Couple Behind the Curtain: A Conversation with Daniel Raim

The magic of the movies depends on a suspension of disbelief, and behind each great film are the countless artists and craftspeople who have trained their talents on transporting us to another world. Director Daniel Raim has spent almost twenty years throwing a spotlight on these unsung heroes, first in his Oscar-nominated documentary short The Man on Lincoln’s Nose, a portrait of Hitchcock production designer Robert Boyle, and most recently in Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story, an eye-opening chronicle of the creative partnership and marriage of two industry veterans.

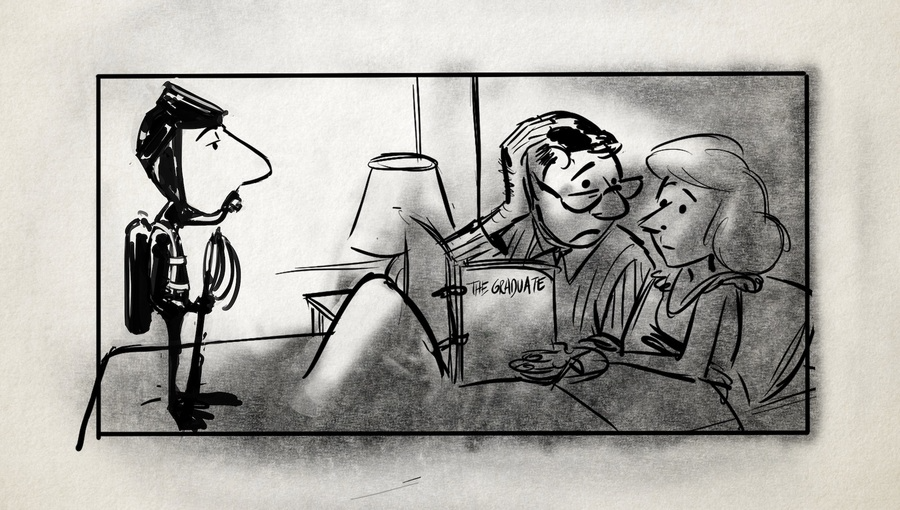

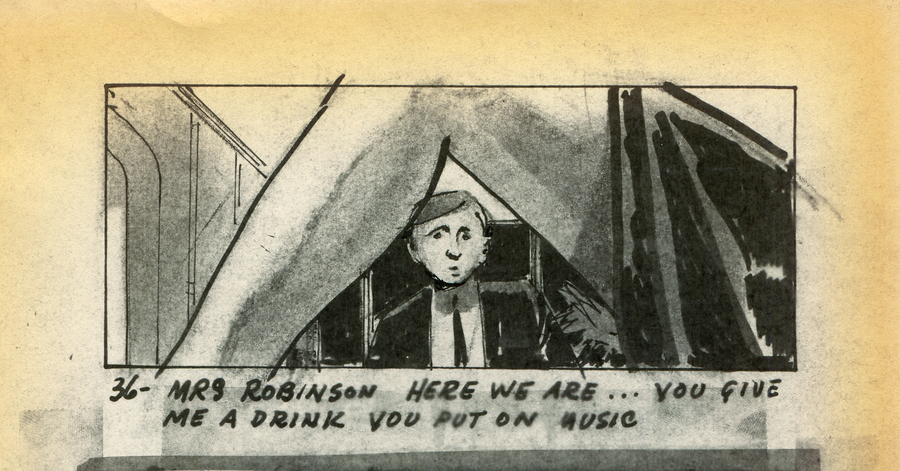

Frequently uncredited for their work, storyboard artist Harold Michelson and researcher Lillian Michelson have long stood in the shadows of their celebrated collaborators, including Alfred Hitchcock, Mike Nichols, and Francis Ford Coppola. But their indelible mark can be seen in some of the most unforgettable moments in film history. Harold’s creative input served as the blueprint for the groundbreaking camera angles in The Birds and the iconic shot of Dustin Hoffman seen through the arch of Anne Bancroft’s leg in The Graduate, while Lillian’s exhaustive research ensured the accuracy and enhanced the visual details of films like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Fiddler on the Roof, and Full Metal Jacket.

