Antonio Gaudí: Border Crossings

During the Second World War, when Hiroshi Teshigahara was a schoolboy, Japan’s cities—above all his hometown, Tokyo—were mercilessly firebombed. He, and his future associates in countless artistic undertakings, returned to a landscape of bleak ruins. The adolescent Hiroshi was particularly attuned to his environment. His father, Sofu, was the iemoto, or “master,” of an international chain of ikebana (flower arranging) schools and was also an avant-garde artist to whom aspects of landscape were of signal importance. While growing up, Hiroshi had been exposed to art books, paintings, and the conversation of artistic visitors from all over the world. These encounters prepared him for an inevitable education as an artist after the war. In art school, he developed his skills as a draftsman and painter, laying the groundwork for his future activities as a multidiscipline artist.

His generation was charged with building a way to exist in the desperate circumstances they had inherited. Myriad groups formed and dissolved, dedicated to passionate discussion and sometimes group demonstrations. Hiroshi was in the thick of it, listening, expounding, and living a bohemian life. Prominent survivors of the prewar avant-garde, who had spent their youth in Paris, exhorted young artists to build a totally new culture, expunging all memory of the militaristic milieu of their childhood. Hiroshi listened. He heard, and never forgot, the message of Taro Okamoto: extreme contrasts, “violently dissonant” relations, conflict and opposites, must be held in balance. Okamoto also spoke of what he called “total art,” and was largely responsible for the pronounced tendency of Hiroshi and his friends toward a union of all genres—a modern adaptation of Richard Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk.

In 1959, Sofu Teshigahara embarked on a journey to Europe and the United States, bringing with him an entourage of assistants that included his son, Hiroshi. For the younger Teshigahara—who had restlessly explored painting, printmaking, sculpture, and, in a rudimentary way, the one art form his father had never engaged with, filmmaking—this voyage was to be a defining moment in his life. A sojourn in New York, where he discovered a wholly different avant-garde that spent little time in endless aesthetic and political discussions, liberated him and also provided him with experiences he could never have had in Tokyo, such as the discovery of the American boxer José Torres, who would later be the subject of one of his early experimental films.

