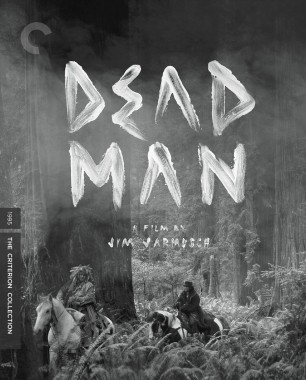

Dead Man: Blake in America

Films don’t change in themselves over time, but the passage of time almost always affects what we make of them. Not so Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995), which confronts us with images of startling beauty combined with actions of devastating cruelty whose emotional power and mystery have not diminished in the decades since its release. What do we mean when we say a narrative film is poetic? The answer is Dead Man.

A visionary, rather than revisionist, western, Dead Man describes the journey of two outsiders, William Blake (Johnny Depp) and Nobody (Gary Farmer), from the town of Machine, a mid-nineteenth-century frontier outpost of the Industrial Revolution, to the Pacific Northwest. Blake has blown his savings on a railroad ticket from his hometown of Cleveland to Machine, where he believes a job as an accountant for Dickinson Metalworks awaits him. No such luck. Someone else has gotten there first, and after Blake is mocked by the desiccated office manager (John Hurt) and his Kafkaesque staff, and threatened by Dickinson (Robert Mitchum), a self-aggrandizing titan of industry who has hung a life-size portrait of himself behind his desk, he’s out on Machine’s mean streets. There, starving inhabitants scavenge for food and demand blow jobs at gunpoint in alleys lined with the skeletons and skulls of all kinds of animals, including humans. Blake winds up in the bed of a jaded paper-flower seller, only to watch helplessly as her jealous boyfriend puts a single bullet through them both. She dies instantly, but Blake, though badly wounded, picks up the gun they’ve been playing with and, to his surprise, kills the boyfriend with the third shot. Mortally wounded, he escapes the house through an open window. A door might have been easier, but Blake is no longer making rational decisions, if he ever has.

There are several ways to read the narrative that evolves from this setup. One is that all of it is Blake’s dying vision. Another is that he has already died and is journeying through something like the bardo or purgatory. And still another is that Nobody, an outcast because his mother and father were from different tribes—Piikani (Blackfoot) and Apsáalooke (Crow)—finds Blake in the wilderness and decides it is his mission to teach this “stupid fucking white man” how to “pass back through the mirror” by taking him on a trip across physical as well as metaphysical realms. It’s irrelevant which interpretation you prefer. Each has its own logic. What all of them point to is mortality as the preeminent existential condition of our lives. Nobody is baffled that Blake doesn’t know of his namesake, the English poet, or his work, which encourages us to acknowledge our death so that we can live fully in the present moment. Nobody encourages this in his William Blake, just as Dead Man does in the viewer.

It is Jarmusch’s investigation of the formal and expressive relationships between poetry and movies that makes Dead Man such a rich work. In that, Dead Man stands apart from the dark, revisionist westerns to which it is often compared: everything from Robert Aldrich’s Ulzana’s Raid to Robert Benton’s Bad Company (both from 1972). An anomaly among Jarmusch’s films as well, it is the only one with a noncontemporary setting. While in Only Lovers Left Alive (2013) Jarmusch presents history as the living memory of the undead, in Dead Man history becomes prophecy. When progress is defined by capitalism, the result is the pillaging and blighting of the natural world and its inhabitants, as the poet Blake foresaw at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Like Dead Man’s William Blake, Jarmusch was born in Ohio, a state that boomed and cratered with the economy of steel and heavy manufacturing. Where the fictional Blake went west, Jarmusch went east, to New York, where he studied English literature at Columbia University and was encouraged to write poetry by two of his teachers, the poets Kenneth Koch and David Shapiro. After a year in Paris, where he fell in love with cinema, he returned to New York, enrolled in NYU’s graduate film school, and made his first feature, the promising but amorphous Permanent Vacation (1980). With Stranger Than Paradise (1984), he defined the elements of his cinematic style, particularly the deadpan humor, elliptical editing, and deliberate framing, which made the film so different from the unexamined realism that prevailed in American independent films of the eighties. Although Dead Man was Jarmusch’s sixth feature, it has more in common with Stranger Than Paradise than with any of the three intervening films, Down by Law (1986), Mystery Train (1989), and Night on Earth (1991). Like Stranger, it depicts the existential loneliness of individuals, alienated from an incomprehensibly vast landscape. Commonly categorized as a New York movie, Stranger Than Paradise opens on Manhattan’s Lower East Side but then moves to the Midwest before ending in Florida. But like William Blake, wherever its characters go, they are fish out of water. The nearly whited-out image of a frozen lake in the middle of a blizzard seems like a preview of the dense forests and empty clearings of Dead Man, in which William Blake would be lost if he didn’t have Nobody as a guide. And like Stranger, Dead Man is filmed in black and white, with each sequence separated by blackouts, as if they were verses of a poem or songs on an album, and almost every blackout is rhythmically marked by one of Neil Young’s ominous electric-guitar riffs.

In numerous interviews, Jarmusch has explained that while he was writing Dead Man, he took a break from studying Native American texts to reread Blake, whose mysticism had been embraced by the American Beat artists and writers who were strong influences on him. An immensely prolific writer, Blake was also a printer by trade. By owning the means of reproduction, he was able to publish his own work whenever he wanted. While Jarmusch is not similarly prolific, he, too, has preserved his independence through ownership, by retaining the negatives of his films. (In this, he is almost unique among contemporary American narrative filmmakers.)

In the case of Dead Man, Jarmusch was able to prevent Miramax, which acquired distribution rights to the film after it was finished, from forcing him to reedit. Miramax’s Harvey Weinstein, then known by what now seems like the relatively benign nickname of Harvey Scissorhands, was so infuriated by Jarmusch’s refusal that he sabotaged the release by severely restricting press screenings and refusing to support the film for awards. Nevertheless, by the end of the nineties, Dead Man had emerged as one of the most lauded American films of the decade.