The 400 Blows: Close to Home

François Truffaut’s first feature, The 400 Blows (1959), was more than a semi-autobiographical film; it was also an elaboration of what the French New Wave directors would embrace as the caméra-stylo (camera as pen), whose écriture (writing style) could express the filmmaker as personally as a novelist’s pen. It is one of the supreme examples of “cinema in the first-person singular.” In telling the story of the young outcast Antoine Doinel, Truffaut was moving both backward and forward in time—recalling his own experience while forging a filmic language that would grow more sophisticated throughout the 1960s.

The 400 Blows (whose French title comes from the idiom faire les quatre cents coups—“to raise hell”) is rooted in Truffaut’s childhood. Born in Paris in 1932, he spent his first years with a wet nurse and then his grandmother, as his parents had little to do with him. When his grandmother died, he returned home, at the age of eight. An only child whose mother insisted that he make himself silent and invisible, he took refuge in reading and later in the cinema.

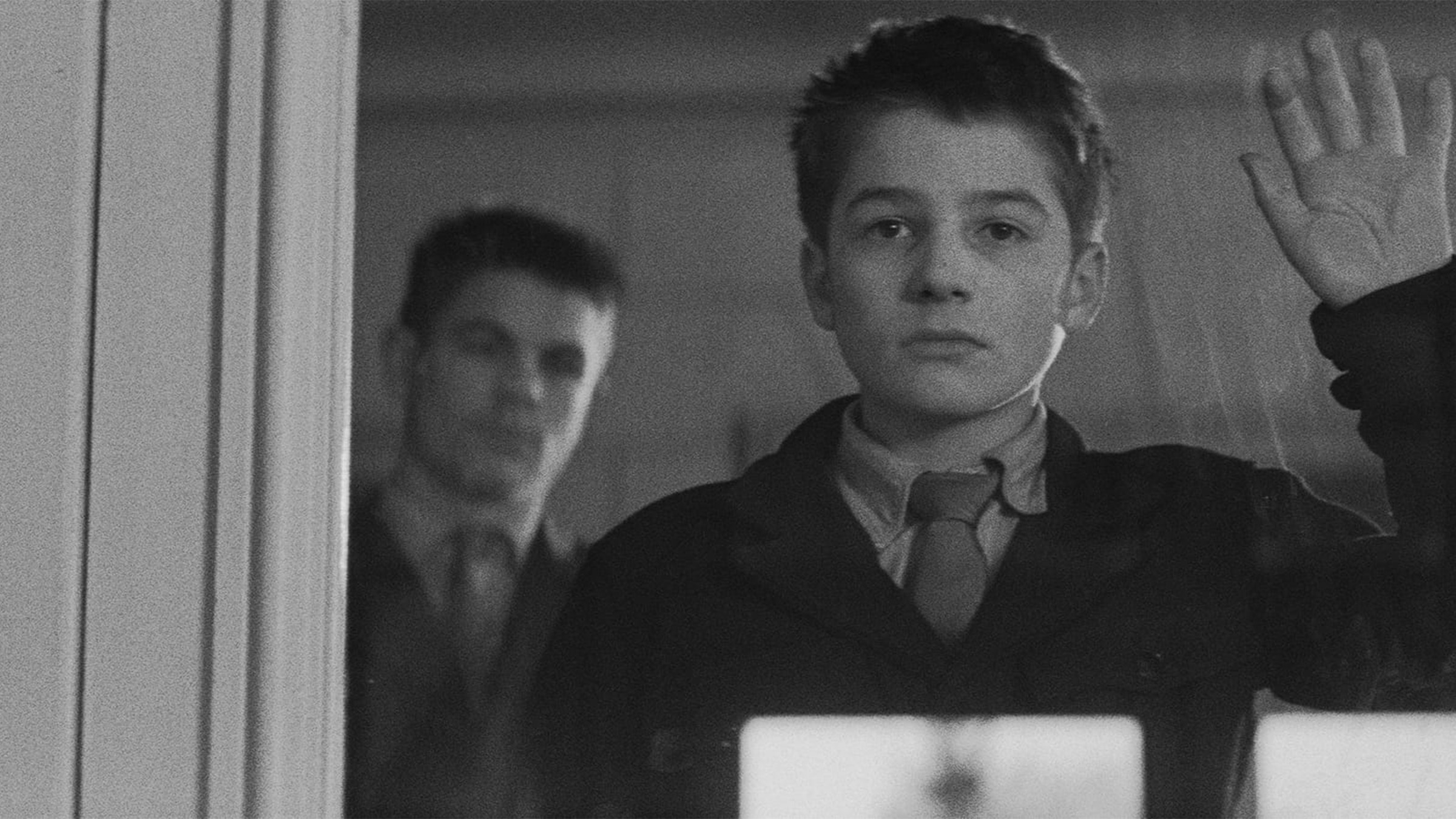

Like Antoine, Truffaut found a substitute home in the movie theater: he would either sneak in through the exit doors and lavatory windows or steal money to pay for a seat. In The 400 Blows, Antoine and René reenact the delinquency and cinemania of the young Truffaut and Robert Lachenay (who was an assistant on the film). Their touching friendship is captured in René’s unsuccessful attempt to visit Antoine at reform school.

And like Antoine, Truffaut ran away from home at the age of eleven, after inventing an outrageous excuse for his hooky-playing. Instead of Antoine’s lie about his mother’s death, Truffaut told the teacher that his father had been arrested by the Germans. The recent revelation that Truffaut’s biological father—whom he never knew—was a Jewish dentist renders this excuse especially poignant. Truffaut’s mother was only seventeen when Truffaut was born; at eighteen, she met Roland Truffaut, whom she married in 1933, and he recognized the boy as his own. Antoine’s uneasy relationship with his adoptive father reflects that of the director. After young François himself committed minor robberies, the senior Truffaut turned him over to the police.

It is not surprising that one of the dominant, although subtle, motifs throughout Truffaut’s work is paternity (nor that his entire career is marked by filial devotion to mentors like Jean Renoir and Alfred Hitchcock). In The 400 Blows, the class in English pronunciation revolves around a question that can be articulated only with difficulty: “Where is the father?”—a phrase that resonates both within the film (Antoine has never known his real father) and in the director’s life.

