Midnight Cowboy: On the Fringe

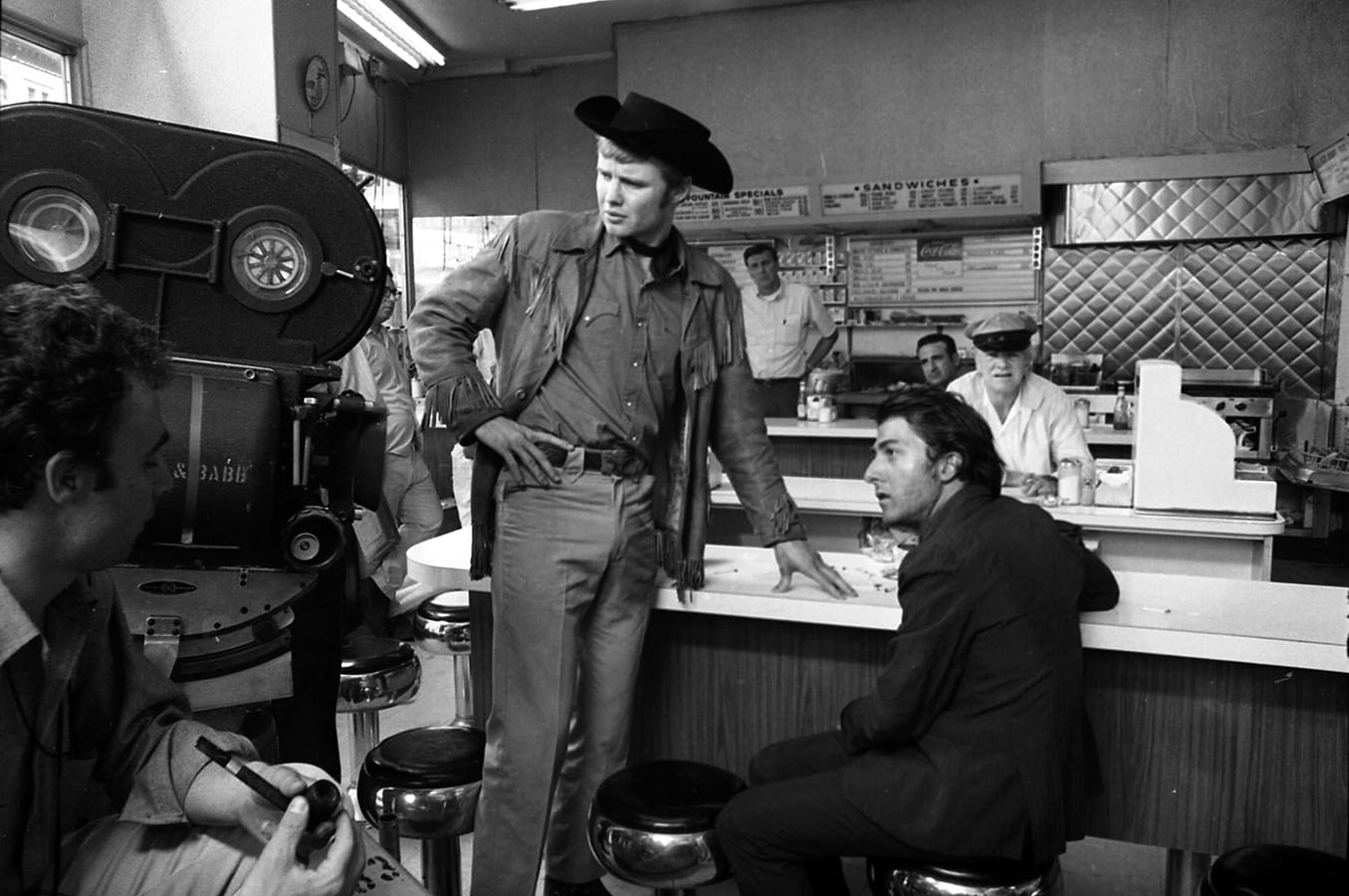

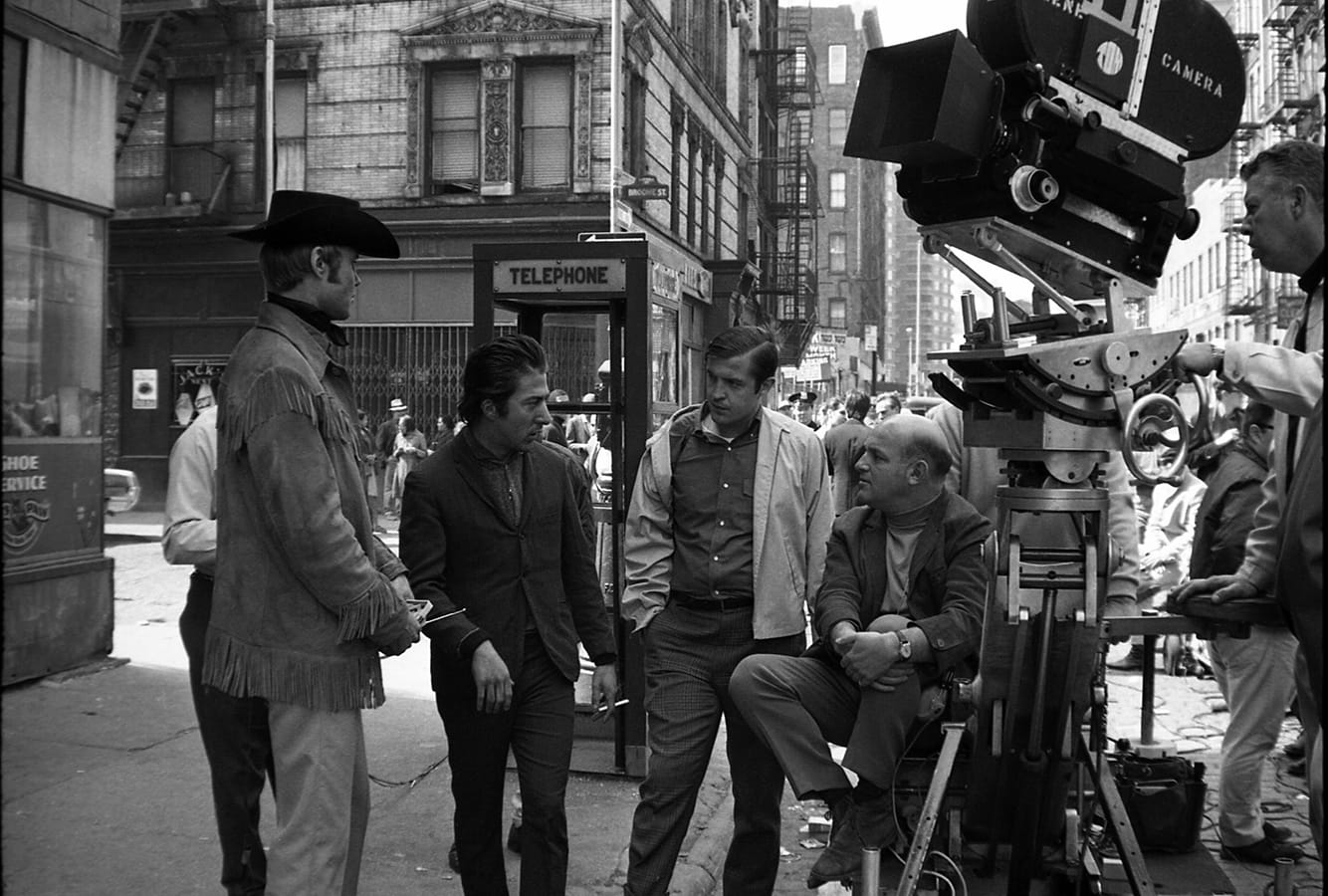

John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy is a milestone along several different paths of movie history, all of which converged at the majestically seedy crossroads of Times Square in the spring of 1968, when it was filmed. As a New York movie, as a barrier breaker in terms of adult content, as a representation of a new, more daring Hollywood, as a buddy film, and most complexly as, if not a gay movie, a movie that at least helped to make the notion of a gay movie possible, the film represents a true dividing line, albeit not one that everybody immediately recognized. “Having seen it,” wrote New York Times critic Vincent Canby when it opened, “you won’t ever again feel detached as you walk down West Forty-Second Street, avoiding the eyes of the drifters, stepping around the little islands of hustlers.” But, he concluded, “it’s not a movie for the ages.” Ironically, it’s the Forty-Second Street about which Canby wrote that is long gone, its porn palaces, pawnshops, and fleabag hotels driven out by a massive urban/corporate rebranding. But people still come to New York with unfulfillable hopes and end up living on or over the edge of desperation, and Midnight Cowboy, one of the first movies to find them, has endured.

