After the musicians had packed up, the fighters stayed on, whether they wanted to or not. Ali’s taunts couldn’t disguise the reality of his endless, grueling workouts—more grueling, many would later say, than Foreman’s. Conventional wisdom held that Ali was risking his reputation and maybe (as Moore worried) his life against Foreman. And some observers perceived spiritual risks too. In When We Were Kings, Plimpton tells a story, deadpan, about how a féticheur, or spiritual healer, had told Ali that Foreman would fall prey to a succubus. (Plimpton says “succubus” twice, and each time the film cuts, rather gratuitously, to footage of Makeba onstage.) Norman Mailer—Plimpton’s friend and rival, who is also featured in the film—is more invested in racial mythology. He describes Foreman as the embodiment of “negritude,” a “huge black force” who becomes, in the ring, “insane with rage.” In 1975, Mailer published The Fight, a book that was ostensibly about this match, although of course it was largely about Mailer. He wrote about himself in the third person, a proud and confused white writer adrift in Zaire. “He no longer knew whether he loved Blacks or secretly disliked them,” Mailer confessed, and both the author and the character seemed to hope that the fight would provide an answer.

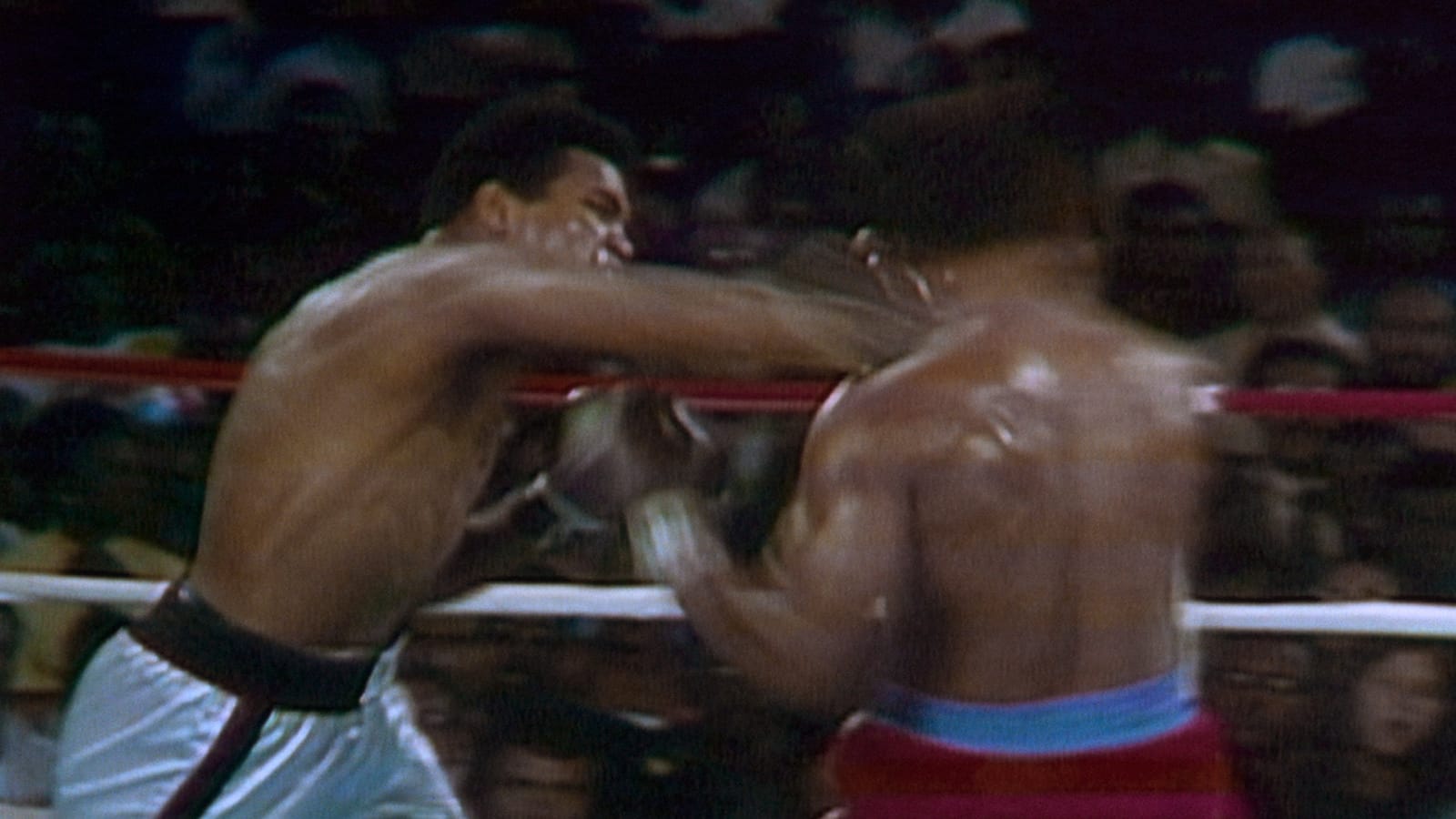

This kind of wild, senseless hope is the reason why boxing is so transfixing: the brutality of the sport makes it seem important and helps convince those of us watching that something important is being decided in the ring. Just about everybody in the stadium was rooting for Ali, and probably most of the hundreds of millions of people watching were too. They must have been horrified by the sight of Ali, listing backward against the ropes, twisting back and forth while deflecting and (sometimes) absorbing Foreman’s punches. This may not have begun as a strategy, but it evolved into one, a way for Ali to let Foreman tire himself out, making him more vulnerable to Ali’s own punches, which were not quite as heavy but heavy enough to eventually end the fight. Like many of Ali’s victories, this one was memorable not because Ali dominated but because he didn’t. We know that he won, but we also know that he suffered.

The excitement of the fight, the charisma of Ali, the bewitching stratagems of King, the stylish energy of the images: all of it combined to make many people see When We Were Kings as a celebration of black culture. Gast, who is white, told the New York Times that at Sundance, where the film had its premiere, one African American viewer had exclaimed, “Never in my life could I have imagined white hands crafting such black pride.” But in Zaire, the cruel “black power” of Mobutu’s presidency lasted for decades; it was only in 1997, around the time that the film arrived in theaters, that the dictator was at last expelled by an alliance of rebels, who brought their own sorrows.

