RELATED ARTICLE

Black Girl: Self, Possessed

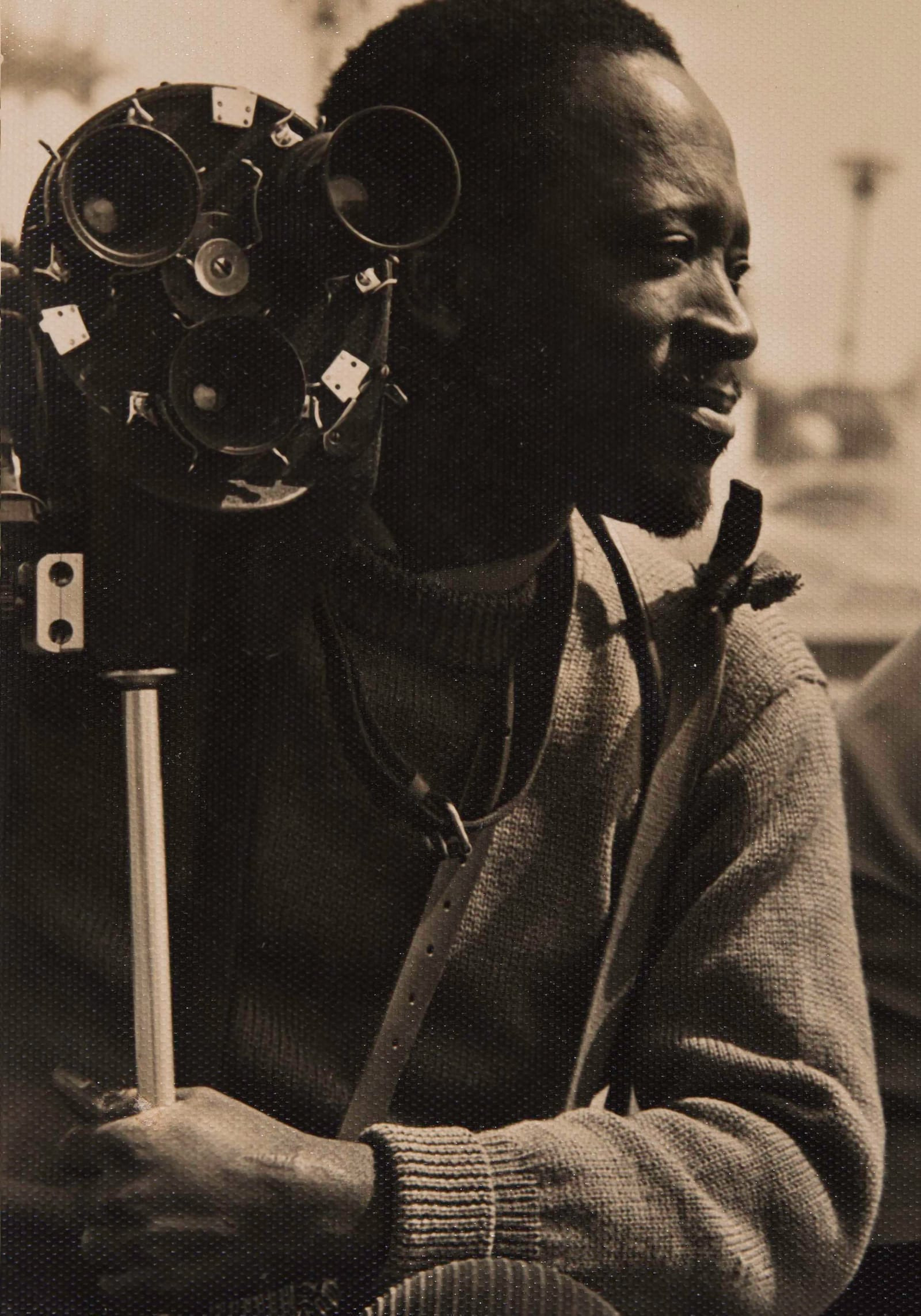

By Ashley Clark

The Criterion Collection

“Me myself, I prefer literature,” the Senegalese author-filmmaker Ousmane Sembène tells a group of African students in the 1994 documentary Sembène: The Making of African Cinema. “But in our time, literature is a luxury.” Sembène’s historical conjuncture—Africa’s putative transition from European-ruled colonies to independent nations—was long, and cinema, an art that could speak to illiterate people steeped in oral traditions, was the anticolonial tool that suited its protracted modulations. Released in 1968, Sembène’s second feature, Mandabi, mines that line between colonial and postcolonial, between cinema and the literary, and between languages too. The first feature made in an African language, Mandabi was shot in Sembène’s mother tongue of Wolof, the most widely spoken language in Senegal. The film was based on Sembène’s own 1966 French-language novella The Money Order. A careful and deliberate self-adapter, Sembène also drew on his previously published fiction for four other films: the shorts Niaye (1964) and Tauw (1970) and the features Black Girl (1966) and Xala (1975).

Sembène realized his ideas initially in a literary language but also in a foreign one. He published ten books in forty years. Most concern the problem of African liberation. His short stories, novellas, and novels were all written originally in French, a fact that Sembène felt betrayed the promise of the struggle for African freedom. By writing in a colonial language, he would never reach the population he was intent on not only representing but also awakening politically: people in rural areas, people who could not read, people who spoke Wolof—that is, most of the people of Senegal, who did not speak French but were part of an African oral tradition. Thus to write in French was implicitly to write for a specific audience: the francophone West and a small elite population in West Africa. Because of global capitalist interests and Senegal’s internal power politics, Sembène stood in opposition to both groups.

Though written in French, his previous novels—Ô pays, mon beau peuple! (Oh country, my beautiful people!, 1957) and God’s Bits of Wood (1960) especially—contained a widespread use of Wolof through neologisms and direct translations of vernacular expressions, paving the way for Mandabi. And the original volume featuring that film’s source novella includes a Wolof glossary of over sixty words. In Sembène’s literature, Wolof is almost a character in its own right, foreignizing the French text. Even in his early filmmaking, Sembène continued working in French out of necessity, finding ways to subvert the language. The script for Black Girl, for instance, was rejected by the film bureau of France’s Ministry of Cooperation for production funding. He managed to get support elsewhere, but only by agreeing to present the voice-over for the protagonist’s inner dialogue in French, not Wolof—a distortion that, thanks to M’Bissine Thérèse Diop’s haunting performance, ultimately heightens the film’s evocation of the main character’s alienation. Despite these struggles, Black Girl achieved success in the international market, emboldening Sembène to assume full control of his films, one result being the opportunity to make Mandabi in Wolof (though his funders still demanded that he shoot a French-language version simultaneously).