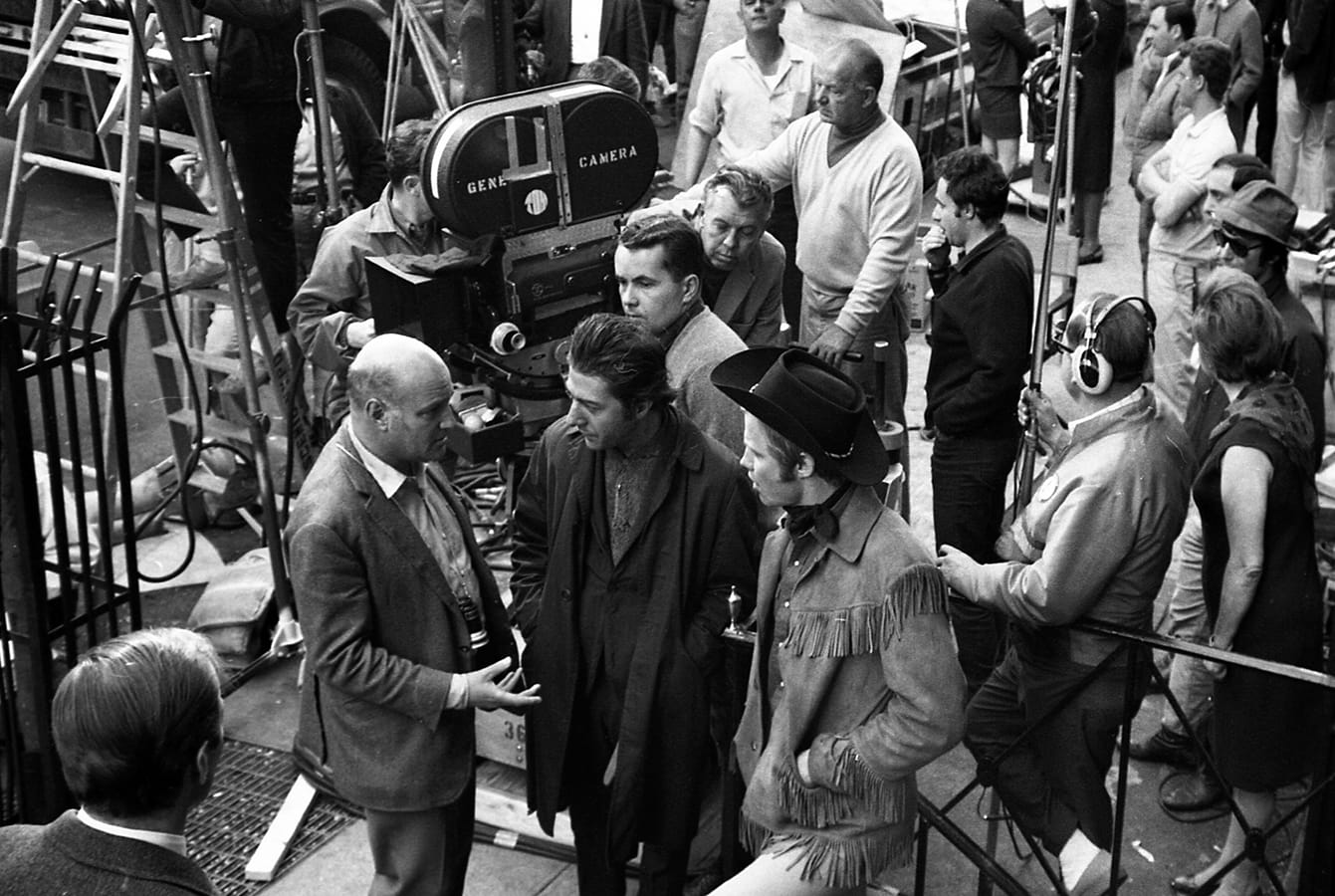

It took someone on the fringe to make it, and to make it work so well. The London-born Schlesinger was gay and Jewish—a double outsider in his home city, and as a gay Englishman, a double outsider when he came to New York. Schlesinger was already on the map because of his 1965 hit Darling, a stinging portrayal of swinging London’s brittle, heedless smart set that had won Julie Christie an Academy Award and gotten Schlesinger his first Oscar nomination. He was eager to make a picture in the United States, and shortly after Darling, he seized on James Leo Herlihy’s 1965 novel about the guileless hustler Joe Buck and his only friend, Enrico Salvatore “Ratso” Rizzo, and brought it to producer Jerome Hellman and United Artists.