Mafioso: Meet the Badalamentis!

The 1960s were a heady time for Italian cinema. On the one hand, you had the postwar art-house powerhouses—Rossellini, De Sica, Visconti, Fellini, and Antonioni—all operating in full gear, with a younger crop (Pasolini, Zurlini, and Scola) bringing up the rear. On the other hand, you had an imitable strand of popular, cynical Italian comedy, by such polished directors as Alberto Lattuada, Pietro Germi, Mario Monicelli, and Dino Risi. The auteurs versus the craftsmen, you might oversimplify the situation by saying. In retrospect, however, commercial comedies such as Germi’s Divorce Italian Style, Lattuada’s Mafioso, Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street, and Risi’s Il sorpasso have come to be regarded as cinematic masterworks in their own right, every bit as complex and personal as those by the art-house auteurists.

Lattuada is an especially interesting case. Brought up by his father, the composer Felice Lattuada, in an opera-drenched atmosphere, he trained as an architect, but was movie mad and helped start Italy’s first film archive. He began his directorial career by making literary adaptations in the “calligraphist” manner—the Italian equivalent of what the French new wave disdainfully called “the cinema of quality”—partly to evade the Fascist censors. After Italy was liberated by the Allies, Lattuada called for a neorealist cinema: “We are in rags? Then let us show everybody our rags,” he wrote. He directed neorealist melodramas such as The Bandit and Without Pity, but his first real masterpiece was undoubtedly Variety Lights (1950). This bittersweet comedy about a troupe of traveling players—often erroneously attributed to Fellini, who wrote the script and is credited alongside Lattuada as codirector—was actually a full-fledged demonstration of Lattuada’s flair for exposing the weakness of masculine vanity and the strength of female opportunism. It also demonstrated what Lattuada himself called his main theme: the isolation of the individual, attempting to pursue a glimmer of happiness, in the face of society’s opposing pressures to conform.

