Swing Time: Heaven Can’t Wait

The problem with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies, everyone agrees, is that there is never enough dancing. You have to wait through often silly plots and hit-or-miss comedy for the musical numbers that are the whole point. But the dances when they do come are so overwhelming and demand such breathless concentration that they must be limited. There is only so much bliss the human system can stand.

Of all the films Astaire and Rogers made together, Swing Time (1936) does the best job of integrating music and dance into a credible story. It also makes us wait the longest to see them dance together. The first number, “Pick Yourself Up,” doesn’t come until thirty minutes in to the movie, making it even more of an explosive relief than usual. Astaire has to drag Rogers unwilling onto the floor, but once they start, it’s like a match thrown onto a pile of gasoline-soaked rags. Fwoom! They dance as though the floor were hot, their taps crackling like oil in a frying pan. Ginger picks up her swirling, pleated black skirt and flashes her fabulous gams. Sometimes, rehearsing and recording these numbers was so grueling that her feet bled, but on-screen she is having the time of her life. “Sheer heaven, my dears, sheer heaven!” Eric Blore cries when they finish. And he was only watching.

All the musical numbers in Swing Time have some element of irony or surprise in their context, as the dance critic Arlene Croce points out in her definitive book on Astaire and Rogers. “Pick Yourself Up” starts with Ginger thinking Fred can’t dance. “A Fine Romance” is based on the equally false premise that he is a cold fish. He serenades her with “The Way You Look Tonight”—which very deservedly won Dorothy Fields and Jerome Kern the Academy Award for best original song—only to look up at the end and see how she really looks, with a towel around her shoulders and shampoo in her hair. (In fact, Rogers is so fetching here that it’s a wonder she didn’t start a fad for wearing a bathing cap covered in whipped cream, as she did to achieve the effect.) Later, he sings “Never Gonna Dance” and promptly starts dancing. The film is a “jazz rhapsody,” Croce writes, whose “materials are romantic irony, contrast, the fantasy of things going in reverse.”

“The dynamic in their dancing is that of their whole relationship: first a clash and then a fusion between her down-to-earth realism and his antigravity romanticism.”