Antoine Doinel became a composite of two compelling individuals: Truffaut and the actor Jean-Pierre Léaud. Out of sixty boys who responded to an ad, the director chose the fourteen-year-old Léaud because “he desperately wanted that role . . . an antisocial loner . . . on the brink of rebellion.” He encouraged the boy to use his own words rather than stick to the script. The result fulfilled Truffaut’s avowed aim, “not to depict adolescence from the usual viewpoint of sentimental nostalgia but . . . to show it as the painful experience it is.”

Anticipating Truffaut’s later preoccupation with the emotional nuances of libidinal love, The 400 Blows is also a tale of sexual awakening: we see Antoine at his mother’s vanity table, toying with her perfume and eyelash curler; later he is fascinated by her legs as she removes her stockings. The stormy relationship of Antoine’s parents—a constant drama of infidelity, resentment, and reconciliation—foreshadows the romantic and marital tribulations of Antoine himself throughout the Doinel cycle and offers compelling clues to decode the male protagonists of Truffaut’s films in general.

The last shot has been justly celebrated for its ambiguity. This brief but haunting release from the harrowing experiences that fill the movie brings Truffaut’s surrogate self in direct contact with his audience—an intimacy he was to pursue throughout his career. Truffaut’s zoom in to freeze-frame (more arresting in 1959, before this technique became a stock-in-trade of television commercials) provides a mirror image of an earlier shot in the police station. When Antoine is arrested for stealing a typewriter, he is fingerprinted and photographed for the files. The mug shot is in fact a freeze-frame that conveys the definitive and permanent way in which he has been caught.

That The 400 Blows is a record—even an exorcism—of personal experience is first alluded to in Antoine’s scribbling of self-justifying doggerel on the wall while being punished. On a larger scale, we can see the film as Truffaut’s poetic mark on the wall, or his attempt to even the score. In the last scene, the sea washes away Antoine’s footprints as the film “cleans the slate”—although that final image remains indelible.

This essay was originally published in the Criterion Collection’s 2003 edition of The Adventures of Antoine Doinel.