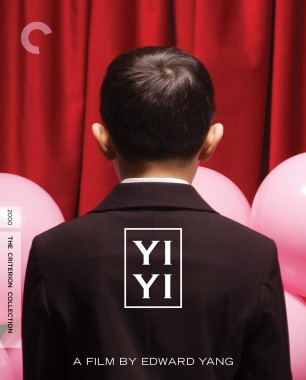

Yi Yi: Time and Space

Near the end of Edward Yang’s unjustly maligned 1996 film Mahjong, a teenage boy is humiliated by a group of older women, and he starts to cry. Yang quietly cuts to a vista of Taipei, and the boy’s sobbing merges with the night. A city of sadness indeed.

This strategy—call it poetic overlapping—is repeated many times throughout Yi Yi (2000). The laughter of one scene mingles with the cries from another, a middle-aged man’s recounting of his romantic past is intercut with his daughter’s wary excursion into first love, the sounds of rain and thunder on the soundtrack of an audiovisual presentation on the origins of life in the universe (during which a little boy feels the first stirrings of physical attraction) blend into real rain and thunder on a street corner, where the quietly nervous daughter stands under a white umbrella. There is also a great deal of visual overlapping. Again and again, foreground is counterpointed or complemented by background (or vice versa), and shades are drawn or lifted, or a door is opened or closed, to reveal the reflected cityscape, which colors, envelops, or shades the action. In Yang’s cinema in general, and in Yi Yi in particular, character and environment are inseparable.

Though they are far from interchangeable. Many filmmakers, confronted with the immensely difficult task of justly rendering urban existence, get people and place all mixed up, to the point where they become one monolithically alienating entity. Not so Yang, who, with his two great countrymen Hou Hsiao-hsien and Tsai Ming-liang, and Wong Kar Wai of Hong Kong, is a great city filmmaker. They have each thought carefully about what it’s like to live in a city, how it affects your sense of space and time, your consciousness. But I’m not sure that any of them has rendered city living with such wondrous clarity as Yang does in Yi Yi.

Following such earlier peaks as Hou’s The Puppetmaster (1993) and Flowers of Shanghai (1998), Tsai’s The River (1997), and Yang’s own remarkable “period epic” A Brighter Summer Day (1991), Yi Yi represents the apotheosis of the new Taiwanese cinema in general, which began in the early eighties in a spirit of youthful solidarity. A chorus of artists reflected with newfound freedom on thirty-nine years of martial law and a country caught in the crunch between a succession of dominant cultures (Japan, China, the United States), its collective sense of historical perspective disappearing in the shadows of ramped-up consumerism almost as quickly as it was emerging from the darker shadows of political repression. Although this creative surge produced some remarkable films made in rural settings—Hou’s A Summer at Grandpa’s (1984) and Dust in the Wind (1986), Lin Cheng-sheng’s A Drifting Life (1996)—the New Taiwan Cinema was a predominantly urban phenomenon, the better to dramatize the rapacious speed of cultural upheaval. And Yang, Hou, and the slightly younger, Malaysian-born Tsai have employed, each in his own unique way, the sights, textures, rhythms, and social configurations of city living to devastating effect. The third section of Hou’s recent Three Times (2005) and his Tokyo film Café Lumière (2003), Tsai’s overall body of work, and the majority of Yang’s films are poetically acute, pocket-size “city symphonies,” separately and together comprising one of the brightest features of modern cinema. And Yi Yi may be the most exquisitely refined of them all.

My first impressions of Yi Yi were general ones, of visual beauty, narrative complexity, and quietude. Since I was familiar with Yang’s previous work, the complexity, and particularly the beauty, came as no surprise. Few modern filmmakers use the frame so precisely, with such a firm grasp of all its expressive properties—light and color but also scale, proportion, distance, containment, concealment. Among its many other qualities, Yang’s is a cinema of luminosity, his painterly eye dedicated to getting the exact tone of city life. A teenage couple standing beneath an overpass, slowly working their way toward a first, tentative kiss as the traffic light in the distance goes from red to green and back to red—this seemed like vintage Yang, at a heightened level of creativity and confidence. It was the quietude that seemed new. At first glance, Yi Yi appears to be a serene and becalmed film, in pace and spirit, a movie made by a director who has shed his youthful anger and made peace with the assorted confusions of “late capitalist” Taiwanese life. On close scrutiny, it becomes something else again. Yang has set his city symphonies in a variety of emotional keys—the doleful lament of Taipei Story (1985), the gridlike coolness of The Terrorizers (1986), the comic hysteria of A Confucian Confusion (1994), the carefully modulated fury of Mahjong. In Yi Yi, he brings all of these moods together, never allowing any one of them to take precedence over another. Which is to say that this is a grand choral work, with a panoptic majesty and an emotional amplitude worthy of George Eliot or late Beethoven, whose “Song of Joy” is quoted with the greatest delicacy in Kaili Peng’s piano score.

