Pitfall: Outdoor Miner

Pitfall is the kind of semiuncanny, equivocally realist movie you might hope to duck into in a strange city, stumbling across it in a low-rent theater while escaping a bad date or a debt collector. Impressively anomalous and consistently unpredictable, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s 1962 first feature manifests a literally fugitive quality. Opening in restless midstride, with a desperate miner fleeing with his small son down a dark alley, skipping out on a slave-labor existence, it proceeds to gravely leapfrog from one narrative strand to the next, with an unfussy disregard for the linear. Living on the cheap and off the grid, Pitfall’s sparse array of nervous, wobbly humans are stalked by a universe they scarcely apprehend, let alone comprehend, all fast on their way to becoming phantoms.

Mining supplies the film’s hellish governing metaphor, such as it is. But misdirection and misunderstanding are Teshigahara’s specialties here: straggling people bombarded with confusion, developing an especially persuasive and exacting strain of displacement in the process. From the doomed man (Hisashi Igawa) and his pint-size boy (Kazuo Miyahara, a staring tyke with the ornamental qualities of a bad-luck charm) to a tame, candy-vending doxy in an abandoned mine camp, these figures are newsprint cutouts strung from the end of civilization’s rope. They have no place to go but down: fifteen minutes into the movie and our running man has humiliatingly signed on at another mine, with impoverished circumstance serving as a conveyor belt taking him straight to his imminent demise.

A cult movie lacking only a cult, Pitfall leaves potential audience hooks (murder, conspiracy, quizzical ghosts, poetic disquietude, a cosmic agent provocateur) dangling in midthought, slicing identification off at the knees. Next to his ultracomposed, finely sifted masterpiece Woman in the Dunes (1964) and the modishly Gothic horror-as-everyday-life of The Face of Another (1966), this film is a disconcerting blend of visual acuity and pointedly unpolished effects, relentlessly shambling between sophisticated and primitive setups, integrating unlikely elements in a completely self-contained/-referential enclosure. Yet its contractions never feel like a neophyte’s cinematic pastiche. Teshigahara notoriously called it a “documentary-fantasy,” which is a rare case of such a loaded term actually being precisely applicable: he treats the fantastic and the “nightmarish” with a mulish, mundane objectivity.

