RELATED ARTICLE

Godmotherly Love

The Criterion Collection

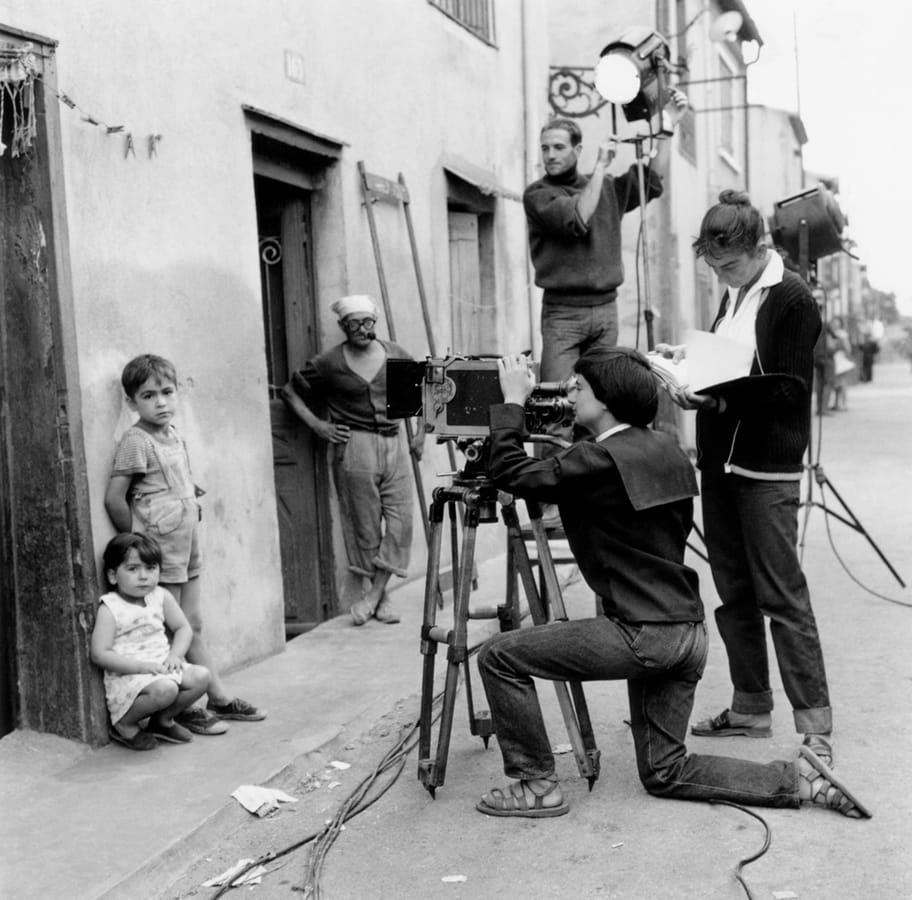

The poster for the seventy-second Cannes Film Festival, held in May 2019, used a photograph taken during the shooting of Agnès Varda’s first film, La Pointe Courte, in 1954. Wearing rolled-up trousers, a shirt, and a straw hat, the director stands barefoot on the back of a crouching male technician, looking intently into the viewfinder of a camera. The poster takes this image out of its original context to place it over a seascape in lurid orange and indigo, making Varda tower over the horizon. It encapsulates both her pioneering status as a female filmmaker in postwar France and the youthful, imaginative nature of her filmmaking.

For her own part, Varda tended to reject the category of “woman filmmaker.” In a 1962 interview, for example, she was adamant that a director’s gender was a “false problem.” She added, “A man finds as many problems as I do . . . What is difficult is to make free cinema.” But she did identify as a feminist, in a way that Alison Smith perceptively qualifies, in her 1998 book on the filmmaker, as “committed rather than militant.” And her films were, from the beginning of her career, imbued with her gendered perspective, her interest in the lives of women, and her singularity as an artist. She was well aware of the complexity of her position; as she explained in a 1976 interview with the Belgian feminist journal Les cahiers du GRIF, her work had always been concerned with showing how “a woman would look for her own image, her own truth, within the [heterosexual] couple,” with “dissecting clichés” and myths pertaining to women.

