Vengeance Is Mine

Over the years the cinema has given us any number of tales of the criminal underworld, and explorations of the mindsets of murderers. Yet for all that’s come before there’s been nothing quite like Shohei Imamura’s Vengeance Is Mine.

Based on one of the most sensational true crime stories of modern Japanese history, this startlingly violent melodrama recounts, in a simple dispassionate style, the story of Iwao Enokizu, self-styled “King of the Criminals.” A young man from a seemingly ordinary middle-class background, Enokizu began his criminal career through a number of petty graft schemes that had him in and out of prison on several occasions. In the mid-sixties, however, he committed a series of murders that made headlines and startled all Japan with a sense of uneasy fascination. A nationwide manhunt resulted in his capture in fairly short order. But between the time of the murders and his arrest it was discovered that Enokizu had engaged in a number of fraud schemes—posing as a lawyer and bilking gullible families out of their bail money.

How do you present a monster like this on screen? Certainly not by making apologies, or boiling things down to simple, convenient sociopathological explanations. Director Imamura and his collaborators have no such thing in mind. Enokizu’s crimes are shown with directness and simplicity that deprive them of any sense of excitement or glamour. Imamura’s camera doesn’t avert its gaze from the squalid messiness of cold-blooded murder. At the same time, scriptwriter Masaru Baba doesn’t offer easy outs by making such classically “senseless crimes” make sense.

We’re given a clear picture of Enokizu’s home life—particularly his stormy relationship with his father. A flashback discloses an important incident during the war when Enokizu’s father allowed himself to be disgraced in public at the hands of the authorities, before his son’s horrified eyes. This clearly triggered a rebellious attitude in the boy that led to his later criminal career. But as Imamura shows it, this incident isn’t meant to carry that much weight. Likewise his father’s attraction for Enokizu’s wife (shown in the disturbingly erotic bath scene in Chapter 7) doesn’t explain things either. There is no simple way to understanding why Enokizu turned out as he did.

Imamura is helped enormously in bringing Enokizu’s story to life by the performance of Ken Ogata in the leading part. One of Japan’s best actors (he played the title role in Paul Schrader’s Mishima), Ogata never distances himself from the part. He’s right inside Enokizu’s skin from first moment to last. And though we may never come to truly understand what makes this maniac tick, Ogata displays the cocky authority that made Enokizu’s murder and larceny spree possible.

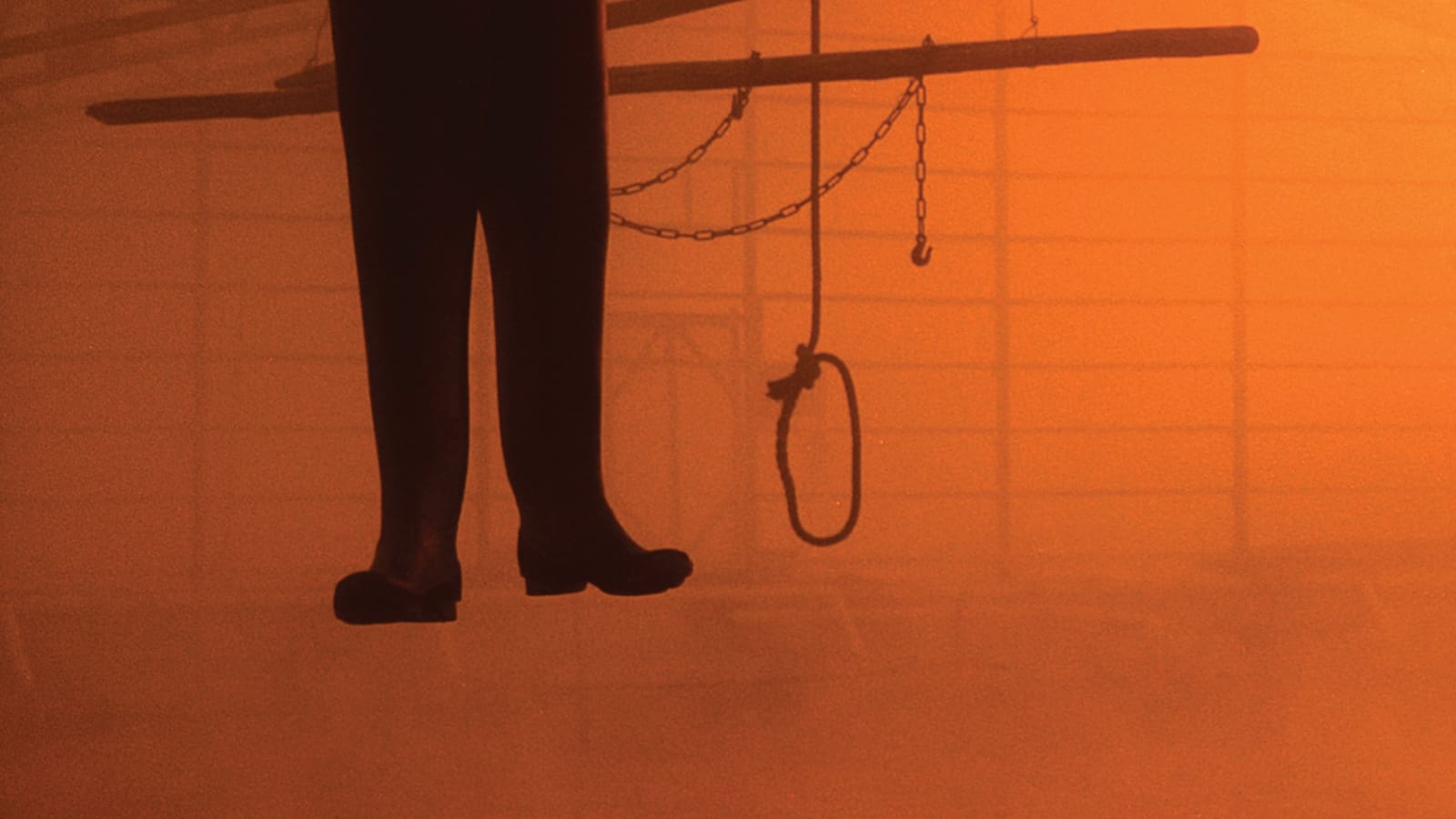

The ease with which Ogata moves through the role is especially important in the film’s last part. Hiding out in a cheap “hot bed” hotel in a small town, Enokizu begins to have an affair with its landlady (Mayumi Ogawa). After the frenzy of crime and killing Enokizu seems to be taking a hiatus. He seems to care, in his own way, for this woman. And she in turn appears taken with him. When she learns of his identity she isn’t moved to tell the authorities. For a brief moment the story looks to be taking a Bonnie and Clyde turn. But just as quickly, Enokizu reverts to type -- destroying even this bit of kindness and sympathy. It’s shocking, and it’s saddening, but it’s not without its logic. However, as Imamura moves from this toward the film’s finale we’re not left unaware of the tale’s true purpose. Vengeance is Mine has no wish to make sense of a “senseless crime,” it only wants to make “senselessness” palpable. And that it does—to devastating effect.