Raim’s documentary, which premiered at Cannes in 2015, combines candid interviews with film clips, heartwarming readings from the couple’s love letters, and storyboard illustrations that bring their six decades in the movie business to vivid new life. With the film opening at New York’s Quad cinema this Friday, I spoke with Raim on the phone about how he first became enamored with this power couple and what the process of making the movie taught him about the Golden Age of Hollywood.

How did you first become acquainted with Harold and Lillian’s work?

I was a student at the American Film Institute in 1997 and first became aware of Harold when my professor Robert Boyle, production designer on North by Northwest and The Birds, invited him to teach his pre-digital storyboarding technique in one of the AFI classes. So I first met him through this very dry exercise called “Camera Angle Projection.” Harold confounded us with his detailed knowledge of drawing storyboards that establish what the camera, fitted with a particular lens, sees in any given shot. This was a technique he learned in the late 1940s at Columbia Pictures. It was only later that I saw his storyboards and became aware of his genius. In 1998, I started making a documentary about Robert Boyle, and I filmed Harold, Robert, and Lillian visiting the location where The Birds had been shot thirty-seven years earlier.

Harold and Lillian would have these lunches at DreamWorks Animation, where Lillian had her research library at the time, which was full of books and clippings, and they’d invite all these different people to meet each other. I was really moved by this experience and enjoyed spending time with them and hearing about Harold’s work. He had an office next to Lillian’s library, and his bookshelf had all these original storyboards from The Cotton Club, The Ten Commandments, The Birds, Cleopatra. I was so in awe. He would love showing me his storyboards and talking about them with me. That’s how I got to experience the very nurturing, warm side of Harold and Lillian, and how I got to know them beyond their work, as just two awesome people.

Harold passed away in 2007, so in June 2013 I told Lillian that I’d like to make two short films: one about her work and the library, and one that showcased Harold’s contribution to cinema. But when I started the interview process, everyone I talked to mentioned that Harold and Lillian were inseparable. So I knew I had to rethink this whole project, but I didn’t know too much about their personal history together, and Lillian was very secretive about her childhood. On top of that, I’d never met two more camera-shy people in my life. She wouldn’t talk about anything personal, so I called her and told her I’d like to come over by myself, bring my camera, and just talk with her about life like we always did. She agreed, and that’s what went on for eighteen months.

Basically, I edited and constructed the story at the same time that I was going deeper and deeper into their lives. What ultimately gave her the confidence to share some of the unflattering stuff was knowing that I didn’t want to make a hagiography about them, and I didn’t want the audience to think that we were putting Harold on a pedestal. In order to tell their story authentically, I needed to humanize Harold and ask her to talk about some of the more difficult experiences they went through.

How did you go about poring over decades’ worth of storyboards, footage, and other materials?

At first it was all over the place. There were materials everywhere, and it was really an intense process. The most interesting source was a filmmaker named Daniel Fisher, who in 1992 was a student at UCLA and had filmed this amazing archival footage of Lillian at her research library at Paramount Studios. We had a fifth-generation cassette of the footage with a huge time code stamp, and it was unusable. I spent months trying to track down the filmmaker who shot it to try to get the masters, but we couldn’t find the guy, and finally Lillian called her friend, who’s a detective, and within literally two minutes I got a phone call from this detective, who gave me Daniel Fisher’s name and email. It took him about a month, but he found those master tapes in a shoebox in a friend’s apartment. For me, that was such a turning point, because it was one thing to have Lillian talk about her life’s work, but to actually see her on the floor collecting books and materials was really fundamental to piecing the film together. Then the challenge became how to figure out a way to visualize this love story without any records and with so few home movies and family photos.

Patrick Mate was one of the oddball characters I met at the DreamWorks lunches twenty years ago; he was a senior animator there. I was in awe of him, and it was a dream of mine to work with him on this film. I managed to get him to see a rough cut, and he said he would love to work with me on visualizing the story of Harold and Lillian. At the time, I was open to what the actual technique would be, and he suggested we do storyboards in Harold’s style. I thought that would be great and would integrate organically with the story. The initial idea developed into these storyboard-esque illustrations that underscore a lot of the thematic nuance of the movie and capture Harold and Lillian’s charm and wit.