As for Ali, his reward for beating Foreman was the heavyweight championship, and the opportunity or obligation to keep fighting, which he did, more than a dozen more times. In the eighties, as Parkinson’s disease made Ali slower and weaker and quieter, he came to be revered in America as an inspirational figure. By the time he died, in 2016, it was impossible not to wonder what all that fighting had cost him. “He hurt himself,” Mailer says in When We Were Kings, about Ali’s career after the Rumble, but there’s no reason to think he didn’t hurt himself during the Rumble, and probably long before it. When you watch Ali holding court in Zaire, it’s tempting to look for signs that the awful process has already begun—a slight fuzziness in his consonants, perhaps, or a barely perceptible stiffening in the legs that once glided effortlessly around the ring.

Once the fight was over, Foreman grew “depressed beyond recognition,” as he later put it; for years, he claimed that someone might have poisoned him before the match. A few years later, after losing again, to a tough and tricky fighter named Jimmy Young, Foreman saw a vision in his dressing room and became in earnest what Ali had once accused him of being: a Christian. After a decade away, he returned to boxing in 1987, beginning a comeback as unlikely as any in the sport’s history. In 1994, when he was forty-five, Foreman earned another heavyweight championship title—although by that point there were a few different heavyweight champions of the world.The new George Foreman was not a destroyer but a cheerful and charming figure, and he has since been greatly enriched by his decision to endorse a countertop kitchen gadget, the George Foreman Grill. “I was Humbled in the Jungle,” Foreman recently remarked on Twitter. Nowadays, that loss is an important part of his conversion narrative: it helped bring him low so that he could eventually be raised up.

Unlike Ali, and unlike so many of the people who watched the Rumble in the Jungle, Foreman never seemed particularly convinced that the fight meant anything at all. “I don’t think I’m superior to any previous champion,” Foreman told a group of journalists before the match. He said he wasn’t sentimental about his championship: “It’s something I’ve borrowed, and I’ll have to give it up.” This is a sensible perspective, but boxing is not a sensible sport. In fact, on some indelible nights, it hardly seems like a sport at all. When We Were Kings is an enthralling document of this strange alchemical process: it shows us what a great fight can give us—and what it can take away, too.