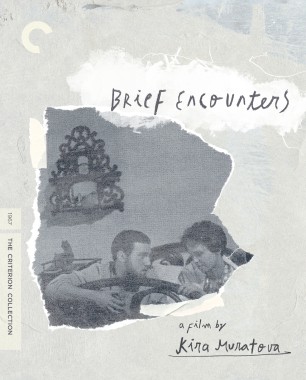

Two Films by Kira Muratova: Restless Moments

The first film that Kira Muratova directed by herself opens on herself, talking to herself. In Brief Encounters (1967)—which she made after codirecting a couple of features with Aleksandr Muratov, her then husband—Muratova plays Valentina, a bristly Odesa city planner on the promotion track within the hierarchy of the regional council where she works. Valentina has a husband she loves, even though he is usually absent. She has a high-status job she is good at, even if some of the men on the construction sites she administers bridle at being bossed about by a woman. And she lives in a spacious apartment, into which the luxury of a private phone line has just been installed. She ought to be, with only minor disclaimers, the very model of 1960s Soviet contentment. And yet, here she is, padding about her home at night, winding clocks, snapping lights on and off, checking the ticking of her watch, drumming a pencil on a pad. And all the while, talking to herself.

This is how we slide into the intimate spaces of this strange, restless film—like a note on white paper slipped noiselessly under a door. And it is our stealthy route into not just this one movie but a whole strange and restless body of work, across which Kira Muratova appears less concerned with making her ideas intelligible to some notional viewer and more involved in carrying on a mercurial, witty, inquisitive dialogue with Kira Muratova. In herself, she seemed to find her most encouraging ally and her most sardonic critic, and yet she also knew just when to listen to the counsel of neither and do whatever it occurred to her to do, apparently without analysis, guided only by a confidence in her instincts so complete that it was a kind of genius. And then—almost as an afterthought, and sometimes long after a film has been completed, and in several cases banned and eventually unbanned—we get the surreptitious pleasure of eavesdropping on a brilliant conversation that is never, not once and not even remotely, compromised for our consumption. In a 2016 interview with Russian magazine Seance, she said: “Well, sure, I’d like to show [my films] to my friends, to please someone, to have a kind of life circling around them. But if there’s no such life, this isn’t important . . . I have always worked to be satisfied with myself.” Muratova made movies like no one else because she made them for no one else.

This single-mindedness belies a retrospectively complex origin story. Muratova, now considered a Ukrainian filmmaker, was born in 1934 in what was then a part of Romania and is now in Moldova, to a Russian father and a Jewish Romanian mother. She studied directing at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in Moscow, before moving to Odesa, where she made movies for the famed Odesa Film Studio spanning the Soviet and post-Soviet eras—indeed, her 1989 cornerstone, The Asthenic Syndrome, has been called the last Soviet and the first post-Soviet film. But right from the start, absolutist classifications sat uneasily on Muratova’s work, which could not then and cannot now be straightforwardly grouped alongside that of her better-known—and often far less prolific—contemporaries Andrei Tarkovsky, Elem Klimov, and Alexei German. And even those comparisons that her style seems actively to court come apart on closer examination. She may favor, for example, the discontinuous edits, asynchronous sound, and avant-garde framing that characterize the films of French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard, whom she greatly admired. But Muratova’s motivations are different from Godard’s. She uses these devices less to discomfit the audience or disrupt their interaction with her work—because, again, she is not thinking overmuch about the audience—and more as a kind of dazzling shorthand for the way the imagination leaps and stutters, catching and losing its drift. It’s as though formal experimentation were simply the most expedient way for her filmmaking to keep pace with the intricate and dexterous running commentary provided by her own creative interior monologue.

So, if Brief Encounters is, loosely speaking, Muratova’s most accessible film, it is only because it is the start of that career-spanning conversation and she is making her introductions. Like Valentina wandering the rooms of her apartment picking up this thing, setting down that thing, Muratova moves through Brief Encounters as though making herself acquainted with the furnishings of her chosen profession, only to become immediately impatient with them once they start to feel familiar, and to look for ways to make them exciting again. And so what is the simplest of plots—a love triangle among Valentina; her geologist husband, Maksim (popular singer Vladimir Vysotskiy); and Nadya (Nina Ruslanova), the country girl Valentina hires as a housekeeper—is feathered and fluted into a far more elusive experience, purely through Muratova’s filigree filmmaking. Single scenes contain folds within folds, in which delicate repetitions and allusive digressions flourish despite an outward register of robust, chatty naturalism. A visit to the hair salon is a case in point, playing out on multiple planes at once: gossip about failed romances and feckless sons burbles on the surface while the camera sneaks portraits of the cackling hairdresser, mirror-image diptychs of the manicurist, and oddly lovely cutaways of hanks of hair being swept up from the salon floor. Within this hubbub, Valentina, her curlers snug under a hairnet, drifts into a reverie. A plinky piano tune (by Muratova’s composer for these two films, Oleg Karavaychuk) swells as she remembers that time when she and Maksim boiled shrimp for dinner, and the memory is served up to us from an impossible vantage point, looking out from under the water that simmers in the pot. Shrimp boiled, hair curled, daydream dreamt, Valentina pays and leaves the salon in a cheerful mood. But we stay awhile, listening to the staff snipe about her behind her back. “Isn’t she just an ordinary woman? But she acts like she’s special,” sneers the hairdresser. “She’s not special at all,” replies the manicurist, pursing her lips.