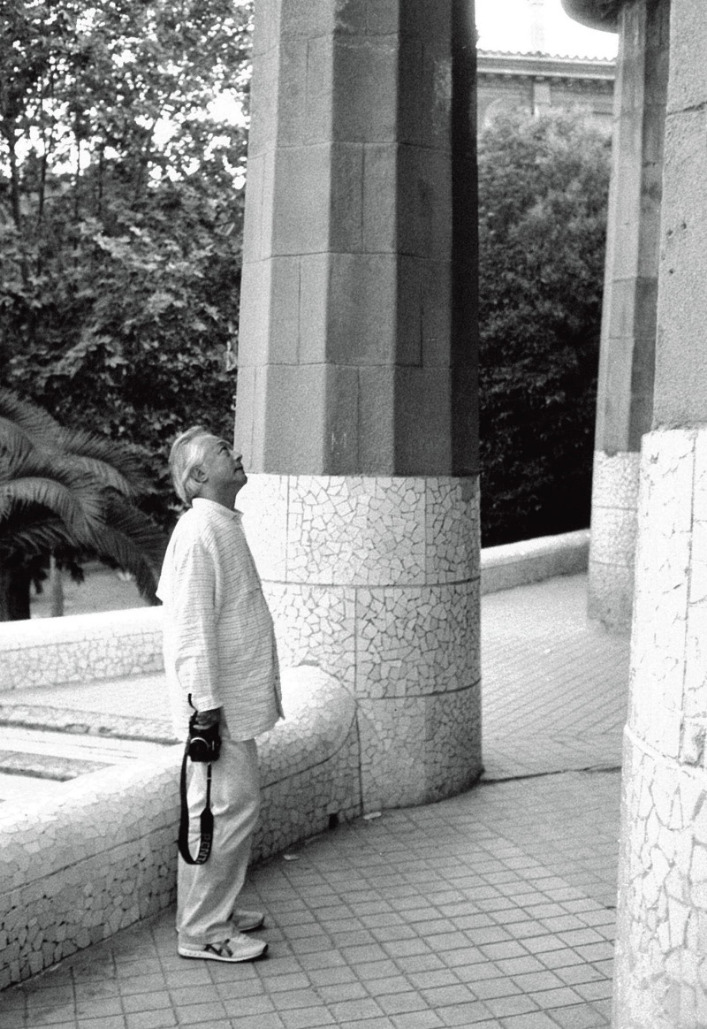

But as exhilarating as his experience in New York was, it was in Spain, as he often recalled after, that he found his artistic way forward and formed a definite approach to what the Tokyo vanguard called “cross-genre” art—the result, in large part, of his encounters with the works of Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí (full name in Catalan, Antoni Gaudí i Cornet; in Spanish, Antonio Gaudí y Cornet). In Barcelona, he said, he came “face-to-face with Gaudí,” and “the magic of it overwhelmed me.” He carefully studied the Casa Milà (La Pedrera), eventually with his 16 mm camera in hand, and then visited every Gaudí site with intense attention. Gaudí’s structures, he later said, “made me realize that the lines between the arts are insignificant. Gaudí worked beyond the borders of various arts and made me feel that the world in which I was living still left a great many possibilities.”

He would explore those possibilities extensively on his return to Japan. Not only did he intensify his earlier interest in film, particularly European films—including those of the Italian neorealists, the French experimentalists, and especially Luis Buñuel—but he began editing his own footage of both José Torres and Gaudí’s architecture. He also took over the auditorium of his father’s Sogetsu school, where, as impresario, he established a film series and hosted performances by such stellar international artists as John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Merce Cunningham, and Yoko Ono, as well as early butoh theater events. He saw his responsibility as an educational one. Having been distracted in his own youth by political questions and debates, and ideas of “revolution,” he meant to impress upon the next generation the importance of artistic life on its own terms. In the course of his hectic managerial life, he himself was drawn ever more certainly into a condition of being a total-work-of-art worker—something that greatly broadened his views when he became a feature filmmaker.

The Sogetsu events gave Hiroshi the opportunity to bring together in collaboration the artistic contemporaries of his college days who had by the 1960s defined themselves as internationalists. Two of those artists, novelist Kobo Abe and composer Toru Takemitsu, would become close associates of Teshigahara’s when he began his career as a filmmaker. Abe, who had been a strong intellectual influence when Teshigahara was a young political activist, participated at Sogetsu in various capacities and would become Teshigahara’s screenwriter on several notable films, including Woman in the Dunes (1964), the screen version of his own novel. But, as with many of Teshigahara’s collaborators, Abe was a direct participant at every stage. He accompanied Teshigahara when he scouted for locations; he was often present at shooting sessions, and his suggestions for individual shots or long perspectives or special light effects were honored by Teshigahara. The same was true for Takemitsu, who produced the music and sound effects for nearly all of Teshigahara’s films. Takemitsu would be on location making notes, and often sat in on the editing sessions. His own commitment to cross-genre art made him unusually sensitive to Teshigahara’s vision, which the filmmaker described as “a collision of sound and image.”

It was during the sixties that Teshigahara began forming a definite position concerning the nature of documentary film. His first effort at presenting the work of another artist had been a matter of trial and error, since he had had no training. While he was struggling with what became Hokusai (1953)—a detailed study of the Japanese draftsman and woodblock master who had called himself “the old man in love with drawing”—he met the seasoned documentary filmmaker Fumio Kamei, who took him on as an assistant. Teshigahara worked on three of Kamei’s documentaries, each of which was an indictment of social and political situations in Japan from what Teshigahara called “a leftist point of view.” It was the ideological bent that Teshigahara began to question: “Kamei was perhaps too concerned with conveying his feelings,” he recalled. “Eventually he bypassed contradictions, bypassed brutal truths, the darker side of issues where contradictions occur.”