RELATED ARTICLE

Raging Bull: American Minotaur

The Criterion Collection

What was the “New Hollywood”? And is it a useful category or superficial shorthand? It’s arguably easy enough to make a case for the former: certainly, the history of American cinema now has the films and the directors to support the assertion that a strong current of visionary, personal filmmaking ran through the output of the dying studio system starting in the late 1960s, and ending after the memorable box-office debacle of Michael Cimino’s critically drubbed epic Heaven’s Gate (1980).

Perhaps the best-known chronicle of this era of filmmaking is Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (1998). A persistently dishy, multitiered tale of often hubristic behavior on the part of the filmmakers associated with the New Hollywood—Martin Scorsese, Paul Schrader, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Peter Bogdanovich, Cimino, and others—the book is cannily titled. It’s not just catchy wordplay: “riders” and “bulls”—hey, I get it! The two films it references are bookends of a sort, arguably the first and last triumphs (Dennis Hopper’s 1969 Easy Rider commercially and culturally, Scorsese’s 1980 Raging Bull artistically) of the period of American commercial cinema that Biskind recounts.

One gets the impression, from this chronicle and others, that the seventies into the early eighties was genuinely a time for filmmakers. The so-called movie brats—or, in Billy Wilder’s phrase from his trenchant envoi to Hollywood, Fedora (1978), “the kids with beards,” several of them products of the then relatively new phenomenon called film school—were as well-versed in film history and critical currents as they were in camera movement. They remembered how the old-school studio heads had mutilated Erich von Stroheim’s reputedly monumental Greed and dismembered Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons into a bottom-half-of-the-bill demi-masterpiece. In eventually extending to Scorsese, star Robert De Niro, and producer Irwin Winkler the freedom to make Raging Bull their way, was United Artists showing its artists that it had gotten religion? Had, as William Holden’s character in Fedora proclaims, the kids with beards actually “taken over”?

Not quite.

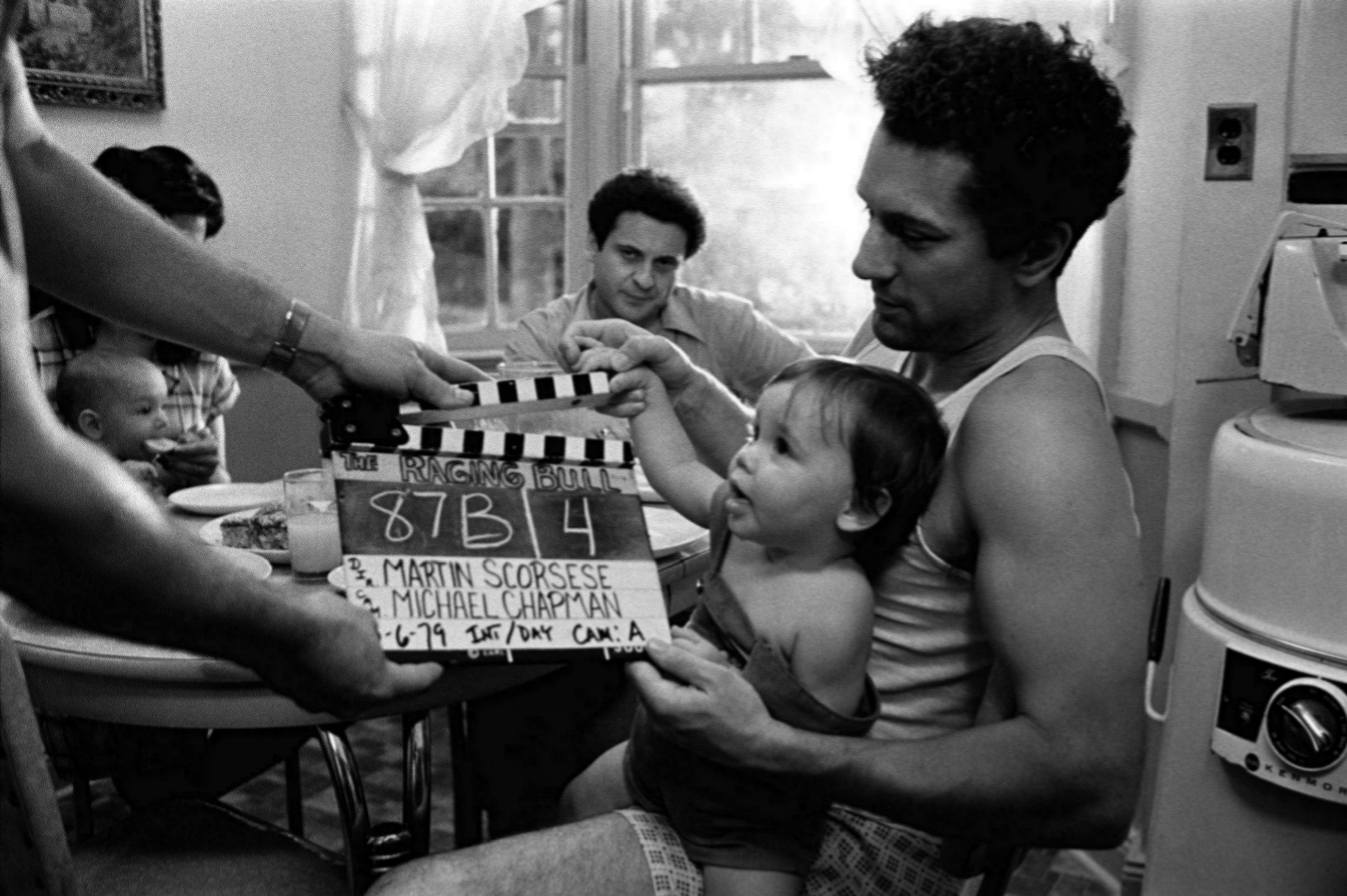

The story has been told many times, from several different perspectives. You may have read it in one form in Steven Bach’s account of the disastrous making of Heaven’s Gate and the subsequent implosion of UA, Final Cut (1999); in another, in Biskind’s book. It appears in Jay Glennie’s lavishly illustrated 2021 coffee-table book on Raging Bull. And it starts like this: after a long gestation period—De Niro had been wanting to make the film since 1974, when he read boxer Jake La Motta’s autobiography, coauthored by writers Peter Savage and Joseph Carter—Raging Bull was on its way to finding a home at United Artists.