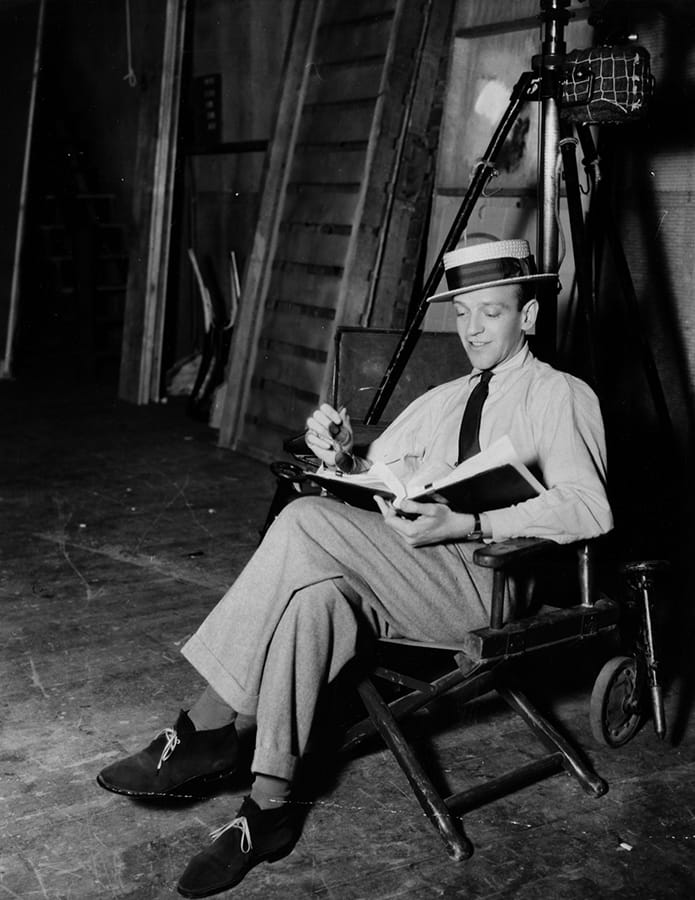

George Stevens and Fred Astaire

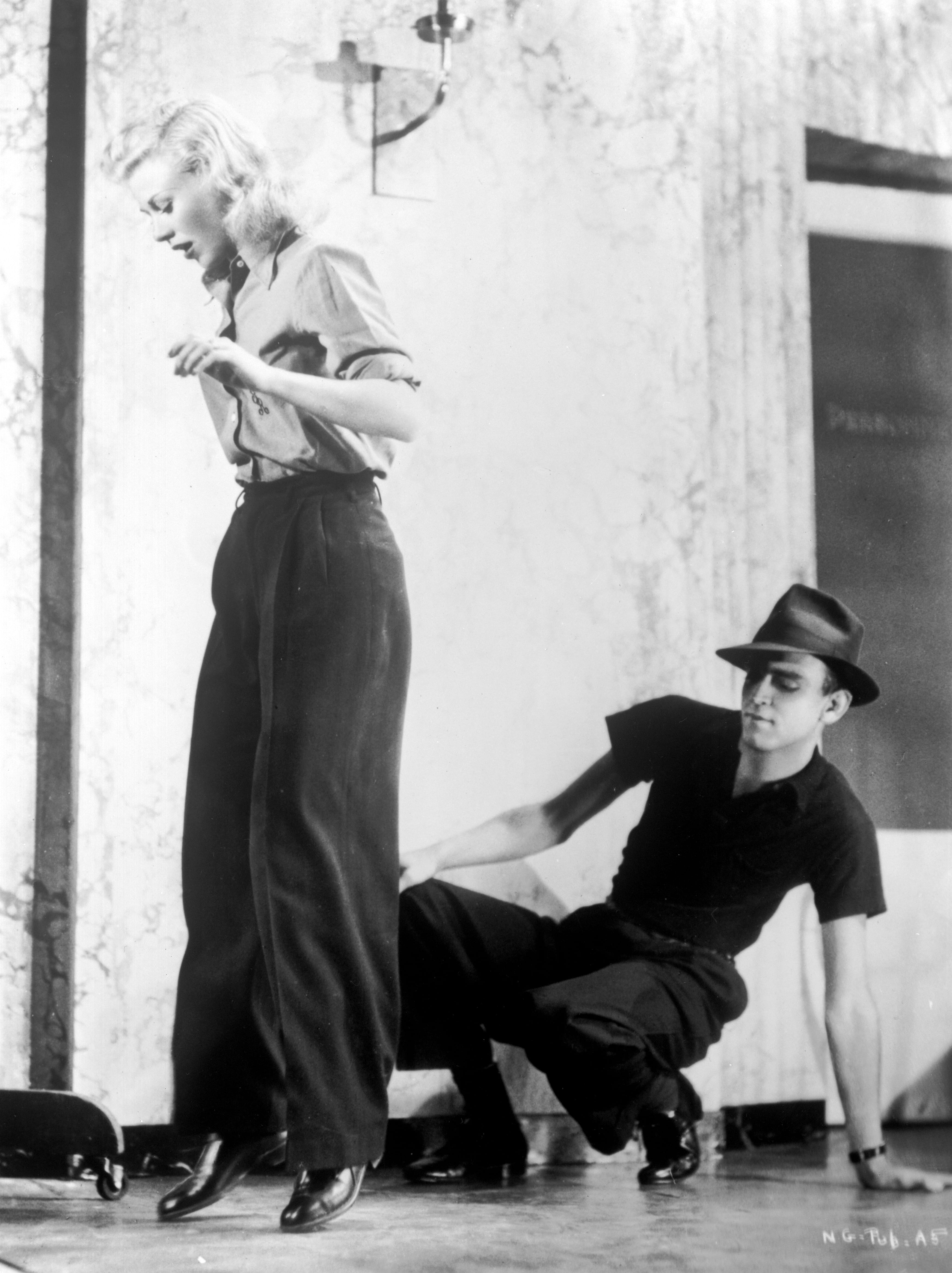

Ginger Rogers and Hermes Pan

Astaire

Rogers and Pan

Astaire, Rogers, and Stevens

“Astaire and Rogers exhaust superlatives, yet after you get tired of praising them, there is ‘Never Gonna Dance,’ their masterpiece.”