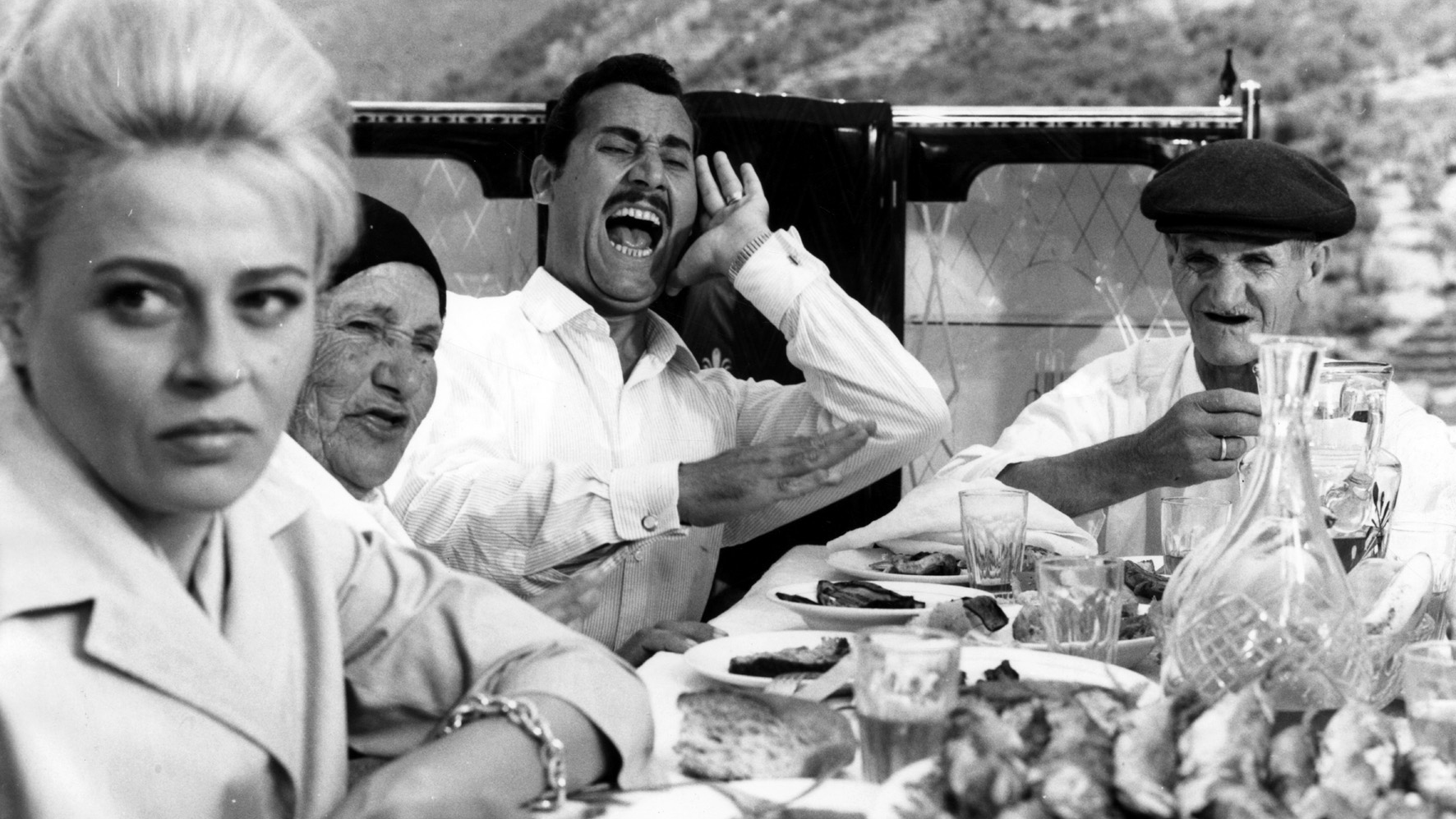

Lattuada’s supremely hard-nosed comedy Mafioso, which won the grand prize at San Sebastián in 1963, further elaborated on this theme of the individual versus the group. The plot centers on Nino Badalamenti, a go-getter foreman in a Milanese car factory. Though he grew up in Sicily, Nino has, for all intents and purposes, become a northerner, pacing the factory floor with stopwatch in hand, hawkeyed against malingerers, thinking himself shrewd, nobody’s fool. Now he is taking his wife and two daughters on vacation back to his native Sicily. It is the first time his slim, sophisticated, blonde wife will be meeting her husband’s family; and Nino, who has been away from his homeland for years, tries to counter her trepidation and lack of enthusiasm by singing the praises of Sicily as a joyous place filled with scented oranges. What they encounter is instead a dour, suspicious populace, wily, cretinous, upholding a bloody code of honor. Nino’s wife offends the traditionalists by lighting up a cigarette, and by bringing gloves to her father-in-law, who, unbeknownst to her, has lost a hand through gunplay. Half the townsmen are unemployed lechers, the other half work for the Mafia.

The film can be seen as a parable of regional/class tensions: between the go-getter, optimistic, modern northern Italy of the economic “miracle” and the poor, backward, pessimistic south, still ruled by bandits and gangsters, embodying a corrupt past that has never gone away. Nino tries to bridge these two worlds with an increasingly desperate bonhomie and gregarious flattery; but no one is fooled, especially not the old Mafia chieftain, Don Vincenzo, who calls in a favor and enlists Nino as a hit man. Nino thus enters a world where even glib words (he had promised to do anything the old man requested) have consequences. In its pre-Godfather, anti-nostalgic, decidedly unromantic treatment of the Mafia, Mafioso uses the criminal-society plot to impose implacability on an otherwise random, frivolous world. Without this engine of fate, we would have had merely a stock, if amusing, comedy about culture clash, such as Meet the Parents; with it, the stakes and the danger keep being raised. Like Divorce Italian Style, this is one grim comedy that does not flinch at murder.

No one could better embody the “average Italian” in all his swagger, cowardice, hypocritical geniality, and reluctant nobility than Alberto Sordi; and Nino is undoubtedly one of his greatest performances. Known to his fans and detractors as the Emperor, Sordi was almost handsome enough to be a matinee idol, had not a certain pudginess of cheek and largesse of nose gotten in the way. Sordi’s character here is essentially that of a conceited boy who has never grown up; his vanity prevents him from understanding the iron forces arrayed against him. Yet we can’t help liking him, partly because, as the actor himself put it, “impulsiveness and vitality are part of my character,” and partly because Nino takes such tender, touching pride in his little family. He is certainly not a macho, even correcting one of the Sicilian toughs: “Doing what your wife wants isn’t a sign of weakness.” (Norma Bengell, the non-Italian actress who plays his wife, brings an endearingly convincing air of baffled estrangement to the proceedings.) Yet even here, Nino’s city-dude smugness undermines his enlightened feminist message, so you’re not sure whether to applaud him or laugh at him.

