Of all the major Hollywood studios, Columbia may be the hardest to pigeonhole. Paramount evokes continental sophistication and Warner Bros. is synonymous with tough, ripped-from-the-headlines urban drama, but Columbia resists easy labels. In part, this is because the studio relied less on contract stars and directors and more on borrowed talent and short-term deals. The few stars truly fostered by Columbia had an outsize but temporary influence: in the 1930s, Jean Arthur helped make the studio a leader in screwball comedy; in the forties, musicals and film noir flourished thanks to Rita Hayworth. At the start of the fifties, as the studio entered its most glorious period, another dazzling comedienne arrived: Judy Holliday made six films at Columbia, starting with Born Yesterday (1950), in which she repeated her stage triumph as Billie Dawn.

Born Yesterday is a political satire and a romantic comedy, but above all, it is a makeover movie with a twist, following a woman who surprises everyone not with a new look but with an awakened mind. Billie is the pampered but bullied mistress (officially “fee-AN-cy”) of a crass millionaire junk dealer; when he comes to Washington, D.C., to buy a tame congressman, he makes the mistake of enlisting a journalist to take the unschooled Billie in hand. Rather than polishing her etiquette, he introduces her to ideas that crack her protective shell of ignorance and reveal a lively brain spoiling for a fight against corruption and exploitation.

Opening on Broadway in 1946, Born Yesterday became a monster hit, eventually running for 1,642 performances and prompting a bidding war for the rights among Hollywood studios. The winner was Columbia Pictures, whose president, Harry Cohn, paid a whopping $750,000 for the play. There was some kind of poetic justice in this, since playwright Garson Kanin admitted that the character of Harry Brock, the blustering tycoon with fascist overtones, was partly based on Cohn, whose reputation as a vulgarian and a tyrant exceeded even that of his fellow Hollywood moguls. Far from being bothered by the likeness, the shrewd Cohn may have been flattered, and he first sought to cast a major star, preferably Humphrey Bogart or James Cagney, in the role. Broderick Crawford got the part after winning the Academy Award for Best Actor for All the King’s Men (1949), which also earned Columbia its first Best Picture award since Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take It with You (1938). Both films were based on Pulitzer Prize winners (Robert Penn Warren’s novel and Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman’s hit Broadway play, respectively), and they set the studio on a fruitful hunt for more literary gold.

If Harry Cohn inspired Harry Brock, his studio was more like the underestimated Billie Dawn. Founded in 1918 and taking the name Columbia in 1924, it was known for churning out low-budget shorts, series, and B westerns. Even after Capra elevated the studio’s profile in the thirties, it was viewed as a short step above Poverty Row, the “Siberia” to which richer studios such as MGM loaned out their stars to humble them when they got hard to handle. But in the 1950s, while its rivals struggled, Columbia entered a golden age. As rising production costs and shrinking audiences made low-budget movies less profitable, the studio adapted nimbly, releasing a string of prestige movies that racked up box-office records, awards, and critical bouquets, including three more Best Picture winners: From Here to Eternity (1953), On the Waterfront (1954), and The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). Columbia had several advantages over its peers during this turbulent decade. Unlike most of the major Hollywood studios, it had never owned its own theater chain, and so was unscathed by the 1948 Supreme Court decision (known as the Paramount Decree) that ruled this practice illegal. And while much of Hollywood panicked at the threat from television, Columbia was one of the first studios to go into TV production, turning the enemy into a source of revenue.

The company also followed the trend of the times by enticing audiences back to theaters with movies that offered what the small screen couldn’t. But its biggest successes did not rely so much on Technicolor, 3D, or spectacle, as other studios (and occasionally Columbia itself) did with bloated Biblical epics and special-effects-laden creature features. Instead, it banked on the cultural cachet of its sources, stellar performances, and taboo-busting adult themes. The Motion Picture Production Code was loosening its iron grip on Hollywood in the fifties, and the pugnacious Cohn did much to chip away at it, from his determination to adapt James Jones’s From Here to Eternity, considered an unfilmable novel for its sexual frankness and criticism of the army, to his victorious fight to keep the sexist epithet broad in the dialogue of Born Yesterday.

The crude term bounces off Holliday, who turns the stereotype of the dumb blond into a brilliantly unconventional performance of sly wit and kabuki-like stylization, adorned with vocal gymnastics that range from falsetto whines to foghorn bellows, from cracked, off-key scatting to throaty screeches that could strip wallpaper. William Holden, whose services were shared by Paramount and Columbia from 1939 through 1955, found his trademark—the cynical golden boy gone to seed—at the former studio, but he was never more irresistible than as the bespectacled columnist who tutors Billie and falls for her. His ease with a wisecrack and his effortless sex appeal spice up the character’s didacticism, and seduce us into believing that an intelligent person can still be idealistic about American democracy. Though the film’s optimism may look quaint in the twenty-first century, the script feels startlingly current in its concerns about the dangers of ignorance, how loudly money talks, and how, as Holden’s character says, “selfishness can get to be a cause, an organized force, even a government.” Kanin himself observed that when he wrote the play, it was a fable, “but after Watergate, it became a documentary.”