The Cannes tribute to Varda—who died on March 29, 2019, less than two months before the festival—represented recognition that was long overdue. None of her films had ever received an official jury prize there; she had to wait until 2015 to be given an honorary award. Yet from the very beginning of her career, influential critics saluted Varda’s work. In January 1956, Martine Monod wrote of the “birth of a cineaste” in her review of La Pointe Courte in Les lettres françaises. In April 1962, Jean-Louis Bory asserted in Arts, “Cléo from 5 to 7 is a masterpiece.” Around the same time, the film historian Georges Sadoul, also in Les lettres françaises, urged spectators to see Cléo if they wanted “a true film, a modern film, profoundly of our era.” It wasn’t truly until feminist critics, beginning with Sandy Flitterman-Lewis and her 1990 book To Desire Differently: Feminism and the French Cinema, explicitly inserted gender into the analysis of Varda’s work that she was put properly on the film-history map, and particularly that of the New Wave. Many other studies followed, and Varda is now regarded as the paradigmatic French female filmmaker. Her twenty-first-century films attracted a new generation of feminist scholars, epitomized by the North American online publication Cléo: A Journal of Film and Feminism, named in honor of Varda’s 1962 heroine.

Top of post: © Ciné-Tamaris.

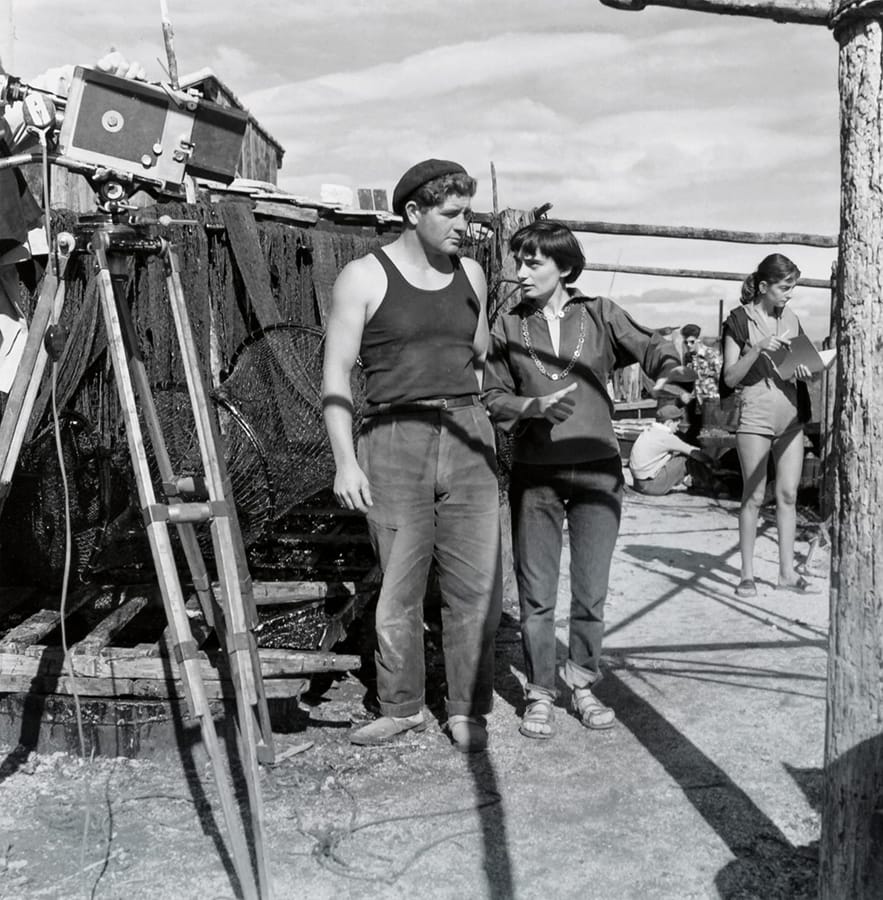

On the set of Cléo from 5 to 7. © Ciné-Tamaris.

Thanks to an artistic, bourgeois family background and studies in philosophy and art, Varda was steeped in painting, theater, and literature as a young woman. She began her working life as a photographer in Paris, including as the official photographer for the prestigious Théâtre national populaire (TNP). The period immediately after World War II, when Varda emerged as a young professional, was an exciting and contradictory time for women in France. As elsewhere, the war had accelerated the modernization of the country and the emancipation of women, who had finally been granted the vote in 1944. At the same time, the symbolic emasculation of a generation of French men by their traumatic defeat and occupation by Germany triggered a backlash against women. These tensions were evident, for example, in the fact that the late forties witnessed both Christian Dior’s regressively feminine New Look fashion and the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s groundbreaking feminist book The Second Sex.

“From her training as a photographer, she retained both a taste for documenting the world and a talent for inventive composition.”

On the set of La Pointe Courte. © Ciné-Tamaris.

“While Varda foregrounds the irreducible significance of the body to women’s lives, she never confines their identity to it.”