One peculiarity of this golden age of Italian screen comedy was that, while it grew out of neorealism and never abandoned grubby locations or gritty social facts, it nevertheless drew the opposite emotional conclusions by substituting mockery for pity. In fact, it can be argued that the best Italian comedies elicited a deeper sympathy than, say, the manipulated-naive bathos of “tragic” films like La strada, by showing their protagonists’ craven flaws and yet still regarding them with affection.

Mafioso is filled with delicious touches, such as the discussion about alienation by several Sicilian beach bums, the alarmingly abundant welcome-home feast, or the dilemma around Nino’s unmarried sister’s mustache. Comedy is perhaps more reliant on good screenwriters than any other genre. The bedrock of Italian film comedy of this era was its terrific corps of veteran dialogue writers; and this film boasted not only the great Age and Scarpelli (Agenore Incrocci and Furio Scarpelli)—the most famous screenwriting team in Italian film history, responsible for many of that nation’s best comedies and dramas, including Seduced and Abandoned, La grande guerra, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly—but also Marco Ferreri (who directed his own comedies, such as The Ape Woman and La grande bouffe) and Rafael Azcona. Together they imparted an uncharacteristically ferocious satiric edge to Lattuada’s smooth, agile penchant for the comedy of vanity.

When we have subtracted the contributions of great comic acting, brilliant scriptwriting, a splendid score by Piero Piccioni, what is still left to characterize Lattuada’s direction? One word: vivacity. He keeps the action moving by any means necessary: sometimes tracking, sometimes employing enormous close-ups, or cutaways to the landscape, zooms, stylized lighting. In short, he eschews any austere signature style, but draws eclectically and pragmatically on every technique available and melds them into a vibrant, yet calmly proportioned, whole. As Edgardo Cozarinsky, the film critic–director, wrote admiringly, Lattuada’s “eclecticism has obstructed an evaluation of his unusual achievement . . . The capacity to work with given materials and achieve something else, in quality and tone, has been one of Lattuada’s elusive talents . . . [and his films] often prove more biting, more complex than the flashy concoctions of most ‘new’ Italian directors.”

The alluring aesthetic of sixties widescreen black and white has never looked better: Lattuada uses it both for a fluid mise-en-scène that embeds his characters in detailed social environments and for expressionistic effect, as when he floods the screen with noirish shadows in the night sequence before Nino’s departure. (Warning: if you have not watched the film yet, you should do so before reading further!)

The most startling stylistic tour de force occurs when the film suddenly shifts location to New York City. We move from the horizontal, parched landscape of Sicily to New York’s vertical cityscape (Nino plays tourist, craning his neck at the skyscrapers, to distract himself from the murderous task ahead), and from the operatic intensity of Verdian verismo to the deadpan, sunlit, semidocumentary cinematography of Don Siegel’s The Killers or Irving Lerner’s Murder by Contract. The scene in the barbershop is both outrageously climactic and strangely matter-of-fact, illustrating that “we are all murderers,” or could be, given the appropriate circumstances.

Mafioso, this ostensibly diverting entertainment, takes us to a horror-film conclusion where Nino is left quivering with terror—at himself and the way the world operates. Yet by shuttling Nino between the dehumanizing, regimented factory at both ends of the film and the vulpine Mafia in the middle, Lattuada suggests a rough equivalency between the two systems. They are both part of the same ruthless, every-man-for-himself continuum. Lest the film be thought of as historically bound to some quaint period in the past, we are reminded that recent statistics show organized crime still occupies the largest sector of the Italian economy. If anything, in its portrayal of the long international arm of the crime families, Mafioso offers a prescient look at globalization. All you can do, faced with such innovating and enduring corruption, is sigh, or laugh, both of which Lattuada’s ingenious comedy teaches us to do.