Filmed partly on location, Born Yesterday provides a tour of Washington’s most stirring monuments, but Cohn’s primary wish was for the film to resemble the stage production as closely as possible. At his urging, director George Cukor took the unorthodox step of having his cast perform the screenplay in front of audiences drawn from Columbia staff, in order to gauge where the laughs fell and help the actors perfect their timing. The mostly wordless scene where Billie and Brock play gin rummy—and she wipes the floor with him—is precise as a Swiss watch.

Theater and movies have always had a rocky sibling relationship, and film versions of plays and novels have been disdained as middlebrow by champions of “pure cinema.” But Columbia’s prestige productions, based on stage hits and best-selling books, offer a fascinating study in adaptation and the array of approaches to transposing from proscenium to screen, or from page to camera.

Joshua Logan’s 1955 film of William Inge’s play Picnic is opened up with a vengeance, shot mostly outdoors on expansive Kansas locations, while Daniel Petrie’s 1961 version of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun takes place almost entirely on a single set representing a cramped three-room apartment. In each case, the choice is right. Inge’s play about small-town repression and snobbery, thrown into high relief by the arrival of a sexy drifter, can feel dated in its portrayal of women who think and talk about nothing but men. But the film gains tactile realism and sensuous warmth from the scuffed wood-frame houses and green parks dusted with late summer sun, lensed in glowing color by the great cinematographer James Wong Howe. Balancing the hysteria of Rosalind Russell’s desperate spinster schoolteacher and the palpable discomfort of William Holden’s objectified hunk are the grandeur of grain elevators looming like alien monuments, and the gorgeous melancholy of Kim Novak, who Logan said “bore her extraordinary looks like a physical disability.”

A Raisin in the Sun is about a Black Chicago family whose tensions and frustrations are exacerbated by the claustrophobic tenement flat where three generations live on top of one another—with a shared bathroom in the hall. Hansberry’s groundbreaking play, the first by a Black woman to open on Broadway, tackles housing discrimination, abortion, and generational conflicts, embedding these issues in the texture and rhythms of daily life. In the film, scenes unfold in long takes and medium shots that keep most of the players in the frame, including those on the sidelines; we are forced to stay in the middle of the family’s anguished arguments and confrontations, aware of every reaction, perspective, and shifting current of feeling. The film preserves almost the entire cast of the original Broadway production: Sidney Poitier at his most electric, kinetic, and furious; Ruby Dee in a devastating portrait of quiet, worn-down stoicism; and Claudia McNeil as the tree-of-life matriarch. The camera grants an intimacy the stage could not, letting us see the tear-tracks and winces, for instance in a lacerating exchange between Poitier’s character and his mother, when he tells her that money is life. “Once freedom was life, now it’s money,” she sighs, to which he bitterly retorts, “It was always money, we just didn’t know it.”

If A Raisin in the Sun calls for unvarnished simplicity in its presentation, Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly, Last Summer demands a combination of baroque style and straight-faced conviction. Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1959 film manages to preserve the play’s allusions to incest, rape, homosexuality, and cannibalism, as the lushly lurid story moves between insane asylums and a New Orleans mansion set in a jungle garden (shot in a London studio). The home’s doyenne, Violet (Katharine Hepburn), descends upon guests via a cage elevator, seated in a flowing gown and chattering like a demented goddess. References to flesh-eating are seeded throughout, from the garden’s Venus flytrap to a gruesome story of birds devouring baby sea turtles to the accusation that Violet and her son, Sebastian, “fed on life.” Violet wants to lobotomize her niece Cathy (Elizabeth Taylor), to stop her from talking about how her adored son really died the previous summer. The whole play revolves around this absent character, variously described as a martyr and a predator, saint and sinner, pure poet and decadent cynic. If Sebastian did appear, could anyone possibly have played the role? Perhaps, in his younger days, Montgomery Clift—but by this point substance abuse and ill health made him barely employable, and his friend Taylor got him the part of the kindly doctor who helps the traumatized Cathy. His fragility, unexplained by the text, adds an intriguing wobble to the script’s overwrought contrivance.

