Olmi understood the importance of this project and spent years writing and developing it. He was able to carefully shepherd his vision because he was practically a one-man film crew, handling the cinematography and editing himself, as well as coaxing the natural performances he wanted out of an entirely nonprofessional cast. Against the prevailing custom of the time that dictated shooting in easily comprehensible Italian for both cinema and television, he insisted to his producers on the use of the authentic regional dialect of Bergamasque, which requires subtitles even for Italian viewers. Originally made as a three-part miniseries for the public broadcaster Rai TV (which explains its television-friendly aspect ratio of 1.37:1), the film was released theatrically after winning the Palme d’Or in Cannes in 1978. It went on to win all the major Italian film prizes that year, as well as the National Board of Review and New York Film Critics Circle awards for best foreign-language film.

Born in the Lombard province Bergamo to a working-class family with deep Catholic roots, Olmi has almost always made work that is grounded in a strong sense of the place he comes from. For most of his life, he has lived in self-imposed isolation in the Dolomites high on the Asiago plateau, choosing to work independently, outside the politics of Italian film culture. In 1982, fresh from the success of The Tree of Wooden Clogs, he founded Ipotesi Cinema, a utopian film school and collective laboratory that still draws students to the mountain town of Bassano del Grappa to immerse themselves in creative screenwriting, directing, cinematography, and editing. Many, including Francesca Archibugi, Giacomo Campiotti, Markus Imhof, Piergiorgio Gay, and Maurizio Zaccaro, have gone on to become noted directors.

Ever since he first picked up a camera, Olmi has made observation a moral principle. He began his career in the fifties, shooting short industrial documentaries for Edison Volta, the energy company where his mother worked. These early films reveal how intimately familiar Olmi was with working-class life at that time. His first fiction work, the fresh and original Time Stood Still (1959), began as a feature-length documentary about the guards Edison stationed at its big mountain dams. Time loses its workaday connotations up in the mountains, where it’s just man and nature, as immortalized in the image of a boy playfully tossing himself into a heavy snowdrift and leaving cookie-cutter outlines in the snow.

Olmi’s next two black-and-white features draw further away from his documentary origins toward a more narrative style of storytelling. The subtly observed Il posto (1961), about a young boy’s first steps in the business world, foretells the inhuman new world about to be ushered in by the economic boom of the sixties, while I fidanzati (1962), set in a steel mill in Sicily, captures the spirit of transformation that was shaking the country as it walked the path to industrialization.

These films offer an implicit critique of the working world that would come to the fore in The Tree of Wooden Clogs. Viewed today, the film is so gravely critical of the ruling class of landowners that it is hard to believe it was reviled by some critics at the time of its release as a defense of feudalism, a sort of Catholic-populist vision idealizing resigned humility in the face of oppressive power. And it’s true that the family and the church are uncontested seats of moral values in Tree. The film’s great and undeniable religious intensity was considered reactionary and mystifying by some left-wing critics, who accused Olmi of being an enemy of modernity and an apologist for an unchanging natural world.

Olmi’s critics could hardly help comparing it with an important film that had come out just two years earlier: Bernardo Bertolucci’s Marxist epic 1900. Also taking as its subject the rigors of peasant life, this time in the Emilia-Romagna region, that film chronicles the birth of the class struggle between those who worked the land and those who harvested the profits of their labors. The two films are fascinating as companion pieces, creating a dizzying contrast between Bertolucci’s ambitious essay on Italy’s social, political, and cultural history and Olmi’s humble realism fraught with miracles.

It is, however, the latter that leaves the audience shaking with indignation over the injustice of the peasants’ plight. Surprisingly, maybe, given the film’s stripped-down simplicity, time has been kinder to The Tree of Wooden Clogs. The quiet pleasure of watching the deliberate pace of the farming seasons is interrupted by sudden epiphanies and bursts of emotion. Though far less dramatic and eventful than 1900, it is never a dull watch, and the absence of obvious lighting, production design, and stars contributes to its timeless quality. Whereas Bertolucci gives his padroni the familiar faces of Robert De Niro and Dominique Sanda, in Tree we barely glimpse the man who holds the power of life and death over these children of the earth. Olmi’s only comment on the landowner and his family is to associate them with the well-heeled culture of opera and chamber music. The peasants, instead, are identified with the sublime music of Johann Sebastian Bach, heard repeatedly on the soundtrack, until Bach’s baroque harmonies provide a spiritual metaphor akin to the ones in the films of Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson, a sort of divine blessing from above.

The opening hour rolls by on the sheer beauty of the shots, full of simplicity and quietude. We watch the peasants and their children going about their work in the fields, swapping stories, singing songs, killing a goose, butchering a hog, husking corn, washing clothes in the river while babies wail in the background. Returning to the documentary techniques he used to such great effect in his early work, Olmi virtually eliminates characters and dialogue in the early scenes. His camera darts among four families who are little better than serfs as they till the landowner’s fields and raise his livestock. Brisk cutting and an initial lack of close-ups keep the farmers from emerging as individuals until the film is well advanced: they are literally part of the landscape. Olmi is at pains to emphasize their closeness to nature—the starry sky, snow, rain, animals, growing things, the earth, and the changing seasons. Even love is part of a natural cycle, and the boy Stefano’s chaste courtship of Maddalena takes place on the road, in the midst of nature. When he asks for a kiss, she tells him, eyes lowered, that they must “wait for the right time.”