Like many other films that shuffle their focus among a set of interrelated characters, Yi Yi is structured around rituals—a wedding, a funeral, a birth, departures and homecomings, rites of passage and realizations (there is also, somewhat less convincingly but forcefully nonetheless, a murder). And yet, this is very far from another “. . . and life goes on” movie. One feels the presence of what we call life, all right, with its cyclical repetitions and its greater mysteries, but Yang also touches on something quite unusual here, an insight so refined and subtle that it should leave most modern filmmakers and fiction writers green with envy.

There are many clichés of what we refer to as “modern life”—in fact, the term itself is a cliché. There is no sense of continuity . . . Everywhere looks the same as everywhere else . . . We suffer from information overload . . . We have lost our connection to the rhythms of the natural world . . . etc. and ad infinitum. One might say that such maxims, which hang in the air like storm clouds just before a downpour, indicate one of the most serious maledictions of the modern condition. Of course, there is truth to many of these notions, but the alarm bells they set off in our heads drown out our ability to think them through. For instance, are these changes permanent or temporary? To what extent must we adapt to them, and to what extent must we find a way of making them adapt to us? And what exactly has changed, and what exactly has stayed the same? These are reasonable, human questions, questions whose answers can’t be found in others—lost loves, for example, or spiritual gurus or astrologists, all of whom the various characters in Yi Yi turn to throughout the film. They can be answered only by us, the ones who are posing them. In time. “We all need time to think,” exclaims Wu Nien-jen’s NJ, with carefully concealed desperation. So Yang—so patient, so attentive, so precise—gives each of his characters, and us, too, time to think. He shows us that the time must and will come, and that the thinking will follow, and that the “impersonality” of urban existence (another cliché) is a state of mind: any given street corner, New York bagel shop, hotel room, or corridor is personalized just by the presence of living, thinking, feeling human beings. Personalized and illuminated—which is why Yang’s luminosity is so quietly stirring here.

Throughout the film, we are presented with visions of characters alone in the frame, simply existing within pockets of time; one might say that Yi Yi is made up of a succession of Ozu’s “pillow shots,” but with people in them. Emotional conflicts are rarely talked through until they’ve reached a crisis level; people are either too embarrassed or too awkward or too angry to confront one another or share their problems. Sound familiar? Everyone here exists within his or her own proper space on the mental grid, modeled from the grid of lighted offices on the Taipei skyline and measured in units that are at once spatial, social, and, maybe, spiritual. Nearly everyone in Yi Yi acts rashly and impulsively, and everyone is essentially alone. NJ, for instance, may be the “good man” that Issey Ogata’s Mr. Ota claims he is, and he may be the kind of father to his son that he wishes he’d had (“a friend”), but he is also preoccupied and benignly distant. And yet Yang shows us, with the greatest delicacy, that all these loose threads do indeed make a fabric. NJ may be far away in Japan with his old lover Sherry (Ke Su-yun), but he is in a kind of temperamental harmony with his daughter, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), as she goes on her first date. And Jonathan Chang’s eight-year-old Yang-Yang may be left to his own devices, but he is also as carefully observant of the world around him as his father, as we learn when he presents his crazy uncle with a photo of the back of his head (“You can’t see it yourself, so I’m helping you”) or when he finally finds his voice and speaks the film’s final words.

Of course, Yi Yi would be nothing without its extraordinary ensemble. There is something moving about the way that Yang and his actors work together, the way they locate stillnesses and rest points and surges, the way every emotional gradation is so carefully calibrated. How to pinpoint the precise, lifelike humility of Wu as NJ, as he quietly observes the fracas between his brother-in-law’s new wife and old girlfriend, or as he pauses before he knocks on Sherry’s hotel-room door? The part was written for Wu, a onetime writing partner of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s, a Taiwanese TV star, and a formidable filmmaker in his own right (he directed the heart-wrenching A Borrowed Life, 1994), and his quiet, thoughtful presence both animates and anchors the movie. How to do justice to the fawnlike beauty and reticence of Lee as Ting-Ting, or to Chang’s nearly affectation-free acting as the silently inquisitive Yang-Yang? Or to the magical presence of the great Ogata’s Ota, whose every word and gesture sparkles like a diamond?

Yi Yi is ultimately a film that imparts its meaning and its impact through its exquisite sense of balance—between here and elsewhere, past and present, the ideal and the conditional, the mundane and the extraordinary. It is a film of, and about, grace. And that is a rare thing.

This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2006 edition of Yi Yi