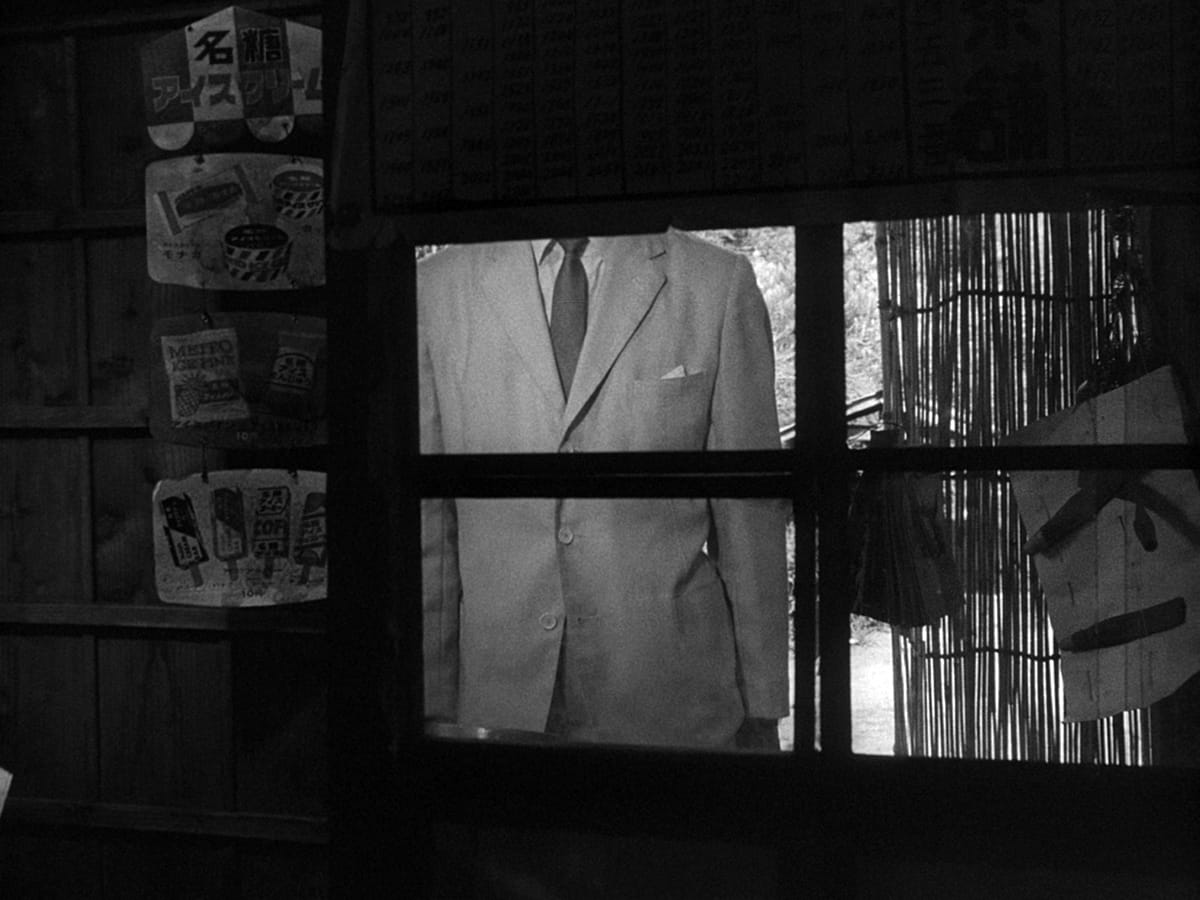

There is a truly alien quality to this film—not so much plain garden-variety foreignness as the remorseless (il)logic of an unfamiliar and unimpressed intelligence casting prismatic insect eyes on the human condition. Peering at the workaday peasant countryside and its lumpish, useless, jaundiced creatures, the lens looks on with the magnifying-glass impassivity of an ethnoentomologist examining a mutant species of two-legged centipedes. Out of nowhere, a man in a white suit follows, photographs, and soon knifes the nominal protagonist, the bird-watcher turned assassin, or possibly shadow auteur, orchestrating the plot against the poor schmuck as part of an obscure scheme to implicate the miner’s union-leader double. (Did I mention that Igawa plays both the miner and his doppelgänger, not to mention the murdered miner as long-faced ghost?)

Treating the supernatural as dull and commonplace (the dead talk in a stream of morose why-me self-pity, but the living refuse to see or hear a thing), Pitfall is an anti–ghost story atop the slippery slope of a faintly deranged slide show, an intellectual Carnival of Souls cunningly blurring distinctions with an evenhanded, cryptic bluntness. Thus for an American viewer of a certain age or disposition, Pitfall’s symbolic tendrils will recall not only the unyielding, reappraising gazes of Imamura and Oshima, and the contemporaneous alienation ’n’ angst heyday of the Bergman-Resnais-Antonioni bunch, but also the lurching, wayward tangents of Ed Wood and Russ Meyer (think of a Mudhoney sans the honeys), plopped down among the neurotic-ironic black-and-white TV allegories of Rod Serling’s Twilight Zone. Less a discrete boxed-up narrative than an interlaced set of abstract convolutions, Pitfall suggests a sort of crabby, scrambling cinematic anagram. Or a bargain-basement cultural fallout shelter stocked with canned existential goods, dehydrated insignificance, and doleful social dartboards, all treated with a bracing lack of concern or respect.

Every few minutes, Pitfall seems to morph into or back out of a new movie—shades of underclass struggle (abrupt newsreel inserts of starving, deformed children and striking miners, the occasional sharp note of leftist requiem), hearty folk con game (a couple of scamming miners scrounging food by pretending to dig for coal on the hopeless property of an “old hick” farmer), modernist paranoia (cool Mr. White Suit lurking in the telephoto distance, then slipping into close-up range for the kill), haunted tract housing (an actual ghost town), or the whole broad-daylight netherworld that encompasses them all. In its intently compacted landfill of a mise-en-scène, Pitfall nicely avoids any easy, rational categorization as foregone tragedy or even brackish bombed-out absurdism. “Being invisible might have been useful when I was alive,” the miner’s thick specter moans obliviously, “but this is unbearable.”

