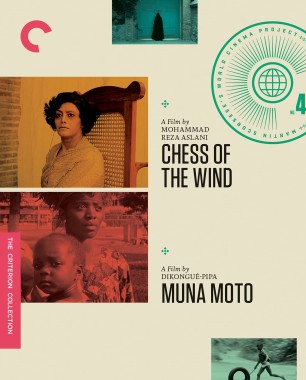

Chess of the Wind: The Glorious Miniature of an Upheaval

When Chess of the Wind premiered in November 1976, at the fifth Tehran International Film Festival, nobody knew what to make of it. A mix-up in the order of the reels at the first of three screenings—either a technical issue or a deliberate act of sabotage—made the plot almost unintelligible, while faulty projector lamps meant that the interior scenes, certain of which are artfully lit using candlelight, appeared so dark that viewers became angry. Moreover, despite the film’s historical setting—the drama unfolds in a feudal mansion, following the death of a matriarch—this tale of deceit and intrigue was a little too close to the bone for a society that had become increasingly polarized since the beginning of the seventies. Complete with breaks in the fourth wall, a delicately handled lesbian scene (the first of its kind in Iranian cinema), and an ending in which a working-class woman overthrows a male-dominated household and liberates herself, this enigmatic work was both perplexing and reflective of a changing Iran.

Equally baffled was the film’s thirty-two-year-old director, Mohammad Reza Aslani, when he faced questions during a hostile press conference (another filmmaker, Basir Nasibi, later called it a “press prosecution”) and realized that the film had not been understood at even its most basic formal level. A major jump in time that occurs toward the end of the narrative led one critic to question Aslani’s competence as a filmmaker. The daring ambiguity of the film was sheer abstraction to critics and audiences used to Iranian cinema’s rigid adherence to a realist tradition—any deviation from which could be easily condemned—and to the easy slogans of films posing as “socially minded.”

Owing largely to the initial poor reception of Chess of the Wind, a theatrical release in Iran never went ahead. The film’s producer claimed that it had been sold to five countries for international distribution, but in the interim the social unrest leading to the 1979 revolution put not only this film but also the entire industry on hold. After the revolution, due to the mandatory enforcement of the hijab, all prerevolutionary films depicting unveiled women were banned. Chess would not be screened again, inside or outside Iran, for the next forty-four years. Aslani was left disheartened. It seemed that the career of a blazing talent had ground to a halt before it had a chance to get started.