Into the Groove: A Conversation with Susan Seidelman

Throughout her four-decade career as a writer and director, Susan Seidelman has told complex stories about unconventional women striving to express themselves and maintain their autonomy. Her genre-melding films fuse a passion for the pleasures of Hollywood spectacle with a playful punk ethos informed by the years she lived in downtown Manhattan in the midseventies.

Like many of the heroines she has created, Seidelman left suburban life for the allure of the bohemian city. After high school, she enrolled in the film department at New York University, where she directed two short films that prepared her for making her debut feature, Smithereens (1982). A lo-fi blueprint for her subsequent portraits of women reinventing themselves, this gritty and glamorous 16 mm snapshot of a bygone era of New York life became the first independent American film to compete for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Its success placed Seidelman in the Hollywood spotlight and set her up for her next film, Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), a madcap New York odyssey that revolves around mistaken identity, starring a pre–Like a Virgin Madonna alongside Rosanna Arquette in her first leading role.

Smithereens

Desperately Seeking Susan

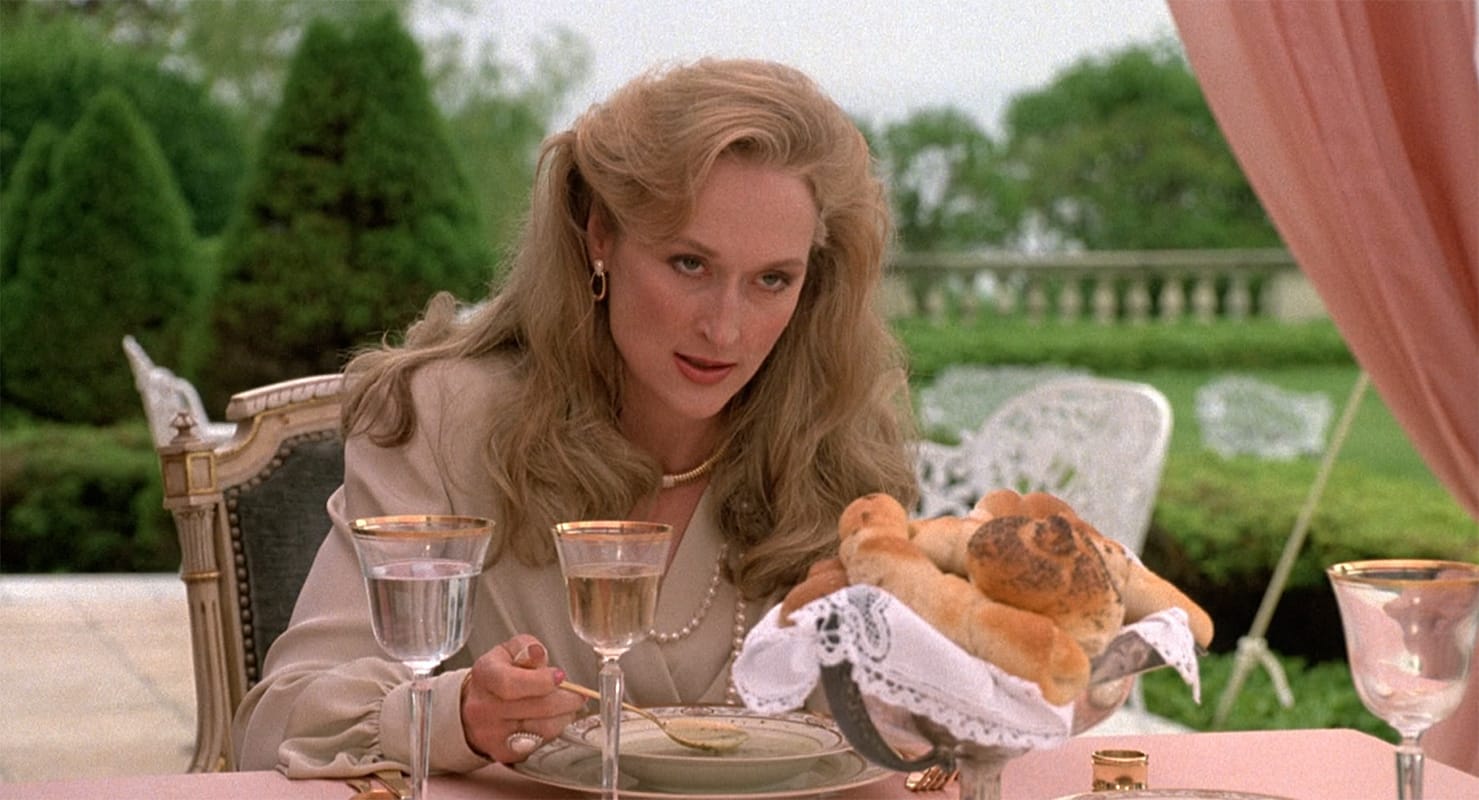

She-Devil

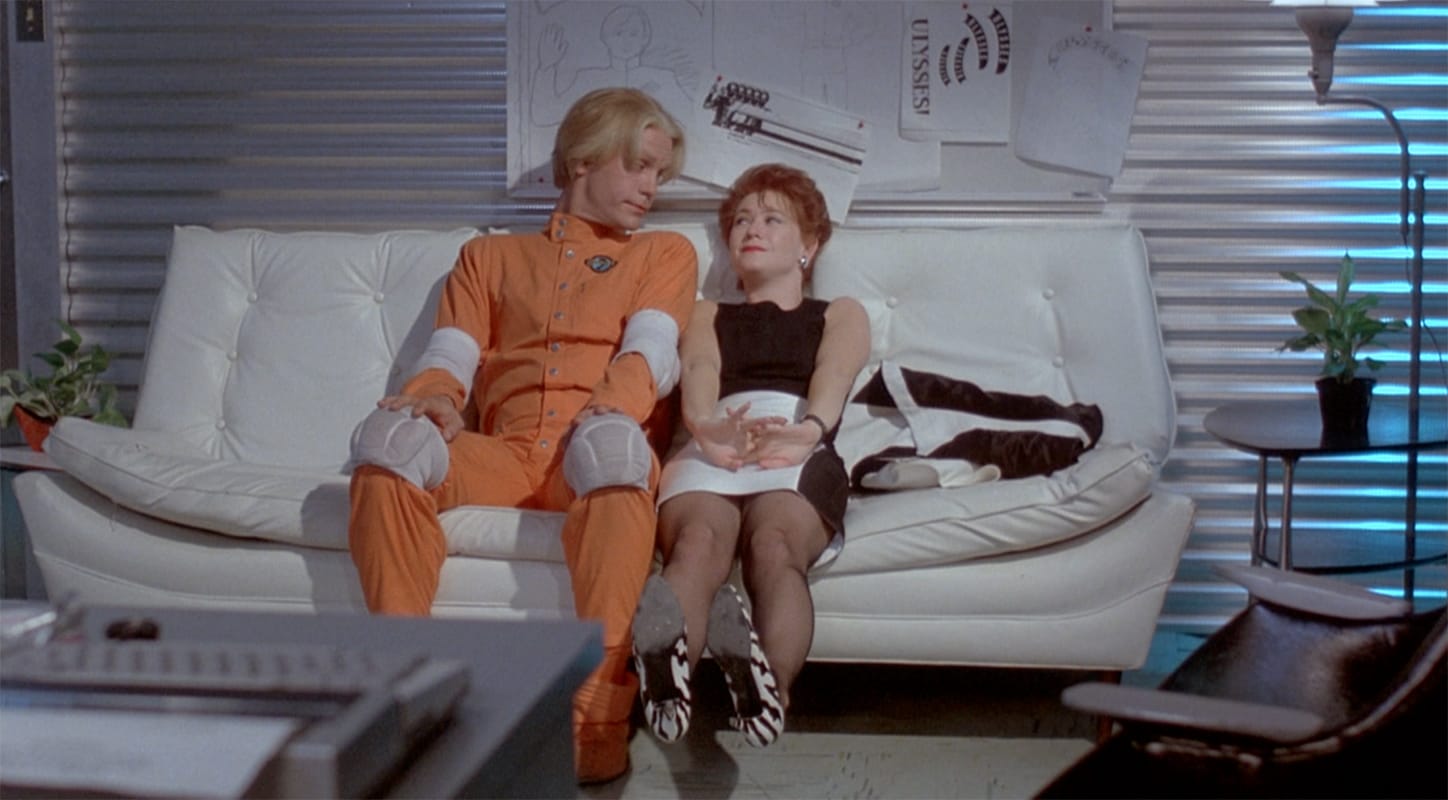

Making Mr. Right