RELATED ARTICLE

My Kind of Clown

By Lulu Wang

Party Time in Fellini Land

The Criterion Collection

“Yes, life is a dream, but sometimes that dream is a fatal abyss.”

Wanda in The White Sheik (1952)

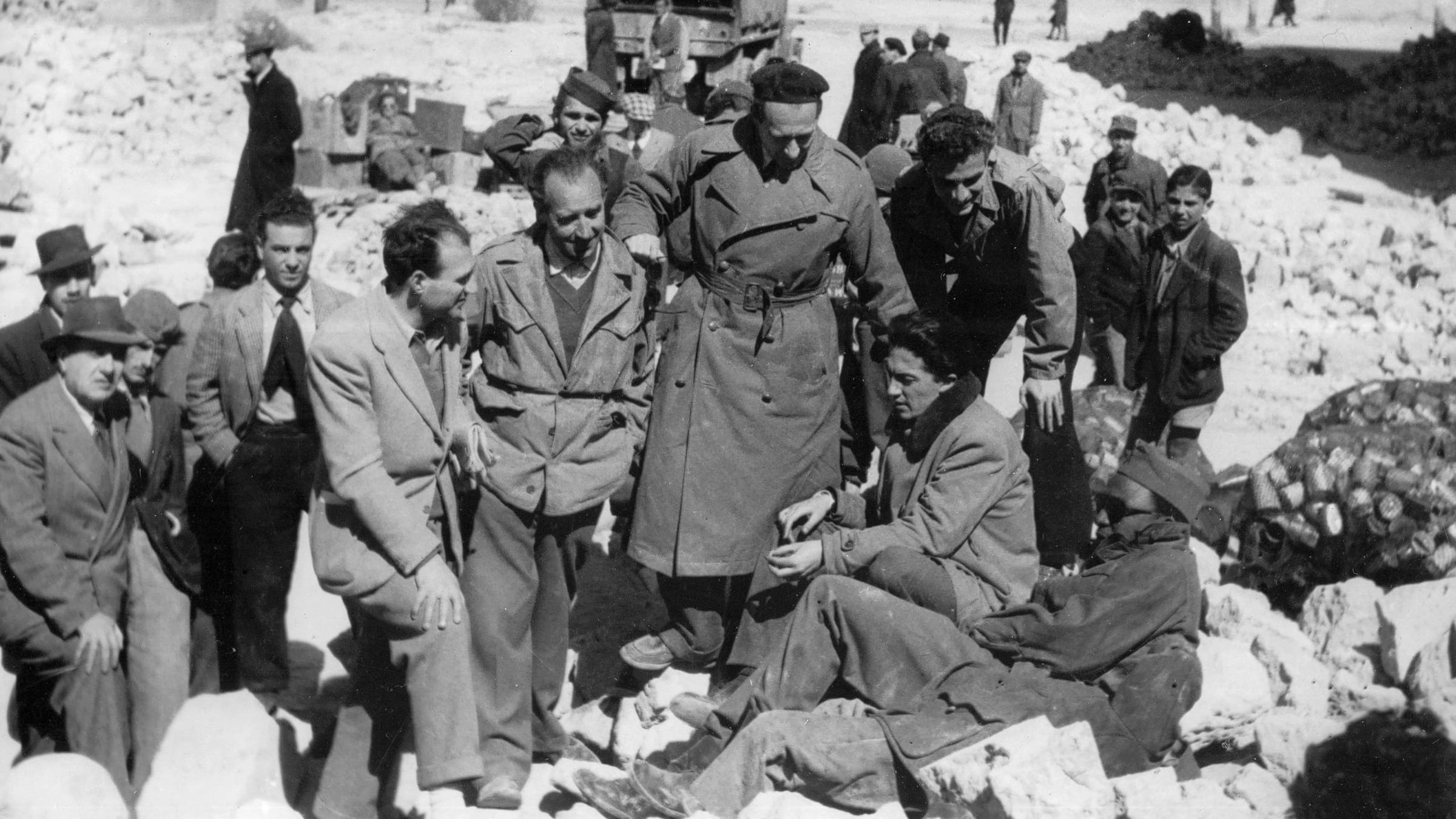

I have a vivid memory from the first film-studies class I enrolled in, a class on Italian neorealism, where the weekly screenings charted an evolutionary shift from the sober dramatic beauties of Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, and Luchino Visconti to the intoxicating comic energy of Federico Fellini, specifically images and sounds unleashed in La strada (1954). His fourth feature and first international success, La strada was confirmation that, after participating in Italian cinema as a screenwriter and director for nearly fifteen years, Fellini had assuredly found his voice and hit his stride. I was watching the film in the late seventies, almost twenty-five years after it was made, yet it wasn’t hard to recognize and yield to its ageless force, a freshness that felt unique. Every scene offers the pleasures of un-dressed locations and sharply observed behavior while presenting us with mythic archetypes engaged in eternal struggles, and every corner of the film brims with emotion.