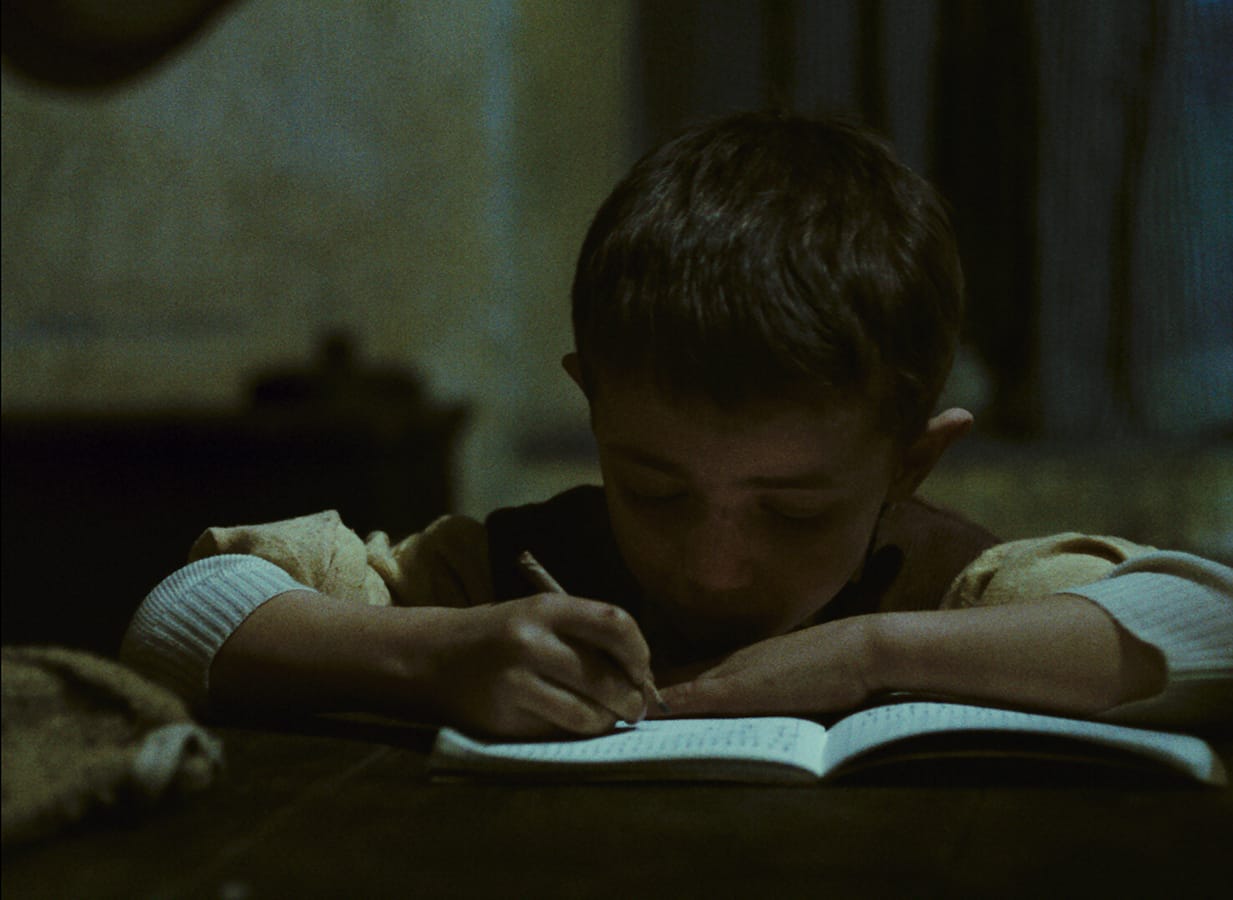

Yet the drama that will eventually shake the small community to the core is seeded in the very first scene, when the Catholic priest from town tells little Minek’s father, Batistì (Luigi Ornaghi), that his son is bright and should attend school. Though it’s four miles from the farm, Minek (played by the tiny, twinkling Omar Brignoli) has good legs and can walk. Still, it’s a major sacrifice for the family. Batistì is visibly worried about the cost of losing a hand, especially with his wife pregnant with their third child, but bows to Father Carlo’s superior wisdom. A crisis arises when Minek later breaks a sandal beyond repair, and his loving, resourceful father surreptitiously carves him a new pair of clogs out of wood from a tree that is not his own.

Another family we feel very close to belongs to the widow Runk, played with careworn sobriety by Teresa Brescianini. Her husband has died recently, leaving her alone to provide for six small children and Grandpa Anselmo, warmly played as a storyteller and agricultural innovator by Giuseppe Brignoli. She works her hands to the bone doing laundry for the landowner, but it’s never enough. When the family’s only cow gets sick, it looks like curtains. And the stakes are terribly high: if she can’t make ends meet, she will have to send her two youngest girls to an orphanage.

In every crisis, she snatches a few minutes to pray for help, and it always comes. Olmi would return to the theme of divine Providence ten years later in another famous film, The Legend of the Holy Drinker, starring Rutger Hauer as a devout but weak-willed vagabond in Paris who seeks to repay his debt of 200 francs to Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. This captivating fable, which won the Golden Lion in Venice, has many of the same emotional contact points as The Tree of Wooden Clogs: the anguish of poverty, the helplessness of outsiders and the oppressed, and the assurance that a benign force exists in the universe that will always come to the aid of those who have faith. The holy drinker is as much a beneficiary of this force as the widow Runk and her neighbors, who recite the rosary together every evening after enjoying a good round of ghost stories.