RELATED ARTICLE

The Milky Way: The Heretic’s Progress

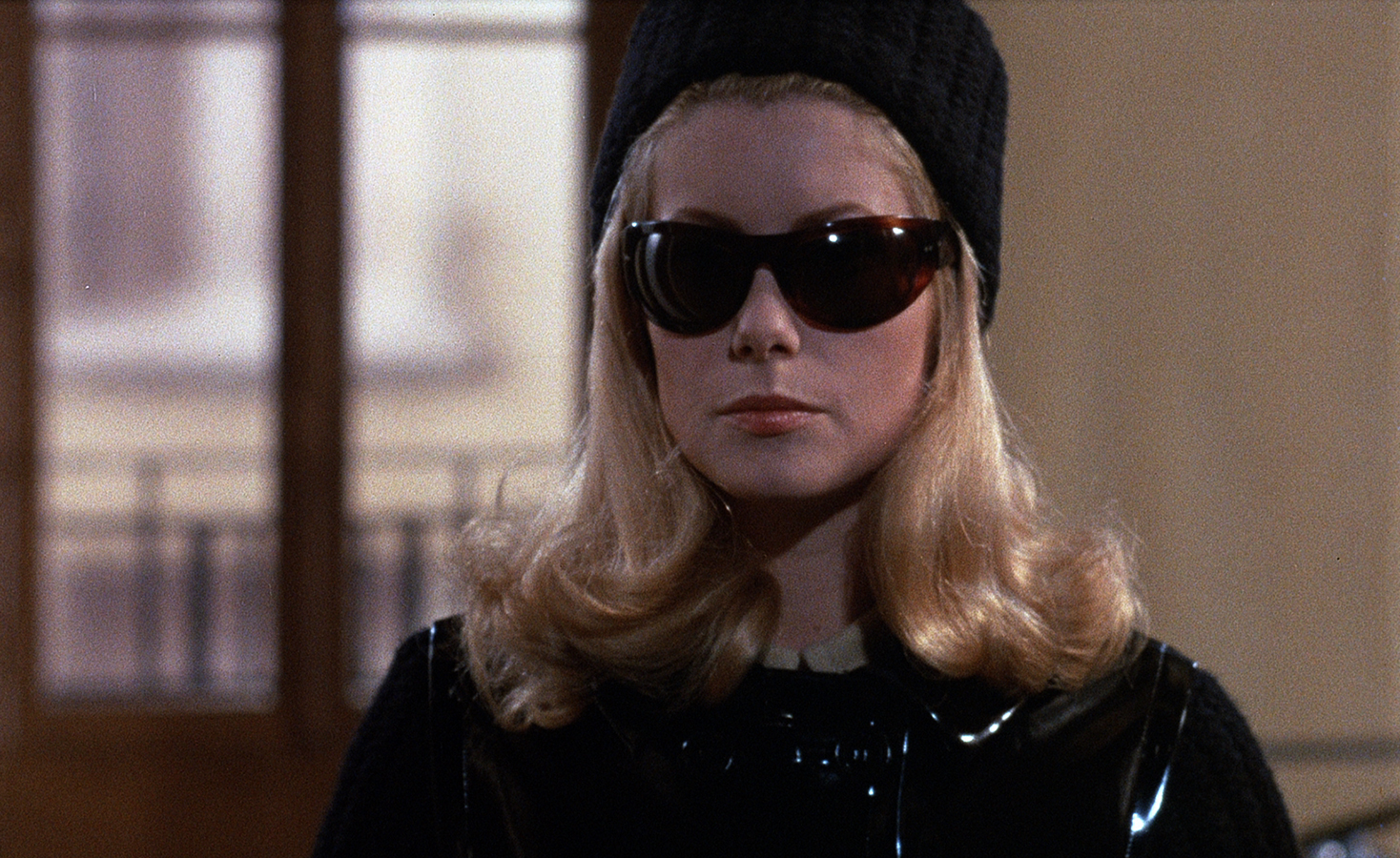

Belle de jour: Tough Love

The Criterion Collection

How many times, in cultural history, has surrealism been declared out for the count? For the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, writing in 1929, surveying the surrealist literature of André Breton, Robert Desnos, and Louis Aragon, the glory days of this predominantly French movement—which had started scarcely a decade earlier, in 1917—were pretty much already over. Thirty years after Benjamin’s pronouncement, the troublemakers of the Situationist International, led by Guy Debord, never missed a chance to mock what they perceived as the nearly extinct dinosaur of surrealism, with its aging spokesmen no longer so terribly shocking in their studied provocations. In that same period of the ’50s and well beyond, Salvador Dalí’s clownish embrace of magazine advertising, TV, and general media celebrity hastened the impression, in many people’s minds, that surrealism was a spent force, reduced to a bunch of tired clichés—just another ephemeral art-world or showbiz fad.

But there has always been an unbeatable counterargument to any prognosis of surrealism’s demise, and it can be summed up in a name: Spanish-born Luis Buñuel (1900–1983). From his first short, the classic Un chien andalou (1929), to his final feature, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977), Buñuel always stayed true to those primary surrealist principles with which he most identified: a spirit of revolt; the subversive power of passionate love, both romantic and erotic; a belief in the creativity of the unconscious (dreams and fantasies); a pronounced taste for black humor; and, last but never least, an abiding contempt for institutional religion and its representatives.

Indeed, if there is one motif above all others that characterizes Buñuel’s cinema, it is surely the parade (again, from first film to last) of nuns, priests, and even saints, presented as figures who are variously silly, pompous, repressive, and sinister—sometimes all of those attributes at once.

In any decent reckoning with Buñuel, cinema, and surrealism, we must take into account not only his own dazzling career spanning half a century, but also the profound marks it has left on the sensibility of subsequent major filmmakers. Figures including Pedro Almodóvar, Walerian Borowczyk, David Lynch, Věra Chytilová, David Cronenberg, Jan Švankmajer, Sara Driver, Arturo Ripstein, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Jean-Claude Brisseau, and Raúl Ruiz have all absorbed different aspects of the Master and reinterpreted his method in their own fashion.

However, after so many appropriations and recyclings, we may today have a somewhat skewed notion of Buñuel and his art. When we revisit his work, we discover not a torrid, psychedelic, violently disjointed style—the type of thing young art students always imagine surrealism to have been in its anarchic heyday—but the exact opposite: an unnerving calmness, a directness and simplicity in the way he staged the most outrageous situations and spun the most outlandish tales.

“Buñuel meticulously shaped his films as arrows designed to burrow straight into the unconscious of spectators, without undue filters or explanations.”

Un chien andalou

L’âge d’or

Un chien andalou

Viridiana

The Exterminating Angel

The Exterminating Angel

Simon of the Desert

Simon of the Desert

Belle de jour

Belle de jour

Belle de jour

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

The Milky Way

The Milky Way

“Buñuel was a unique mixture of pure artistic intuition and the most skilled filmmaking craft—so skilled that he was able to keep making films well into the 1970s.”