At the risk of confiding too much, I can admit that my first engagement with La strada was elevated by delight in seeing Richard Basehart—the stalwart, fretful, red-haired submarine commander in Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, a faux-serious sixties TV show of my childhood—transported to a rural Italian circus, reincarnated in stark black and white as a japing, jabbering, high-wire-walking philosopher-clown, advertised by the circus barker as the Fool.

“And now the Fool will perform his most dangerous stunt yet. He will eat a plate of spaghetti while suspended 125 feet above the ground!”

The Fool falls from the wire, spilling the spaghetti and the table supporting it—but catches himself, flips, and stands on his head as onlookers gasp and marvel in the darkness below. This preposterous, death-defying display may serve as a concise metaphor for Fellini’s developing virtuosity as a filmmaker, as each successive project from the ensuing decades seems to spring fearlessly from one balancing act and breakthrough to another. The plate of spaghetti may not always survive intact; a film’s structure, or ostensible plot, gets sacrificed amid increasingly audacious performances; but life’s unstable essence—innocence and experience, generosity and cruelty, mystery and mortality—is captured and conveyed with a spirit that, resisting gravity, remains openhearted, daring, and radiantly affirmative.

La strada also marked my first exposure to a signature Fellini sound. Have you noticed the uniqueness, the aggressiveness, the implausible, high-pitched loudness of the wind in Fellini’s films?

Basehart’s Fool is vying with Anthony Quinn’s brutish strongman, Zampanò, for the Chaplinesque soul of Giulietta Masina’s Gelsomina. Fellini’s wind asserts itself in the trash-strewn town square, an open street framing a fountain, where Gelsomina, thinking she has escaped, is discovered by Zampanò late at night, among other homeless people with nowhere to go. The strongman drives up in his sputtering van, gets out, demands she get in, slugs her when she refuses (the camera angle makes the violence discreet), then repeats the demand. Over all this, the wind doesn’t let up. The sound is, of course, dubbed, like nearly everything in Italian cinema. That’s the persistent contradiction; even in neorealism, the naturalness of the image, the fluidity of the camera work, the aliveness of the actors—the overarching sense of truth—it’s all mitigated by inorganic sound inserted imperfectly after the fact. Fellini’s wind, in any case, is even more declarative and unconvincing than other aspects of Italian dubbing, and it seems to be the same looped sound effect recurring from movie to movie. An otherworldly wind, with roughly the same relation to real wind that Egyptian hieroglyphs bear to actual animals and plants. An infinite, high lonely susurration; an eternal, fairy-tale gasping. What it signifies, from film to film, can grade from longing to desolation to cosmic upheaval, a void emptying itself out into the world. In any case, you can count on it, the sonic quintessence of Fellini’s universe.

La strada is not Fellini’s first great movie—the preceding pictures are as visually resourceful and fine-tuned, as irresistibly human, and as laugh-out-loud funny at moments when a comic spirit kicks in. La strada was simply my first exposure to Fellini, and as such feels abidingly fundamental. Whirling within its story and style, the core elements of Fellini’s DNA are readily apparent.

In every Fellini picture, there is at least one scene involving a vaudevillian display of dancing, or song and dance.

At least one character in each film qualifies as a fraud, liar, or thief, and this swindler/trickster character usually wears distinctive headgear.

There’s at least one incident of infidelity per film, at least one boisterous group meal, at least one scene acknowledging, in a mocking or majestic fashion, the circuslike aspect of Catholic pageantry.

In each film, a character’s inner and outer reality are shown to be interwoven. These realities can be violently at odds, but somehow, within the arena of the movie, an uncanny convergence takes place, temporarily or as in an extended fever dream that devours rational boundaries. Over time, this convergence—the coalescing of real life (memory, history) and dream life (fantasy, cinema)—became Fellini’s dominant subject and theme.

“A large part of the beguiling comedy and depth of Fellini’s early films lies in the empathy he grants all his lost and desperate characters.”

“It’s as if Fellini is holding two mirrors face-to-face, the past and the present, with his beloved actors between them, confronting the inescapable curse: no one is ageless.”