One of the reasons I wanted to make this film was to get inside Harold’s mind and understand the cinema literacy and film grammar he learned from Alfred Hitchcock and other directors and how that was translated into storyboards. Some film critics feel like Hitchcock pushed the envelope of film grammar with The Birds, in terms of blurring subjective and objective points of view, and Harold spent three years with Hitchcock during the making of The Birds and Marnie, learning his specific way of telling stories.

It was the Graduate storyboards that really blew it open for me. This was the first time Harold was working on the visual approach mostly without the guidance of the director. This was Mike Nichols’s second film, and though he was a master Broadway director and a master of working with actors, he gave Harold carte blanche for about a year to develop the visualization of The Graduate. We were lucky to have archival footage of Harold on camera talking us through his creative process. One of the sequences I’m most in awe of is the hotel sequence in that film. It’s so beautiful to see how he constructs these scenes visually and makes them so rich.

To think that he had started The Graduate right at the same time that he’d just completed The Birds and Marnie. It was all within the same seven years. Not only was he a brilliant storyboard artist, he was also really fortunate that Robert Surtees was the cinematographer on The Graduate, because Surtees loved Harold’s storyboards. If Haskell Wexler, one of my mentors, had been the cameraman on The Graduate, I don’t think he would have been using Harold’s storyboards, quite frankly.

There absolutely is. Harold talked a lot about how he’d spend a year or more doing the storyboards on a movie, and then the cinematographer would be hired a month or two before shooting and his work would often go out the window. My understanding is that, in general, cinematographers want a certain freedom to come up with the shots and the angles. But it’s fascinating to think that Harold, because of his technical training in the studio system, was able to indicate in the storyboards the lens and the height and tilt of the camera. Everything was so thoroughly thought-through that Hitchcock’s cinematographer could literally take Harold’s storyboards and set up the shot without even thinking about it too much. If you do a side-by-side for every shot in The Birds, Harold’s storyboards are pretty consistent with what they actually filmed.

Hitchcock had the luxury, long before the script was written, of gathering his key artists and collaborators around a table for meetings in his bungalow at Universal Studios. That would include Harold, Robert Boyle, cinematographer Robert Burks, matte painter Albert Whitlock, editor George Tomasini, the screenwriter, and maybe the costume designer, and they would all be in a room while Hitchcock talked about the sequences in his mind. Harold and Robert would make these thumbnail sketches, and what Harold was ultimately able to do was enhance Hitchcock’s vision and translate it into a series of continuity sketches that told the story in a way that ultimately became what we see on-screen.

This is all to say that Harold should be recognized as one of the greatest cinema minds of the twentieth century, and the fact that he didn’t even get credit on The Birds, Marnie, or The Graduate needs to give way to a new understanding of how these films were made. But I should say that Harold and Lillian never sought the spotlight. That’s why I think the movie works, because I myself am setting out to set the record straight—to understand who they were, what their contributions were, and why they were so brilliant.

That was a discovery for me, and getting researcher and producer Anahid Nazarian on camera was a challenge too. She saw a rough cut and agreed to be interviewed, but she’s so vital to the story because what she’s become is such a testimony to Lillian’s nurturing and taking young people under her wing. People like Tom Waits hanging out in Lillian’s library—I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s how he found some time to unwind, just drinking tea there. Part of Lillian’s brilliance is her social skills and her ability to bring people together who normally wouldn’t ever meet each other.

Did Harold or Lillian have a film that they loved to talk about most?

Lillian said that she loved working on Fiddler on the Roof. I think just from a research standpoint, she had a great time learning about the old shtetl life and all the details that needed to be researched to go into that film. She also loved working on Chinatown, and her contribution was significant to the development of the screenplay. Harold loved collaborating with Robert Boyle and Albert Whitlock on the Hitchcock pictures. I think those were some of his best times. I was also surprised and happy when I was interviewing Mel Brooks to hear him give Harold a lot of credit, including the idea for the storm troopers in Spaceballs to wear giant white balls on their heads. Mel Brooks told me, “Nobody knows about the little goodies that Harold Michelson could give you and make you look like a great filmmaker.”

Photos courtesy of Daniel Raim, Adama Films, and Zeitgeist Films.