Six years earlier, Clift was at his pinnacle in From Here to Eternity, playing Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt, a proud and stubborn soldier who endures bullying for his refusal to join the division boxing team. Director Fred Zinnemann was determined to cast Clift, finally telling Cohn (who wanted Aldo Ray for the part) that he would not do the film without him. One can’t blame Cohn for being dubious: with his delicate beauty, sensitivity, and slouchy, rail-thin build, Clift was no one’s idea of a boxer or a military man. But while plenty of actors could project toughness and integrity, no one else had the inner radiance that convinces us of Prewitt’s quiet strength, the soul that seems to shine through his eyes like a diamond.

The film is a sprawling ensemble piece about an army unit in Hawaii in the days leading up to Pearl Harbor. It was shot in black and white to save money, but the choice was fortunate, keeping attention on the actors instead of the colorful splendor of beaches and loud Hawaiian shirts. The screenplay by Daniel Taradash divides its time between Prewitt, Sergeant Warden (Burt Lancaster)—embroiled in an adulterous, surf-splashed affair with his commanding officer’s wife (Deborah Kerr)—and the irrepressible, hotheaded Maggio (Frank Sinatra, in a vibrant performance that revived his slumping career). But Prewitt is by far the richest character, a man of rare talent whose deepest principles of individualism and conscience (“A man don’t go his own way, he’s nothing”) are in terminal, self-destructive conflict with his devotion to the army, which demands adherence to the group and obedience to the rules. Clift decided that the way to play Prewitt, whom he considered “a limited man of unlimited spirit,” was to give away as little as possible, and he trimmed his own dialogue and underplayed dramatic scenes, resulting in a performance whose force is channeled through a narrow opening, like the pure wail of the bugle he plays.

Burt Lancaster said that when he filmed his first scene opposite Clift, it was the only time in his career that he could not stop his knees from shaking: “He had so much power, so much concentration.” Clift worked out, studied boxing and bugling, and forged a close, bibulous friendship with James Jones, who had based his novel partly on his own experiences in the army. To obtain cooperation from the military and permission to film on location in the Hawaiian barracks, Columbia agreed to soften Jones’s harsh critique: where the movie’s despicable Captain Holmes is forced to resign for encouraging the hazing of Prewitt, the book’s equivalent is promoted.

A more uncompromising attack on the military mind came in David Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai. Its source was a 1952 French novel by Pierre Boulle, who had been a prisoner of war in Indochina and created a fictionalized account of a Japanese prison camp in Thailand and the building of the Burma-Siam railway, during which some 13,000 Allied prisoners died. Independent producer Sam Spiegel, who purchased the rights, had forged an arrangement under which Columbia financed and distributed his films, including On the Waterfront; Suddenly, Last Summer; and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Such deals with independents were common at the studio, even though it was hard for Harry Cohn, the only studio president who also acted as head of production, to surrender control. He would call a screenwriter in the middle of the night to query a single line in a script, and Zinnemann recalled how he “constantly got into our hair . . . worrying about casting, wardrobe, and locations.” Cohn had a fit when he discovered that there was not a single white woman in The Bridge on the River Kwai, and demanded the insertion of a scene where William Holden’s escaped POW enjoys a dalliance with a blond nurse on a tropical beach.

The original script was written by Carl Foreman, who was blacklisted in Hollywood and working in the United Kingdom. Lean detested this screenplay, which he thought reduced the story to superficial action-adventure, and brought in another blacklisted screenwriter, Michael Wilson, to work with him on revising it. Since neither man could be named, the screen credit—and the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay—were given to Pierre Boulle, who did not speak English and had no involvement with the film. (Eventually, the credits were revised to name Foreman and Wilson.) It was Lean and Wilson who rewrote the character of Colonel Saito, the commander of the POW camp, changing him from a drunken, raving villain to a flawed human trapped in a rigid code that brands failure as disgrace. In his last great performance, former silent-movie idol Sessue Hayakawa viscerally embodies Saito’s frustration and shame as he loses a battle of wills with the martinet Colonel Nicholson, commander of a newly arrived group of British prisoners.

Spiegel talked a reluctant Alec Guinness into playing Nicholson, and while Bridge’s hero is William Holden’s antiheroic American, Shears, the complexity of Nicholson is the watch-spring driving this three-hour wide-screen epic. He is a good officer loved by his men, but also a stickler so inflexible that he is willing to consign himself and his men to suffering and death for a point of order—namely the Geneva Convention’s provision that officers cannot be forced to do manual labor. Worse still, he is someone for whom war is a game and the letter of the law is more important than causes or consequences. Therefore, once he has won his skirmish about the rules, he sees no problem with throwing his best efforts into building the bridge the Japanese have struggled to complete. He has three motives: to boost morale and discipline among his men, to show up his captors with a smug display of British colonial efficiency, and to create a lasting monument as he confronts his own impending mortality. He succeeds in all three. It took eight months for crews on location in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) to build the wooden railroad bridge, and it is a thing of beauty. Its handcrafted elegance adds poignancy to the film’s climax, as Nicholson’s love for his bridge shades into obsession and madness, while a group of commandos including a reluctantly drafted Shears make their way through the jungle to blow it up.

