and possibly the most amoral. She is also the story’s only survivor. Cesca is something else entirely. Tony’s unnatural obsession with his sister is established as soon as she is introduced, when he berates her for kissing a young man; she recognizes and recoils from his unbrotherly attentions, but she also realizes, and eventually accepts, that she is just like him—that, in some sense, she is him.

Ann Dvorak was still in her late teens when she came to a party at Hawks’s house, and he was dazzled by the slim dancer and former child actor. He later recalled an incident during the evening in which George Raft, who had been cast as Tony’s right-hand man, Guino Rinaldo, initially rebuffed Dvorak’s invitation to dance; to change his mind, she performed an enticing slow shimmy in front of him. Hawks restaged this bit of business in the film, when Cesca undulates to the bluesy “Some of These Days” in an attempt to lure Guino onto the dance floor in a nightclub. (Alas, she is unsuccessful, and we don’t get to see Raft cut a rug in this film; a former professional dancer, he performs a sinuous soft-shoe in Rowland Brown’s 1931 gangster gem Quick Millions and beats Cagney in a foxtrot contest in 1932’s Taxi!) When she appears in the Paradise nightclub in a plunging, skintight, nearly sheer black evening gown, Cesca is lit up like an electric sign, high on her own beauty. She fixes her feverishly bright eyes on Guino’s face as she sways in front of him, turning to show her naked white back. She looks stripped to the bone, recklessly exposed. When Tony sees her dancing with another man, he drags her home in a jealous fury, tearing her dress and slapping her. But he can no more control her than he can control himself; they are both fueled by the same blaze of raw nerves and flammable energy. Poppy and Guino, by contrast, are both sleekly impassive and guarded, but finally unable to resist the Camontes’ insatiable appetites.