The little kid sees his father killed, examines the body, and removes a candy bar, but remains as stone-faced as a miniaturized Buster Keaton, weaving his curiously prepossessed way through the film like a loose kite, eventually racing off down an empty road in the picture’s enigmatic closing shot. The candy woman (Sumie Sasaki) has a dumpy shopkeeper attractiveness, waiting in stifling heat for the mailman (in a ghost town?) to bring a letter from the long-gone boyfriend—or john—she insists will still send for her. Swatting flies and slumping to the floor like a sack of flour, she is too weak to offer much resistance to anything that comes her way. Witnessing the miner’s murder from her window, she is bribed by White Suit into fingering the head of a union faction—the rival of the dead man’s look-alike. Falsely reporting the crime, in no time she’s raped by a lecherous policeman, an act given such an incredibly humdrum, squirming, hapless quality it seems perpetrated out of nothing more than malignant boredom, consumed with total futility. Cutting away in midviolation, the movie drops in a whole sheaf of subplot exposition, only to return to the scene to find it still in progress. And then (Pitfall is nothing if not a series of insult- and injury-laden “and then” curses visited upon its wretched inhabitants), her usefulness expended, White Suit immediately returns to kill her, and takes back his money.

The dog-eat-dog perspective of so much modernist Japanese cinema is apparent here, yet Teshigahara imbues it with a provisional, uninflected tone. Even when the gleaming, canvas-splattering dissonances of ace composer Toru Takemitsu’s score burst through the drab silence like percussive monkeys rattling their John Cages, there is an improbably accepting air hanging over the picture. Panning across a strip-mined landscape to menacing noises from deep in the gut of an amplified prepared piano, Teshigahara somehow manages to achieve a bizarre pastoral effect—like a contemplative snippet from a concerto for drill bits and copper wire, where image momentarily becomes wholly secondary to sound. Although he was working from a screenplay by novelist Kobo Abe, an early collaborator and guiding spirit, it feels as though the movie is constantly seeking to escape any literary origins, or shake free of the very postwar avant-garde reference points it is strewn with. Pitfall uses flattened, nondescript settings and dollops of visual banality to reinforce a sense of impoverishment, squalid nothingness, creating a discontinuous physical world where a huge mining operation and an abandoned camp seem miles apart one minute and a stone’s throw away the next, with geographic and spatial relationships as much in doubt as their human counterparts.

So while Teshigahara came to film out of such exacting traditional disciplines as flower arranging, painting, and sculpture, Pitfall regularly injects notes of deliberate, productive amateurism to keep things on edge. This isn’t to imply any degree of carelessness or incompetence but rather to indicate that the shots maintain an opportunistic, hunt-and-peck element that keeps the film rooted in grubby transience, depleted nature. The compositions don’t have that finished, richly lacquered symmetry that is typically wheeled out to signify artistic meaning and worth; only a too-neat glimpse of a sinking “Unity” armband is ostentatious. (Even the fidgety inserts of feet and hands have a much more off-the-cuff quality than Bresson’s Calvinist woodcuts.) A long take of cloud shadows passing over a mountainside has the eerie, cast-off aura of an old postcard—and so do the beads of sweat, empty masks, tumbledown living quarters, and all the other loose trinkets of Teshigahara’s modest, homey limbo.

Likewise, the acting is purposefully functional, without much trace of either mannerism or woodenness. As with ghosts doing posthumous exercises and rituals, they go through the motions with a heedless efficiency. When the phantom miner knocks on the woman’s door, she answers: “I’m home all right, but I’m dead.” Join the club seems to be Pitfall’s refrain. He wants answers, but no one alive or dead seems to know anything, except for the killer, who appears to occupy his own private conspiratorial universe to which no one else has access: by setting the New Pit faction against the Old Pit, the film’s handy deus ex machina begins a chain reaction of betrayal, distrust, and fatal misunderstanding. Which is par for the course on the Pitfall links: the postman finally shows up with the dead woman’s letter (“I’ll never know what it says”), the miner’s doppelgänger tries to warn his rival of the frame but gets accused of the woman’s murder himself. He winds up drowning his framed accuser, before collapsing in the mud, while the boy watches from the bushes. The ghosts plead for an explanation but none is forthcoming.

“Exactly as planned,” pronounces a satisfied White Suit, before tootling off on his motorbike. Every one of these lemmings contracts exactly the wrong idea, just as planned, and ends up in the selfsame hole. Only the kid is still left alive, stocking up on candy and shedding a quick humanoid tear, before sprinting through the ghost town (the camera keeping up with him from the other side of the camp) and out of sight, as fast as his spindly legs will carry him.