Many people, including Guinness, felt that the conception of Nicholson was anti-British, though Boulle (like the London-based Spiegel, an avowed Anglophile) had been inspired by the complicated notions of honor he observed in collaborationist Vichy French officers. If Saito is an antagonist and also a double of Nicholson, so is Warden (Jack Hawkins), the leader of the commandos, another English gentleman whose soft-spoken, civilized exterior conceals a fanaticism that becomes a “stench of death,” as Shears puts it disgustedly. Every time Malcolm Arnold’s cheerful military march rises on the soundtrack, it sounds more bitterly ironic, finally blaring over a scene of utter waste. Harry Cohn, who notoriously claimed that his rear end itched when a movie went on too long, wanted to cut down The Bridge on the River Kwai, but Spiegel fought for every minute.

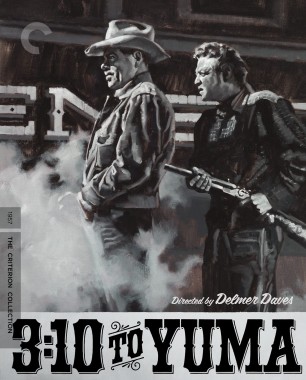

Throughout the 1950s, alongside its prestige projects Columbia continued to produce the smaller-scale genre films for which it was known, including a rich seam of film noir (In a Lonely Place, The Big Heat, The Reckless Moment) and some of the decade’s finest westerns, crowned by Budd Boetticher’s gracefully austere Ranown Cycle. Delmer Daves’s 3:10 to Yuma (1957) is relatively modest in scale—the heart of the film is a duel of wills and words between two men cooped up in a hotel room—but few westerns can match its visual beauty or its largeness of spirit. The source was a spare short story by Elmore Leonard about a deputy sheriff charged with getting a captured outlaw aboard a train in the face of his gang’s vow to spring him.

The film grants the two men equal time and leaves us to judge them. Glenn Ford, one of Columbia’s biggest male stars, gives his best performance as the intelligent outlaw, Ben Wade; he exudes cool confidence and easygoing charm, but the first thing we see him do is kill two men without batting an eye. The deputy becomes an ordinary rancher, Dan Evans, who takes the job out of desperation as his drought-stricken family faces financial ruin; Van Heflin plays him without an ounce of glamour, slowly laying bare the grit beneath the nervous sweat. As they wait for the train and the likely fatal showdown it will bring, Wade tries to bribe, frighten, and humiliate his captor, but ends up forced to respect Dan’s bravery and decency, and perhaps even envy the family man with the loyal, loving wife. The script’s humanism is enriched by the exceptional beauty of the black-and-white cinematography: the low, hard winter light raking across a bleached landscape, throwing slanted shadows and shining through dust and steam. Recurring crane shots that float down to or rise up from the earth take in the lonely emptiness surrounding the characters. Many westerns pay lip service to the wish that problems could be settled by some means other than guns, but 3:10 to Yuma stands as one of the only entries in the genre that can actually imagine an alternative to climactic violence.

Harry Cohn died in 1958, but the studio that he built and bossed survived him; he would surely relish the fact that in the twenty-first century Columbia, as a subsidiary of Sony Pictures Entertainment, occupies the former lot of MGM. His death came at a moment when all of the original Hollywood studios were floundering amid a barrage of economic, technological, and cultural changes; the sixties would bring frantic efforts by the old guard to appeal to the youth market. Many of Columbia’s best films from the fifties seem less dated than what followed, because they sprang from an earnest if sometimes compromised effort to make movies for adults: movies that acknowledged ambiguity and disappointment, that dealt with moral conflicts and awakenings; movies that were ambitious and serious in ways not always “cool.” Even viewed on the small screen, these films are—in the best way—big.

More: Features

Galatea’s Revenge: Actresses Talk Back

In a collection of behind-the-scenes documentaries now playing on the Criterion Channel, legendary female performers assert their agency over their screen personae and find freedom in the glamour and artifice of their profession.

A Year’s Worth of Essential Reading

As we come to the end of 2025, we’re looking back at some of the essays and interviews we’ve shared with you over the past year.

Room Tone 2025

Celebrate the holiday season with this special treat from our production team.

Dying Worlds: Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Dramas of Cosmic Disorder

The director of Rat Trap and Monologue was an uncompromising artist who helped establish the Indian state of Kerala as a hub of bold political filmmaking.